-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaCauses of Acute Hospitalization in Adolescence: Burden and Spectrum of HIV-Related Morbidity in a Country with an Early-Onset and Severe HIV Epidemic: A Prospective Survey

Background:

Survival to older childhood with untreated, vertically acquired HIV infection, which was previously considered extremely unusual, is increasingly well described. However, the overall impact on adolescent health in settings with high HIV seroprevalence has not previously been investigated.Methods and Findings:

Adolescents (aged 10–18 y) systematically recruited from acute admissions to the two public hospitals in Harare, Zimbabwe, answered a questionnaire and underwent standard investigations including HIV testing, with consent. Pre-set case-definitions defined cause of admission and underlying chronic conditions. Participation was 94%. 139 (46%) of 301 participants were HIV-positive (median age of diagnosis 12 y: interquartile range [IQR] 11–14 y), median CD4 count = 151; IQR 57–328 cells/µl), but only four (1.3%) were herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) positive. Age (median 13 y: IQR 11–16 y) and sex (57% male) did not differ by HIV status, but HIV-infected participants were significantly more likely to be stunted (z-score<−2 : 52% versus 23%, p<0.001), have pubertal delay (15% versus 2%, p<0.001), and be maternal orphans or have an HIV-infected mother (73% versus 17%, p<0.001). 69% of HIV-positive and 19% of HIV-negative admissions were for infections, most commonly tuberculosis and pneumonia. 84 (28%) participants had underlying heart, lung, or other chronic diseases. Case fatality rates were significantly higher for HIV-related admissions (22% versus 7%, p<0.001), and significantly associated with advanced HIV, pubertal immaturity, and chronic conditions.Conclusion:

HIV is the commonest cause of adolescent hospitalisation in Harare, mainly due to adult-spectrum opportunistic infections plus a high burden of chronic complications of paediatric HIV/AIDS. Low HSV-2 prevalence and high maternal orphanhood rates provide further evidence of long-term survival following mother-to-child transmission. Better recognition of this growing phenomenon is needed to promote earlier HIV diagnosis and care.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 7(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000178

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000178Summary

Background:

Survival to older childhood with untreated, vertically acquired HIV infection, which was previously considered extremely unusual, is increasingly well described. However, the overall impact on adolescent health in settings with high HIV seroprevalence has not previously been investigated.Methods and Findings:

Adolescents (aged 10–18 y) systematically recruited from acute admissions to the two public hospitals in Harare, Zimbabwe, answered a questionnaire and underwent standard investigations including HIV testing, with consent. Pre-set case-definitions defined cause of admission and underlying chronic conditions. Participation was 94%. 139 (46%) of 301 participants were HIV-positive (median age of diagnosis 12 y: interquartile range [IQR] 11–14 y), median CD4 count = 151; IQR 57–328 cells/µl), but only four (1.3%) were herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) positive. Age (median 13 y: IQR 11–16 y) and sex (57% male) did not differ by HIV status, but HIV-infected participants were significantly more likely to be stunted (z-score<−2 : 52% versus 23%, p<0.001), have pubertal delay (15% versus 2%, p<0.001), and be maternal orphans or have an HIV-infected mother (73% versus 17%, p<0.001). 69% of HIV-positive and 19% of HIV-negative admissions were for infections, most commonly tuberculosis and pneumonia. 84 (28%) participants had underlying heart, lung, or other chronic diseases. Case fatality rates were significantly higher for HIV-related admissions (22% versus 7%, p<0.001), and significantly associated with advanced HIV, pubertal immaturity, and chronic conditions.Conclusion:

HIV is the commonest cause of adolescent hospitalisation in Harare, mainly due to adult-spectrum opportunistic infections plus a high burden of chronic complications of paediatric HIV/AIDS. Low HSV-2 prevalence and high maternal orphanhood rates provide further evidence of long-term survival following mother-to-child transmission. Better recognition of this growing phenomenon is needed to promote earlier HIV diagnosis and care.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

In industrialised countries trauma and behavioural disorders, such as substance abuse, obesity, and sexually transmitted infections account for most adolescent morbidity [1]. Chronic diseases, trauma, oncology, and mental disorders account for the majority of hospital admissions [2],[3]. In Africa, research on adolescent morbidity has been limited and has predominantly focused on reproductive health, reflecting the high incidence of sexually transmitted infections and obstetric problems among young people [4],[5].

As the HIV epidemic matures, long-term survival of HIV-infected infants to adolescence following vertical transmission is increasingly being recognised in African countries [6],[7]. Symptomatic HIV in older children and adolescents is a growing problem in clinical practice but there are few data describing the burden of HIV and its contribution to ill-health and mortality in this age group [8],[9]. In Southern Africa—the global region that has experienced the most severe adult HIV epidemic [10]—a substantial epidemic of HIV-infected long-term survivors of vertical infection is anticipated during the coming decade, with implications for adolescent health [11].

The spectrum of HIV-related disease varies considerably between adults and children, but has not been well-defined for adolescents. Although opportunistic infections predominate in all age groups, chronic noninfectious clinical conditions may be more prominent in HIV-infected adolescents than in adults and infants [9]–[12]. In clinical studies of HIV infection, children are often classified as aged 0–14 y and adults as 15–49 y, and thus distinctive features of HIV-associated morbidity among adolescents may be missed [13]–[15]. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of HIV and the spectrum of morbidity among hospitalised adolescents aged 10–18 y in Harare, Zimbabwe.

