-

Články

Reklama

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

ReklamaDifferent Infectivity of HIV-1 Strains Is Linked to Number of Envelope Trimers Required for Entry

Our estimates of the HIV-1 entry stoichiometry, that is the number of envelope glycoprotein trimers needed to mediate fusion of viral and target cell membrane, close an important gap in our understanding of the HIV entry process. As we show, stoichiometric requirements for envelope trimers differ between HIV strains and steer virus entry efficacy and virus entry kinetics. Thus, the entry stoichiometry has important implications for HIV transmission, as demands on trimer numbers will dictate the infectivity of virus populations, target cell preferences and virus inactivation by trimer-targeting inhibitors and neutralizing antibodies. Beyond this, our data contribute to the general understanding of mechanisms and energetic requirements of protein-mediated membrane fusion, as HIV entry proved to follow similar stoichiometries as described for Influenza virus HA and SNARE protein mediated membrane fusion. In summary, our findings provide a relevant contribution towards a refined understanding of HIV-1 entry and pathogenesis with particular importance for ongoing efforts to generate neutralizing antibody based therapeutics and vaccines targeting the HIV-1 envelope trimer.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004595

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004595Summary

Our estimates of the HIV-1 entry stoichiometry, that is the number of envelope glycoprotein trimers needed to mediate fusion of viral and target cell membrane, close an important gap in our understanding of the HIV entry process. As we show, stoichiometric requirements for envelope trimers differ between HIV strains and steer virus entry efficacy and virus entry kinetics. Thus, the entry stoichiometry has important implications for HIV transmission, as demands on trimer numbers will dictate the infectivity of virus populations, target cell preferences and virus inactivation by trimer-targeting inhibitors and neutralizing antibodies. Beyond this, our data contribute to the general understanding of mechanisms and energetic requirements of protein-mediated membrane fusion, as HIV entry proved to follow similar stoichiometries as described for Influenza virus HA and SNARE protein mediated membrane fusion. In summary, our findings provide a relevant contribution towards a refined understanding of HIV-1 entry and pathogenesis with particular importance for ongoing efforts to generate neutralizing antibody based therapeutics and vaccines targeting the HIV-1 envelope trimer.

Introduction

To infect cells, HIV-1 virions need to fuse their membrane with the target cell membrane, a process triggered by the viral envelope (env) glycoprotein trimer [1], [2]. Due to its key function in the virus life cycle and as prime target for neutralizing antibodies and entry inhibitors, analyses of env trimer structure and function remain in the focus of current HIV vaccine and drug research [3]–[5]. Each env trimer consists of three heterodimeric protomers, composed of the non-covalently associated gp120 surface and gp41 transmembrane subunits. Binding of gp120 to the primary receptor CD4 on target cells triggers conformational changes in gp120 that expose the binding site of a co-receptor, most commonly CCR5 or CXCR4 [6]. Subsequent co-receptor binding activates the gp41 transmembrane subunits, which triggers a prototypic class I fusion process via insertion of the N-terminal fusion peptides into the target cell membrane. Refolding of the gp41 N - and C-terminal heptad repeat regions into six-helix bundles drives approximation and fusion of viral and target cell membranes [1], [7], [8].

While the HIV entry process has been defined in considerable detail, we currently lack information on the stoichiometric relations of interacting molecules. Likewise, the thermodynamic requirements of membrane fusion pore formation and pore enlargement, enabling passage of the viral core into the target cell cytoplasm, are only partially understood [9]–[11]. The energy required for the entry process is generated by structural rearrangements of the envelope trimer that follow receptor binding [7], [8], [12]. How many trimers must engage in receptor interactions (a number referred to as stoichiometry of entry) [13]–[15] in order to elicit the required energy to complete fusion has not been conclusively resolved. Whether HIV needs one or more trimers to complete entry will strongly influence virion infectivity and efficacy of neutralizing antibodies targeting the trimer. Previous studies resulted in contradicting stoichiometry estimates, suggesting that either a single trimer is sufficient for entry [13] or that between 5 to 8 trimers are required [14], [15]. In comparison, for Influenza A virus, which achieves membrane fusion through the class I fusion protein hemagglutinin (HA), postulated necessary HA trimer numbers range from 3 to 4 [16]–[18] to 8 to 9 [13]. Calculations based on the energy required for membrane fusion suggested that indeed the refolding of a single HIV envelope trimer could be sufficient to drive entry [7], [8]. Numerous lines of evidence however suggest that several env-receptor pairings are commonly involved in the HIV entry process. Electron microscopy analysis of HIV entry revealed the formation of an “entry claw” consisting of several putative env-receptor pairs [19], which is supported by biochemical analyses indicating that the number of CCR5 co-receptors needed for virus entry differs among HIV-1 isolates and requires up to 6 co-receptors [20], [21].