Methods

Study Participants

Harare Central Hospital and Parirenyatwa Hospital are the main public sector hospitals in Harare and cater to two-thirds of Harare's population; the remaining one-third using private health care facilities. The cost of hospitalisation in public sector facilities is partially subsidised by the government. Malaria transmission does not occur in Harare. Between September 2007 and April 2008, patients admitted to either hospital were enrolled consecutively the following day. Recruitment was limited to weekdays and to a maximum of five patients per site per day for logistical ease. Patients aged between 10 and 18 y admitted with any acute medical or surgical condition, including trauma, were eligible. Patients were excluded if moribund (i.e., likely to die within the next few hours), requiring intensive care admission, or admitted for obstetric or elective reasons, or previously enrolled into the study.

Data Collection

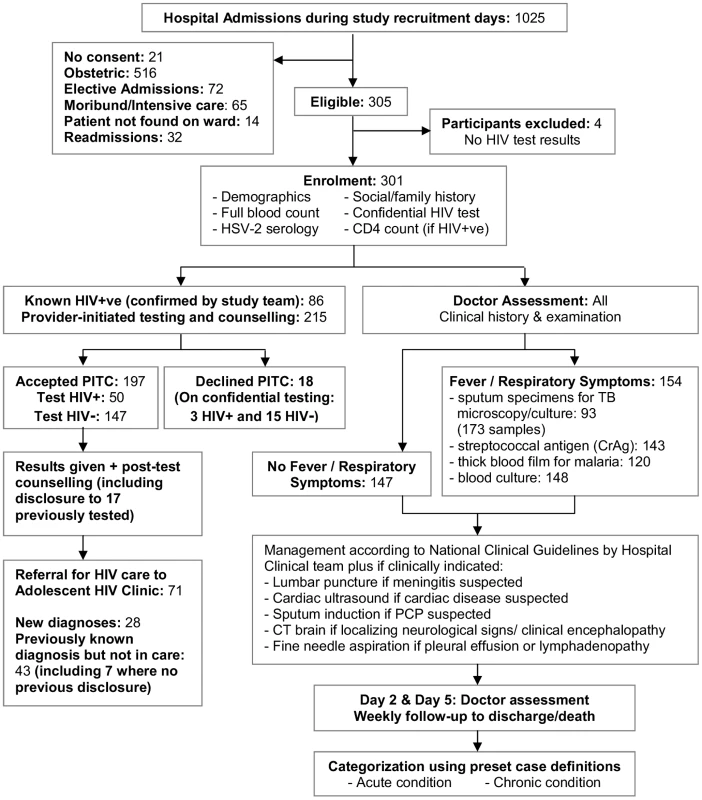

Standardised investigations, summarised in Figure 1, included social and clinical history, height, weight, and Tanner puberty staging, and laboratory investigations (full blood count, herpes simplex virus-2 [HSV-2] serology, provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling [PITC], and CD4+ lymphocyte [CD4+] count for HIV-infected participants). Where diagnostic HIV testing was declined, participants and their guardians were asked to consent to unreported HIV-testing for study purposes. In addition, all participants with febrile, wasting, or respiratory illness had a standardised infectious screen (blood culture, blood films for malaria, cryptococcal antigen testing [serum 1∶8 dilution], two sputum specimens, and chest radiography). If Pneumocystis jirovecii infection was suspected, patients underwent sputum induction with nebulised hypertonic saline.

Fig. 1. Study recruitment procedure for eligible participants.

Otherwise investigations followed standard hospital guidelines including lumbar puncture for suspected meningitis and cerebral computed tomography (CT) for focal neurological signs or suspected encephalopathy. Participants were followed for the duration of their hospital stay. Pre-set diagnostic algorithms defined the definitive or presumptive cause of admission, and any underlying chronic conditions (Text S1). The Adult World Health Organization (WHO) Classification was used to stage HIV infection [16].

Laboratory Methods

HIV serology used parallel testing with Abbott Determine and SD Bioline. Discordant samples were resolved using Vironostika. HSV-2 antibodies were detected using recombinant IgG antigen (HerpeSelect, Focus Technologies; cut-off for positivity: OD>1.1). CD4 counts were determined by flow cytometry (CyFlow counter, Partec).

Blood culture used Myco/F Lytic (MFL, Becton Dickinson) [17], inspected daily using a handheld UV Woods lamp. Bacterial pathogens were identified by Gram staining and culture on conventional media, with biochemical tests for confirmation. Concentrated decontaminated sputum specimens and positive blood cultures were examined under fluorescent microscopy (Auramine-O) and cultured for mycobacteria (Lowenstein-Jensen media). CSF and positive blood cultures were investigated for Cryptococcus using India ink contrast staining, culture on Sabouraud media, and cryptococcal antigen testing (IMMY, Alpha Laboratories). Induced sputum was stained with Grocott's silver stain. Thick blood films for malaria were examined using Giemsa staining.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed with STATA software, version 10.0 (STATA Corporation). Continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test for normally distributed variables and Mann Whitney U test for variables not normally distributed. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared (χ2) or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Z-scores for height - and weight-for-age were calculated using British 1990 Growth Reference Curves, which provide data over the age of 10 y [18]. z-Scores of <−2 were considered to represent stunting and wasting, respectively [18].

Multivariate logistic regression was used for analysis of risk factors for mortality [19]. Risk factors were considered in two groups: socio-demographic (sex, age, orphanhood, difficulty raising clinic fees, tuberculosis [TB] or illness in a household member, food shortage, type of care-giver) and clinical (stage of HIV, previous TB, antiretroviral therapy [ART] status, stunting, wasting, pubertal delay, chronic disease, anaemia, poor performance scores, self-perceived poor health, broad diagnosis category). An initial model included socio-demographic factors and all factors that reached statistical significance at p<0.05 were included in a multivariate model. Factors that remained independently associated with death were retained. The association between each factor in the clinical group and death was assessed by adding each factor into the multivariate model that included the subset of independently significant socio-demographic factors. The multivariate model was built that included the subset of socio-demographic factors in the first multivariate model plus any clinical factors that were significant after adjusting for the socio-demographic factors. The final multivariate logistic regression model was reached by excluding single factors sequentially until all remaining factors were statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

Written consent was obtained from all participants and from guardians of participants aged below 16 y. Onward referral for HIV care services was made for all testing HIV-positive. Guardians were encouraged to disclose HIV status to HIV-infected participants who did not know their status. Ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the Ethics Committees of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Joint Research Ethics Committee at the University of Zimbabwe, Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ), Harare and Parirenyatwa Hospital Ethics Committees and the Institutional Review Board of the Biomedical Research and Training Institute.

Results

Baseline Participant Characteristics and HIV Diagnosis

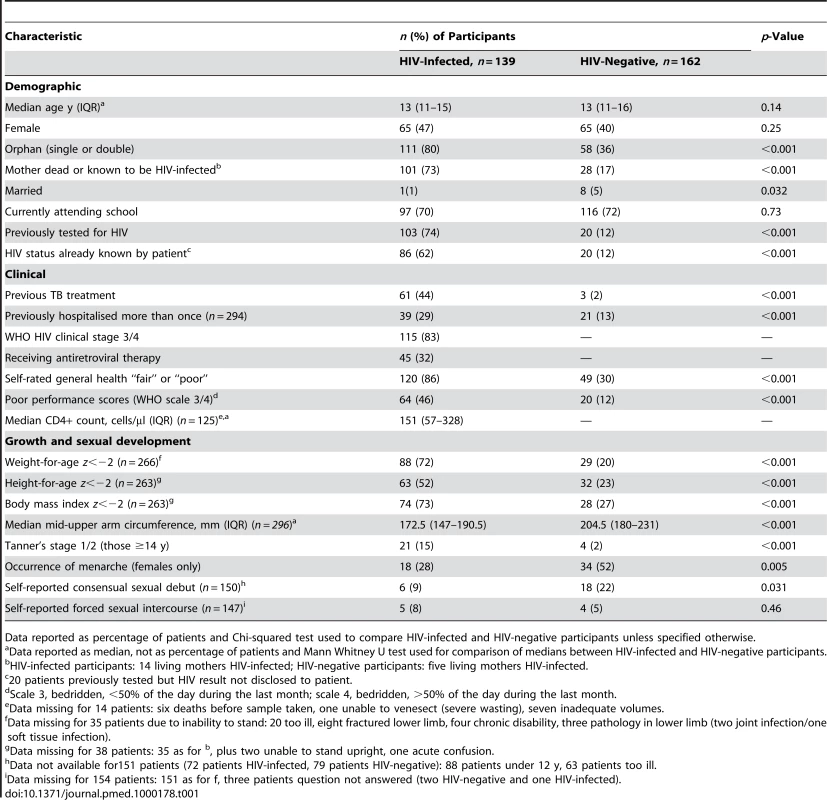

Of 1,025 total adolescent hospital admissions, 340 were eligible. 301 participants were recruited, with a refusal rate of 6% (Figure 1). HIV prevalence was 46%. The median age was 13 y (interquartile range [IQR]: 11–16), and 43% of participants were female, with no significant association of age or sex by HIV status (Table 1). Four (1.3%) participants tested HSV-2 positive, of whom two were HIV-positive. HIV-infected participants were less likely to be married (1% versus 9%, p<0.032), although the comparison was based on small numbers.

Tab. 1. Baseline demographic, clinical, and growth characteristics of adolescents admitted to hospital (n = 301 unless specified otherwise).

Data reported as percentage of patients and Chi-squared test used to compare HIV-infected and HIV-negative participants unless specified otherwise. The median age at diagnosis of HIV infection was 12 y (IQR: 11–14). Of the 139 participants who were HIV-positive, 86 (62%) had tested prior to admission and knew their HIV status. Fifty participants tested positive following PITC; of these, 17 had tested HIV-positive previously but had not been told of their HIV infection. All guardians, however, agreed to disclosure to the participant with assistance of study counsellors. Only 18 (6%) participants declined PITC, of whom three were HIV-positive on unreported HIV testing and are likely to remain unaware of their HIV infection.

HIV-infected participants were significantly more likely to be orphans, previously treated for tuberculosis, previously hospitalised more than once, stunted, and pubertally immature (Tanner's stage 1/2 for participants aged 14 y or older, and girls less likely to have undergone menarche) (Table 1).

HIV-infected patients were profoundly immunosuppressed at presentation: 83% had WHO stage 3 or 4 disease and 58% had CD4+ T lymphocyte counts <200 cells/µl. Only 44 (43%) of the HIV-infected participants who had previously had an HIV test were on ART (for a median duration of 121 d).