Precise delineation of the stoichiometry of entry, as we present it here, substantially contributes to our understanding of HIV pathogenesis by defining a viral parameter that steers virus entry capacity, potentially shapes inter - and intra-host transmission by setting requirements for host cell receptor densities, and by defining stoichiometric requirements for virion neutralization. The latter is of particular importance considering the ongoing efforts to generate neutralizing antibody based therapeutics and vaccines targeting the HIV-1 entry process [3], [4], [22].

Results

The number of envelope trimers required for entry differs among HIV-1 isolates

To estimate the stoichiometry of entry (in the following referred to as T) we employed a previously described combination of experimental and modelling analyses [13]–[15]. Our strategy centers on the analysis of env pseudotyped virus stocks carrying mixed envelope trimers consisting of functional (wt) and dominant-negative mutant env, where a single dominant-negative env subunit incorporated into a trimer renders the trimer non-functional. We included envs of 11 HIV-1 strains in our analysis covering subtypes A, B and C and a range of env characteristics such as primary and lab-adapted strains, different co-receptor usage and different neutralization sensitivities (Table 1).

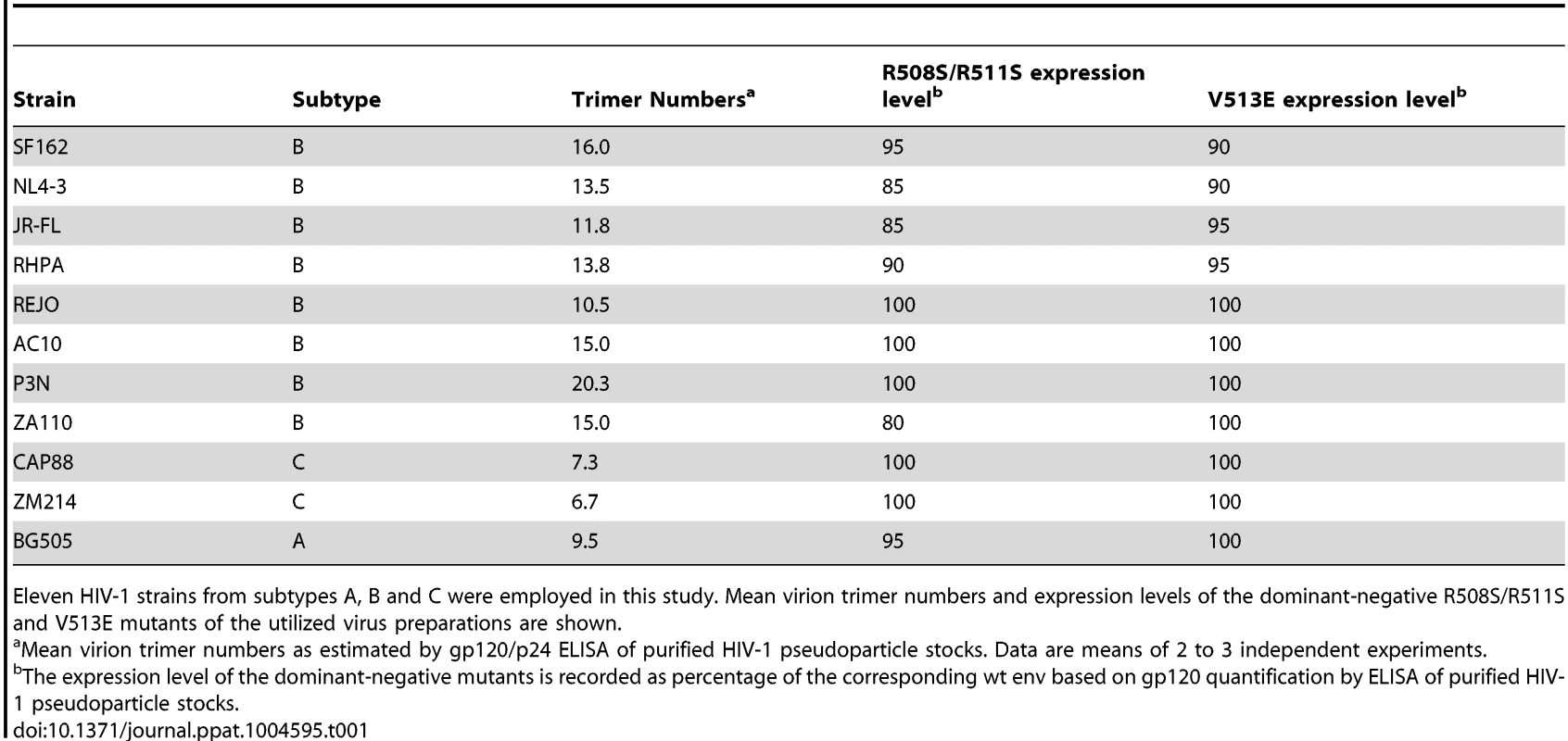

Tab. 1. HIV-1 strains and mutants.

Eleven HIV-1 strains from subtypes A, B and C were employed in this study. Mean virion trimer numbers and expression levels of the dominant-negative R508S/R511S and V513E mutants of the utilized virus preparations are shown. To derive estimates of T from mixed trimer experiments two key parameters need to be considered: the mean virion trimer numbers and the distribution of virion trimer numbers across a virion population [14], [15]. To assess virion trimer numbers, we determined p24 and gp120 content of purified virus stocks by ELISA. Although only an approximation, as also partially shed and non-functional trimers are accounted for, this analysis yielded upper limits of virion trimer content. We observed between 6 to 20 trimers per virion among the 11 strains probed (Table 1), which is in close agreement with previous estimates of HIV-1 virion trimer content [23]–[28]. While trimer incorporation into pseudotyped particles may be lower than on replication-competent virus [29], this does not preclude estimation of T as trimer content is controlled for in our mathematical analysis. Since available experimental data do not provide information on the distribution of trimers across virion populations (i.e. frequencies of virions with a given trimer number in the population), we utilized previously determined trimer number variation across virions in our modeling [26].

Key in our experimental design are dominant-negative env mutants. To obtain robust estimates of T we performed the experiments with two individual env mutations that both lead to a complete loss in entry capacity, either by a mutation of the Furin cleavage site (R508S/R511S) [13], [30], [31] or a mutation of the gp41 fusion peptide (V513E) [13], [32]. Importantly, expression levels of the mutant envs were in the range of 80 to 100% of the corresponding wt envs (Table 1), ascertaining that during mixed trimer experiments env expression levels on virions follows the ratio of wt and mutant env plasmids transfected into virus producer cells.