Causes of Hospitalisation and CD4+ Counts by Diagnostic Group

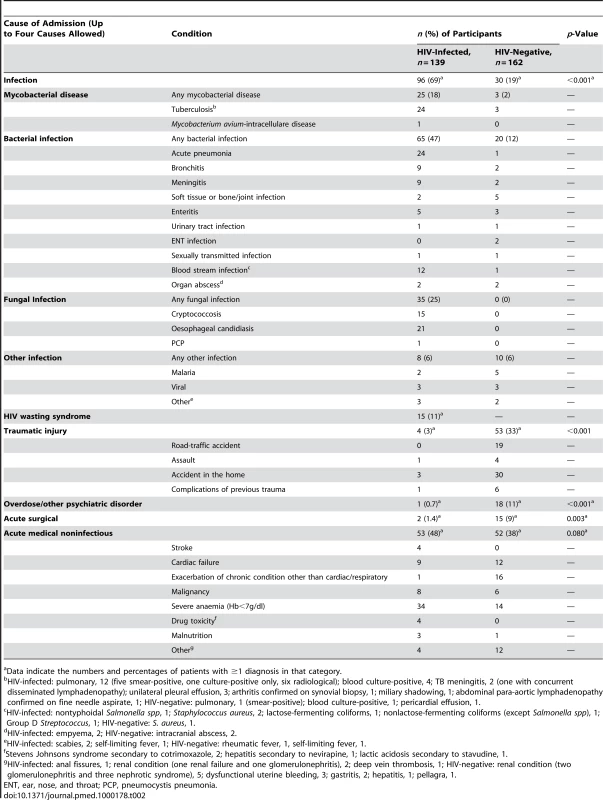

The most frequent diagnosis among HIV-infected participants was infection with tuberculosis, pneumonia, cryptococcosis, and blood stream infections being the most frequent diagnoses. Among HIV-negative participants, the commonest cause of admission was trauma, followed by acute exacerbations of chronic medical conditions, predominantly cardiac (Table 2). The median duration of stay in hospital for HIV-infected participants was 9 d (IQR 6–16 d) and for HIV-negative participants 7 d (IQR 4–18 d).

Tab. 2. Causes of admission among adolescents admitted to hospital.

Data indicate the numbers and percentages of patients with ≥1 diagnosis in that category. The highest median CD4 counts were found in patients presenting with trauma or acute surgical causes conditions (455 and 628 cells/µl). Patients with blood stream infections, oesophageal candidiasis, and HIV-wasting syndrome had the lowest median CD4 counts (85, 77, and 34 cells/µl, respectively).

Disease-Specific Microbiological Findings

113 (81%) and 41 (25%) of HIV-infected and HIV-negative admissions (p<0.001) met criteria for the standardised infectious screen (see Methods), of whom 20 (18%) and two (5%) had positive blood cultures, respectively. The most frequently identified pathogens in HIV-infected participants were nontyphoidal Salmonella species and M. tuberculosis. Cryptococcus spp. were identified in blood culture in three patients, in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture in five patients, and seven patients had a positive cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) only.

There were 27 TB diagnoses of which 13 were pulmonary TB: six were sputum smear - positive, one was culture-positive only, and six were radiological diagnoses (smear - and culture-negative pulmonary disease with failure to respond to broad-spectrum antibiotics, but response to TB treatment at 1 mo). M. tuberculosis was identified in blood culture in five patients.

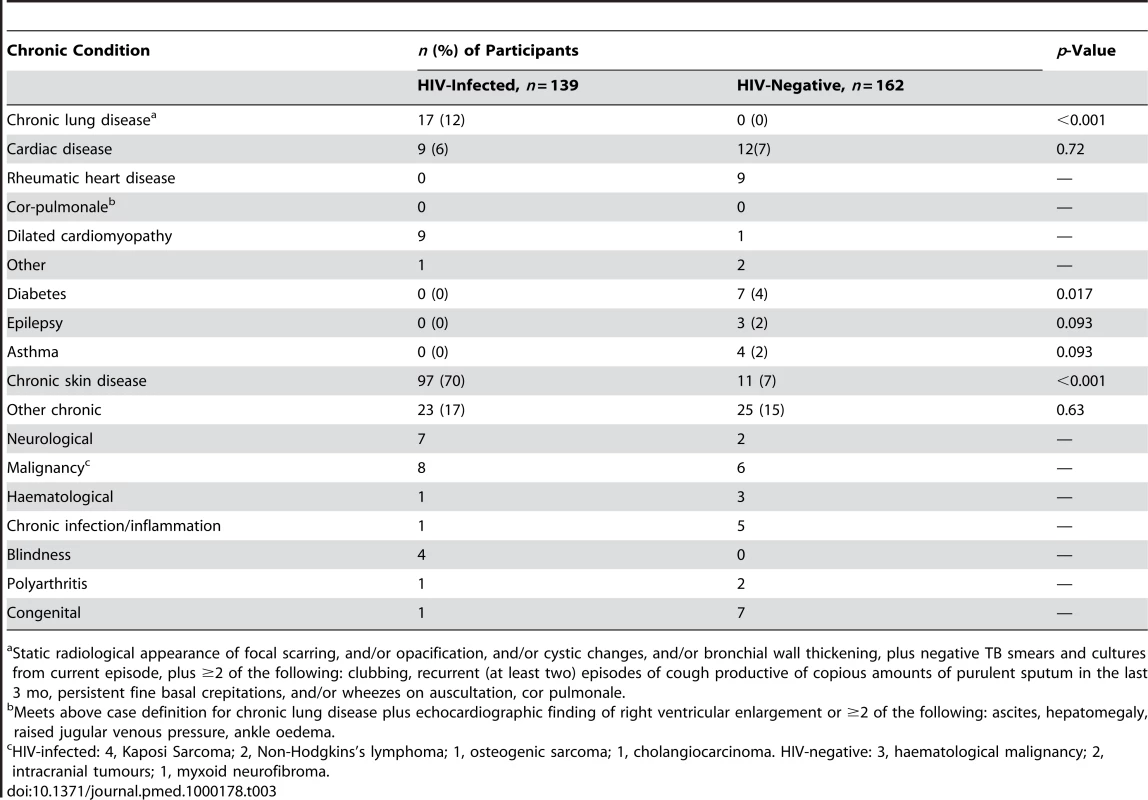

Chronic Clinical Conditions

84 (28%) participants had underlying chronic medical conditions other than HIV (26% in HIV-infected versus 29% in HIV-negative, p<0.56). In addition, 70% of HIV-infected participants had chronic skin complaints, although rarely responsible for admission (Table 3). Admission as a result of acute exacerbation of a chronic condition accounted for 26 (19%) and 44 (27%) admissions in HIV-infected and HIV-negative participants, respectively (p<0.082). Chronic lung disease and cardiac disease were the most common serious HIV-related complications (Table 3). In HIV-negative participants, rheumatic heart disease was the most common chronic condition.

Tab. 3. Chronic conditions among adolescents admitted to hospital.

Static radiological appearance of focal scarring, and/or opacification, and/or cystic changes, and/or bronchial wall thickening, plus negative TB smears and cultures from current episode, plus ≥2 of the following: clubbing, recurrent (at least two) episodes of cough productive of copious amounts of purulent sputum in the last 3 mo, persistent fine basal crepitations, and/or wheezes on auscultation, cor pulmonale. Causes of and Risk Factors for Death in Hospital

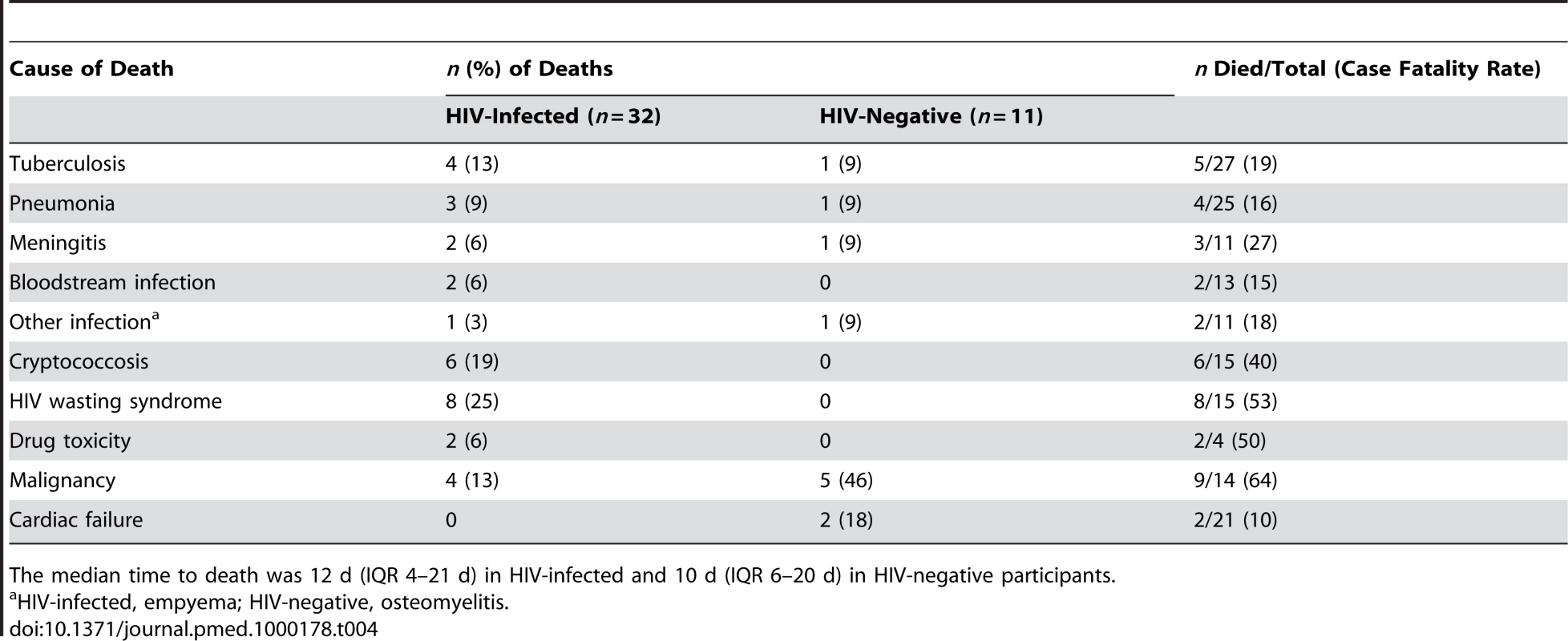

32/139 (23%) HIV-infected participants died in hospital compared with 11/162 (7%) HIV-negative participants (sex - and age-adjusted odds ratio [OR] for death for HIV-infected patients 3.7, 95% [confidence interval] CI 1.7–7.8, p<0.001). Death was significantly associated with low CD4+ T lymphocyte count (74 versus 183 cells/µl, p<0.0029). The highest case-fatality rates among HIV-infected participants were from HIV wasting syndrome (53%), any malignancy (50%), and drug toxicity (50%), and among HIV-negative participants the highest case-fatality rates were for malignancy (83%) (Table 4).

Tab. 4. Causes of death among adolescents admitted to hospital.