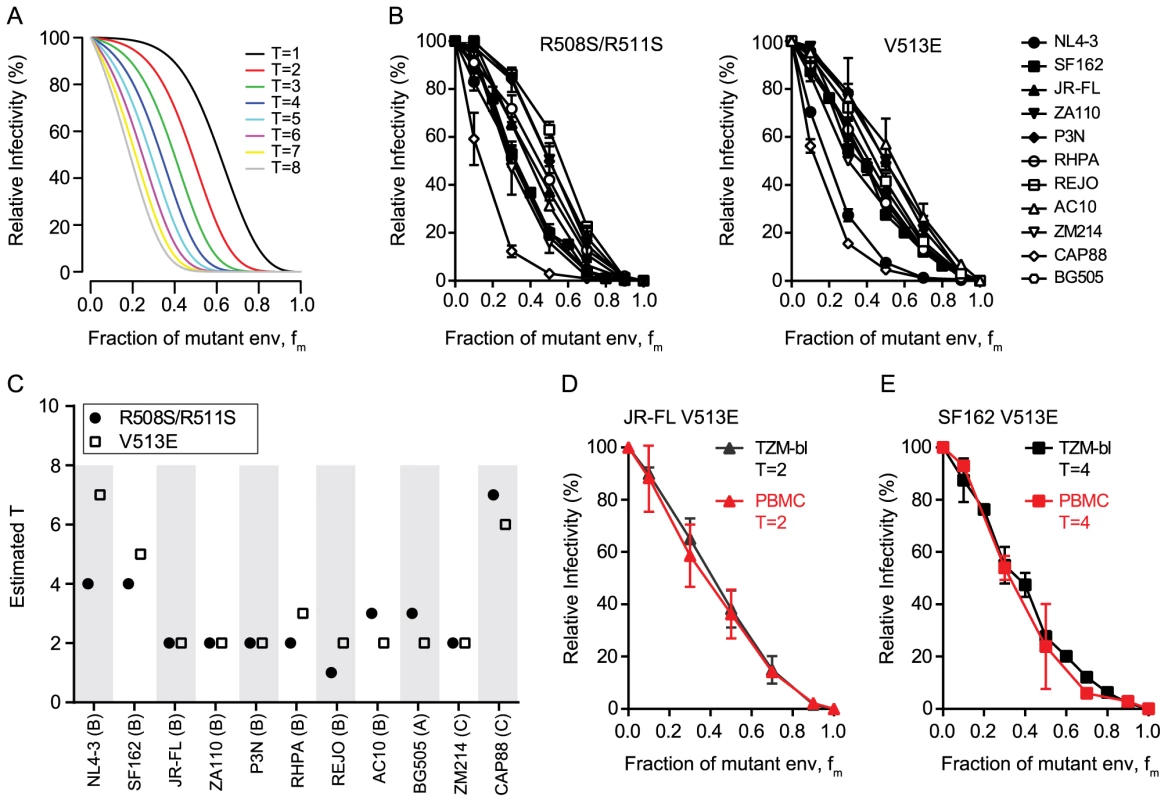

To assess T, mixed trimer expressing pseudovirus stocks of each strain were generated by transfecting producer cells with different ratios of mutant and wt env plasmids ranging from 0 to 100% of the dominant-negative mutant env. The resulting virus stocks were probed for infectivity on TZM-bl reporter cells and infectivity was plotted as function of mutant env content (Fig. 1A and B). Based on our model [15], differences in T result in different infectivity plots in this graphical analysis (Fig. 1A). Intriguingly, the 11 envs showed variable patterns suggesting that the strains differ in T (Fig. 1B). The mixed trimer infectivity data (Fig. 1B) and the mean virion trimer numbers (Table 1) were then used to infer T of each strain by our model. This resulted in estimates of T ranging from 1 to 7 trimers for the 11 HIV strains tested (Fig. 1C, S1 Table and S1 Fig.), with the majority of strains requiring 2 to 3 trimers for entry. Of note, the data derived with the V513E and R508S/R511S mutant returned closely matching results with identical estimates for T (n = 4) or estimates differing only by 1 (n = 6) (Fig. 1C). The only higher discrepancy was observed for the highly neutralization sensitive, T cell line adapted strain NL4-3 where the two env mutations appeared to have individual effects on the readout but both yielded estimates of T that were amongst the highest in the env panel (T = 7 with V513E and T = 4 with R508S/R511S).

Fig. 1. HIV-1 strains differ in the number of trimers required for entry.

(A) Theoretical predictions of relative virus infectivity over the fraction of dominant-negative mutant env (fm) according to our model. Curves for T ranging from 1 to 8 are shown assuming the trimer number distribution across virions to follow a discretized Beta distribution with constant mean 12.95 and variance 45 [15]. (B) Relative infectivity of mixed trimer infection experiments with 11 HIV-1 strains using the R508S/R511S (left) and V513E (right) dominant-negative env mutants. Infectivity of pseudotyped virus stocks expressing the indicated ratios of wild type and dominant-negative mutant envs was measured on TZM-bl reporter cells. Infectivity of