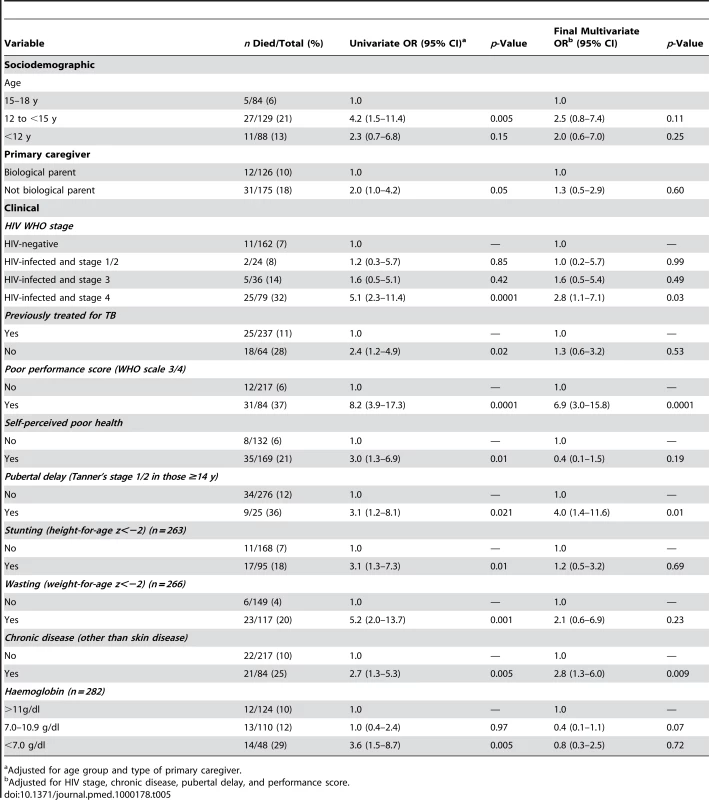

The median time to death was 12 d (IQR 4–21 d) in HIV-infected and 10 d (IQR 6–20 d) in HIV-negative participants. Of the considered socio-demographic risk factors, younger age and having a primary care-giver who was not the parent were associated with an increased risk of death (Table 5). After adjusting for these factors, advanced HIV disease, severe anaemia, TB treatment in the past, poor self-rated health, a chronic disease (except chronic skin disease), pubertal delay (Tanner puberty stage 1/2 in those aged 14 y or above), poor performance scores, wasting, and stunting were all associated with increased risk of death. In the final multivariate model, WHO stage 4 HIV infection (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.1–7.1; p<0.032), chronic disease (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.3–6.0; p<0.009), pubertal delay (OR 4.0, 95% C.I 1.4–11.6; p<0.011), and poor performance scores (OR 6.9, 95% C.I 3.0–15.8; p<0.001) remained independently associated with increased risk of death.

Tab. 5. Risk factors for death among adolescents admitted to hospital (n = 301 unless specified).

Adjusted for age group and type of primary caregiver. Discussion

The main finding of this study is that HIV is now the single most common cause of acute admission and in-hospital death among adolescents in Harare. HIV-infected adolescents were profoundly immunosuppressed, and the median CD4 count (51 cells/µl) was similar to that reported in other studies of hospitalised African adults in the pre-ART era [20],[21]. The spectrum of HIV-associated infections was also similar to that reported in African adults in the pre-ART era [15]. However, adolescents had an additional and heavy burden of chronic complications—such as growth failure and lung and cardiac disease—that have typically been reported in vertically HIV-infected children [22]–[24]. In this study, underlying chronic complications were associated with an increased risk of in-hospital death.

We found an equal sex distribution of HIV infection, low rates of self-reported sexual debut, and a much lower prevalence of HSV-2 infection than would be anticipated for sexually acquired HIV in southern Africans [25]. These findings, along with strong associations with orphanhood and the chronic complications discussed above, and negative association with marriage (given that marriage at young age increases risk of HIV for young African girls [26]), all favour long-term survival following mother-to-child transmission as the source of HIV infection in most of our participants. Also notable is the fact that Zimbabwe has had an unusually good safety record for preventing percutaneous HIV from early on in the HIV epidemic [27], and population-based HIV prevalence surveys among older children in southern Africa have documented substantial HIV prevalence rates with equal gender distribution [28],[29]. The widely held perception is that HIV progresses rapidly in HIV-infected infants with a median survival of 2 y [30], and thus survival to late childhood and adolescence with untreated HIV has been considered extremely unusual. Our study, however, demonstrates that long-term survival occurs and is now a major cause of morbidity among adolescents.

Diagnosis of HIV infection was frequently delayed in this age group until presentation with advanced HIV disease. A substantial minority had not been diagnosed with HIV before hospitalisation, and most others reported relatively recent diagnosis following a prolonged history of recurrent infections. The beneficial effects of early diagnosis and ART on reducing the risk of opportunistic infections and chronic complications, reducing mortality, and improving growth are well-recognised in children [31]. In addition to the high risk of irreversible complications, older age at diagnosis and delay in starting ART may potentially result in suboptimal immune response [32],[33] and blunted catch-up growth and pubertal development [34],[35].

Although the phenomenon of long-term survival in HIV-infected infants is well recognised in Zimbabwe, several factors unique to this age group may be creating both demand and supply-side barriers to diagnostic testing: in contrast to adults, there are no free-standing counselling and testing services for under 16-y-olds in Zimbabwe, and there are also legal barriers to testing without the permission of the legal guardian, who may be incapacitated or absent. Reluctance of guardians to disclose the true nature of the underlying illness was also apparent in that a substantial minority of our HIV-infected participants had not been told their previous test results. Clear advice to health professionals to offer PITC and to assist guardians with disclosure may improve timely diagnosis and adherence to subsequent ART [36].

Our study was hospital-based and therefore likely to be biased towards sicker patients and more severe HIV-associated complications. One of the study sites was based at a referral hospital, which may have resulted in a higher proportion of specialist diagnoses such as cancer. Both hospitals had ART clinics, but only nine (6%) of the HIV-infected participants were admitted from these. The vast majority of our participants (87%) were referred directly from primary health care clinics or through hospital casualty departments, and the only local alternatives to these two hospitals are private facilities. Our results are, therefore, likely to be representative of the pattern of acute severe morbidity and mortality in Harare. Judging by the high numbers of adolescents attending HIV care clinics throughout Zimbabwe [37], our results may also be more generally representative. Zimbabwe is unusual in having had high HIV prevalence in antenatal clinic attendees from the early 1990s [38], and so may be a few years ahead of other countries in the region with respect to the subsequent epidemic of adolescent survivors.

HIV-related morbidity and mortality, most likely reflecting long-term survival from the paediatric HIV epidemic in the 1990s, is now a major cause of adolescent morbidity and mortality in Harare. Recognition of the high burden of HIV in acutely unwell older children and adolescents is needed to stimulate earlier diagnosis and improve access to HIV care for this previously neglected age group. Our results strongly support implementation of PITC for all patients in this age group attending health facilities, ideally at the primary care as well as hospital level, so that diagnosis is made and treatment can be started before patients are critically ill.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SellsCW

BlumRW

1996 Morbidity and mortality among US adolescents: an overview of data and trends. Am J Public Health 86 513 519

2. CaflischM

AlvinP

2000 Management of adolescents in pediatric hospitals. A national survey. Arch Pediatr 7 732 737

3. RosenEU

1988 Adolescent health problems–can paediatricians in the RSA cope? S Afr Med J 73 337 339

4. ObasiAI

BaliraR

ToddJ

RossDA

ChangaluchaJ

2001 Prevalence of HIV and Chlamydia trachomatis infection in 15–19-year olds in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health 6 517 525

5. AgyeiWK

EpemaEJ

LubegaM

1992 Contraception and prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents and young adults in Uganda. Int J Epidemiol 21 981 988

6. StoverJ

WalkerN

GrasslyNC

MarstonM

2006 Projecting the demographic impact of AIDS and the number of people in need of treatment: updates to the Spectrum projection package. Sex Transm Infect 82 iii45 iii50

7. MarstonM

ZabaB

SalomonJA

BrahmbhattH

BagendaD

2005 Estimating the net effect of HIV on child mortality in African populations affected by generalized HIV epidemics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 38 219 227

8. WalkerAS

MulengaV

SinyinzaF

LishimpiK

NunnA

2006 Determinants of survival without antiretroviral therapy after infancy in HIV-1-infected Zambian children in the CHAP Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 42 637 645

9. FerrandRA

LuethyR

BwakuraF

MujuruH

MillerRF

2007 HIV infection presenting in older children and adolescents: a case series from Harare, Zimbabwe. Clin Infect Dis 44 874 878

10. UNAIDS 2008 Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic Geneva UNAIDS

11. FerrandRA

CorbettEL

WoodR

HargroveJ

NdhlovuCE

2009 AIDS among older children and adolescents in Southern Africa: projecting the time course and magnitude of the epidemic. Aids 23 2039 2046

12. ShahI

2005 Age related clinical manifestations of HIV infection in Indian children. J Trop Pediatr 51 300 303

13. BakakiP

KayitaJ

Moura MachadoJE

CoulterJB

TindyebwaD

2001 Epidemiologic and clinical features of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected Ugandan children younger than 18 months. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 28 35 42

14. BobatR

CoovadiaH

MoodleyD

CoutsoudisA

1999 Mortality in a cohort of children born to HIV-1 infected women from Durban, South Africa. S Afr Med J 89 646 648

15. GrantAD

DjomandG

SmetsP

KadioA

CoulibalyM

1997 Profound immunosuppression across the spectrum of opportunistic disease among hospitalized HIV-infected adults in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS 11 1357 1364

16. World Health Organization 2005 Interim WHO clinical staging of HIV/AIDS and HIV/AIDS case definitions for surveillance - African Region Geneva World Health Organization

17. ArchibaldLK

McDonaldLC

AddisonRM

McKnightC

ByrneT

2000 Comparison of BACTEC MYCO/F LYTIC and WAMPOLE ISOLATOR 10 (lysis-centrifugation) systems for detection of bacteremia, mycobacteremia, and fungemia in a developing country. J Clin Microbiol 38 2994 2997

18. ColeTJ

1997 Growth monitoring with the British 1990 growth reference. Arch Dis Child 76 47 49

19. VictoraCG

HuttlySR

FuchsSC

OlintoMT

1997 The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol 26 224 227

20. CorbettEL

ChurchyardGJ

CharalambosS

SambB

MoloiV

2002 Morbidity and mortality in South African gold miners: impact of untreated disease due to human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 34 1251 1258

21. GrantAD

SidibeK

DomouaK

BonardD

Sylla-KokoF

1998 Spectrum of disease among HIV-infected adults hospitalised in a respiratory medicine unit in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2 926 934