virus stocks containing solely wt envelope were set as 100%. Data depict mean and SD from 2 to 4 independent experiments. For each virus the individual curve fits resulting from the model to the obtained data were evaluated (S1 Fig.). (C) Mathematical estimates of T derived from the data shown in (B). The R508S/R511S (black circles) and V513E (open squares) mutations were analyzed individually. Bootstrap analyses demonstrating the robustness of the obtained estimates of T are shown in S1 Fig. (D and E) Mixed trimer virus stocks for strain JR-FL (D) and SF-162 (E) carrying the V513E mutation were assayed on healthy donor PBMC and compared to data obtained with TZM-bl target cells. Data depict mean and SD from 2 independent experiments. To verify that the mathematical approach (in the following referred to as “basic model”) provides a valid estimate of T, we probed several alternative analyses of the data shown in Fig. 1B. These analyses incorporate previously described extensions of the basic model that account for additional parameters that could potentially influence data acquisition and analysis [15]. The model extensions showed for the majority of strains a significantly improved curve fit to the experimental data (S1 Table). However, these analyses frequently yielded highly divergent values of T and the additional model parameters included in the model extensions for the two dominant-negative mutants of the same strain (S1 Table and exemplified for the CAP88 Env in S2 Fig.). This was in stark contrast to the basic model where the two independent T estimates of each strain were with few exceptions in close agreement (Fig. 1C and S1 Fig.). As we can safely assume that the parameter estimates for the two different mutations of the same strain should be similar we can reject the model extensions. A further indication that the model extensions we probed are not valid in the context of our analysis was that the derived estimates of T were in many cases implausibly high whereas the basic model generated estimates that fit the described range of trimer levels on HIV virions. We are thus confident that the basic model we utilize for the estimation of T is valid and provides robust estimates.

The mean virion trimer number of the probed virus stocks is an important model parameter in our analysis of T and fluctuations in the mean virion trimer number may therefore influence the estimates. To test the influence of mean virion trimer number variation on our estimates of T we performed additional data analyses where instead of the measured individual trimer numbers (Table 1), identical mean trimer numbers for all 11 strains were assumed. We chose 3 values for this comparison that covered the range of trimer numbers measured across our panel: mean trimer numbers of 5 and 26 (representing the lowest and highest trimer contents measured in individual experiments) and a mean trimer number of 13, the mean of trimer numbers measured across our virus panel. Applying these trimer numbers to our data set we obtained estimates of T ranging from 1 to 17 trimers (S3A Fig.).

To determine the mean virion trimer numbers of the virus stocks we measured gp120 and p24 contents. This allows to derive virion numbers based on previously reported estimates of 1200 to 2500 p24 molecules per virion [23], [24], [33]. We chose an average estimate of 2000 p24 molecules per virion to derive the mean trimer numbers shown in Table 1. To investigate the influence of p24 assumptions on our analysis we also tested a higher p24 content estimate of 2400 molecules per virion as recently reported [33], consequently yielding 20% higher mean virion trimer numbers across all viruses. Employing these 20% higher trimer numbers in our analysis had only a modest effect on the T estimates yielding identical or slightly higher (mostly by one trimer) estimates of T (S3B Fig.). While these analyses confirm that absolute values of T vary depending on the mean virion trimer number assumed for the analysis, the differences in T among the 11 strains persisted, highlighting that they reflect qualitative entry properties of the respective envs. Hence, independent of the absolute mean trimer numbers, differences in T between viral strains can be detected by our approach.

As a further assay verification we tested the influence of target cells on our estimation of T. We reasoned that if our experimental approach truly measures the stoichiometry of entry, then the obtained data should be a sole function of the envelope trimer and not be influenced by target cell type and receptor density. We thus chose TZM-bl cells as target cells for their known reproducible performance and good signal to noise ratio in the luciferase reporter readout. Since these engineered cells overexpress the entry receptors of HIV and thus do not reflect features of physiological relevant target cells, we sought to verify that the obtained T estimates are indeed independent of the target cells used. To this end we chose two envelopes which yielded a low T estimate (primary isolate JR-FL, T = 2) and a high T estimate (lab-adapted strain SF162, T = 4 to 5) on TZM-bl cells and repeated the estimation of T on PBMC as target cells (Fig. 1D and E and S4 Fig.). As anticipated, we obtained for both viruses almost identical curves and T estimates as with the TZM-bl reporter cells, confirming that estimates of T are truly independent of the target cell type. Hence, use of TZM-bl cells for our assay setup is appropriate and the estimated T values are valid for physiologically relevant target cells of HIV-1.

Increased virus entry fitness is reflected by low entry stoichiometry

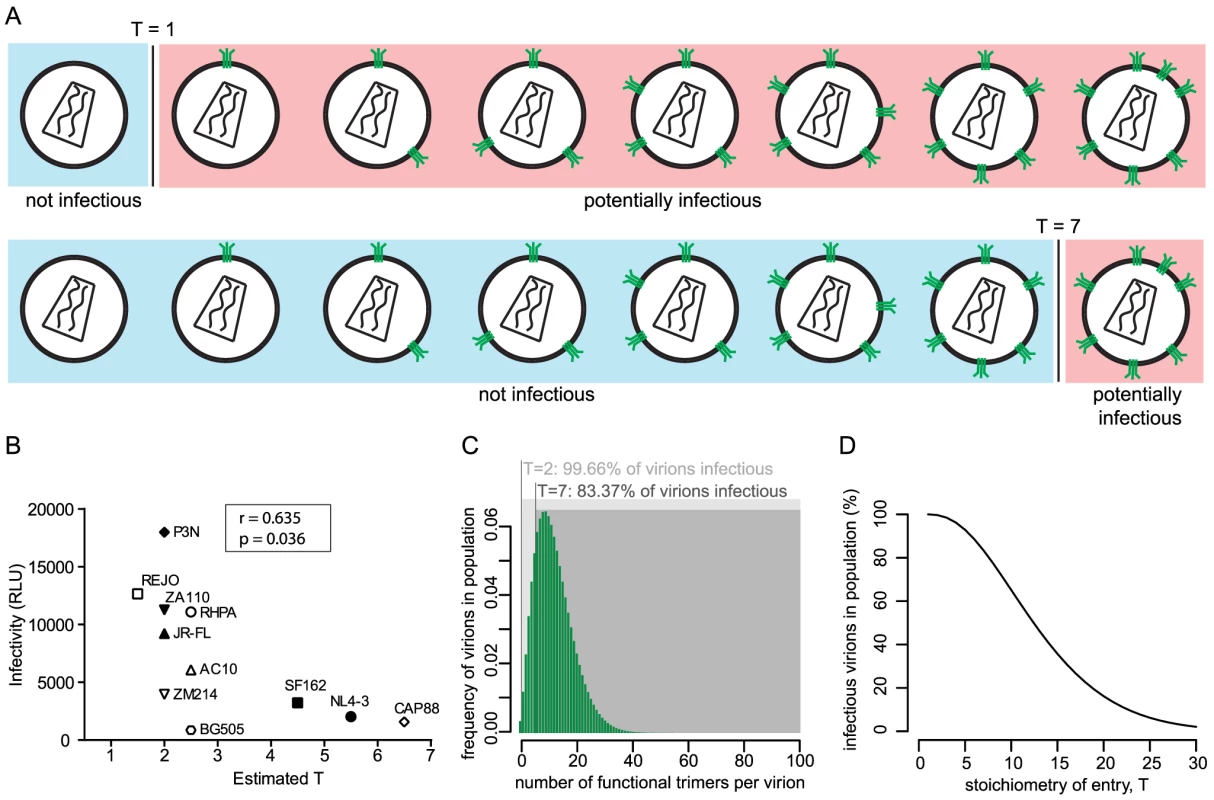

The entry stoichiometry of a strain can be expected to influence virus population infectivity as strains with a low T will benefit from a higher proportion of the virus population carrying the required minimum trimer number (Fig. 2A). To directly probe the influence of T on virus infectivity we assessed the in vitro infectivity of the 11 HIV-1 strains in our panel. Of note, in the context of pseudoviruses infectivity is solely determined by the Env genes. Intriguingly, infectivity proved to be inversely correlated with T (r = −0.635, p = 0.036; Fig. 2B) indicating that strains that accomplish entry with low T are more infectious than strains with high T. Of note, we observed very divergent infectivities also for strains with very similar estimates of T (Fig. 2B). This is likely caused by different mean trimer numbers of the strains, as the mean trimer number in conjunction with T dictates virion population infectivity (Fig. 2A, C and D). For instance, amongst the viruses with T = 2 strain P3N has the highest infectivity and highest mean virion trimer number (20.3) whereas ZM214, the strain with lowest infectivity also has the lowest mean virion trimer number (6.7) measured across these viruses (Table 1). It can expected that additional factors beyond T and trimer numbers, such as propensity to shed gp120 or differential affinity for CD4, which are not covered by our analysis, may further contribute to different infectivity of the strains.

Fig. 2. The entry stoichiometry governs virus population infectivity.

(A) Scheme depicting the influence of the entry stoichiometry on virus population infectivity. Different Ts (exemplified here: T = 1 and T = 7) will determine the minimum number of trimers that a virion requires in order to be infectious. (B) Correlation analysis (Pearson) of virus strain infectivity (measured by infection of TZM-bl reporter cells and expressed in arbitrary relative light units (RLU) per µl of virus stock) and the estimated T (plotted as mean of the independent R508S/R511S and V513E estimates shown in Fig. 1C). Virus infectivities are depicted as mean values derived from 3 independent experiments. (C) Mathematical modeling to investigate the