22. JeenaPM

CoovadiaHM

ThulaSA

BlytheD

BuckelsNJ

1998 Persistent and chronic lung disease in HIV-1 infected and uninfected African children. Aids 12 1185 1193

23. ArpadiSM

2000 Growth failure in children with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 25 S37 S42

24. BuchaczK

RogolAD

LindseyJC

WilsonCM

HughesMD

2003 Delayed onset of pubertal development in children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 33 56 65

25. WeissHA

BuveA

RobinsonNJ

Van DyckE

KahindoM

2001 The epidemiology of HSV-2 infection and its association with HIV infection in four urban African populations. AIDS 15 S97 S108

26. GregsonS

NyamukapaCA

GarnettGP

MasonPR

ZhuwauT

2002 Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet 359 1896 1903

27. LopmanBA

GarnettGP

MasonPR

GregsonS

2005 Individual level injection history: a lack of association with HIV incidence in rural Zimbabwe. PLoS Med 2 e37 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020037

28. GomoE

RusakanikoS

MashangeW

MutswangaJ

ChandiwanaB

2005 Household survey of HIV-prevalence and behaviour in Chimanimani District, Zimbabwe Cape Town, South Africa Human Social Research Council

29. BrookesH

ShisanaO

RichterL

2004 The national household HIV prevalence and risk survey of South African children Cape Town Human Social Research Council

30. NewellML

CoovadiaH

Cortina-BorjaM

RollinsN

GaillardP

2004 Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: a pooled analysis. Lancet 364 1236 1243

31. SohCH

OleskeJM

BradyMT

SpectorSA

BorkowskyW

2003 Long-term effects of protease-inhibitor-based combination therapy on CD4 T-cell recovery in HIV-1-infected children and adolescents. Lancet 362 2045 2051

32. WalkerAS

DoerholtK

SharlandM

GibbDM

2004 Response to highly active antiretroviral therapy varies with age: the UK and Ireland Collaborative HIV. Paediatric Study Aids 18 1915 1924

33. NewellML

PatelD

GoetghebuerT

ThorneC

2006 CD4 cell response to antiretroviral therapy in children with vertically acquired HIV infection: is it associated with age at initiation? J Infect Dis 193 954 962

34. Bakeera-KitakaS

McKellarM

SniderC

KekitiinwaA

PiloyaT

2008 Antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infected adolescents in Uganda: assessing the impact on growth and sexual maturation. Pediatr Infect Dis J 3 97 104

35. KekitiinwaA

LeeKJ

WalkerAS

MagandaA

DoerholtK

2008 Differences in factors associated with initial growth, CD4, and viral load responses to ART in HIV-infected children in Kampala, Uganda, and the United Kingdom/Ireland. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 49 384 392

36. Bikaako-KajuraW

LuyirikaE

PurcellDW

DowningJ

KaharuzaF

2006 Disclosure of HIV status and adherence to daily drug regimens among HIV-infected children in Uganda. AIDS Behav 10 S85 S93

37. FerrandRA

LoweS

WhandeB

MunaiwaL

LanghaugL

2009 Survey of children accessing HIV services in a high HIV prevalence setting: time for HIV-infected adolescents to count? Bull World Health Organ In press

38. Ministry of Health and Child Welfare 2007 Zimbabwe national HIV and AIDS estimates 2007 Harare, Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 2- Berberin: přírodní hypolipidemikum se slibnými výsledky

- Léčba bolesti u seniorů

- Příznivý vliv Armolipidu Plus na hladinu cholesterolu a zánětlivé parametry u pacientů s chronickým subklinickým zánětem

- Červená fermentovaná rýže účinně snižuje hladinu LDL cholesterolu jako vhodná alternativa ke statinové terapii

- Jak postupovat při výběru betablokátoru − doporučení z kardiologické praxe

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Effectiveness of Non-nucleoside Reverse-Transcriptase Inhibitor-Based Antiretroviral Therapy in Women Previously Exposed to a Single Intrapartum Dose of Nevirapine: A Multi-country, Prospective Cohort Study

- The Global Research Neglect of Unassisted Smoking Cessation: Causes and Consequences

- Adolescent HIV—Cause for Concern in Southern Africa

- Impact of Antiretroviral Therapy on Incidence of Pregnancy among HIV-Infected Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Cohort Study

- Automated Detection of Infectious Disease Outbreaks in Hospitals: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Event Rates, Hospital Utilization, and Costs Associated with Major Complications of Diabetes: A Multicountry Comparative Analysis

- Pretreatment CD4 Cell Slope and Progression to AIDS or Death in HIV-Infected Patients Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy—The CASCADE Collaboration: A Collaboration of 23 Cohort Studies

- Can Broader Diffusion of Value-Based Insurance Design Increase Benefits from US Health Care without Increasing Costs? Evidence from a Computer Simulation Model

- Causes of Acute Hospitalization in Adolescence: Burden and Spectrum of HIV-Related Morbidity in a Country with an Early-Onset and Severe HIV Epidemic: A Prospective Survey

- Developing Global Maps of the Dominant Vectors of Human Malaria

- Guidance for Developers of Health Research Reporting Guidelines

- Packages of Care for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- A New Policy on Tobacco Papers

- Ghostwriting at Elite Academic Medical Centers in the United States

- Measuring hsCRP—An Important Part of a Comprehensive Risk Profile or a Clinically Redundant Practice?

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Packages of Care for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- Measuring hsCRP—An Important Part of a Comprehensive Risk Profile or a Clinically Redundant Practice?

- Developing Global Maps of the Dominant Vectors of Human Malaria

- Guidance for Developers of Health Research Reporting Guidelines

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání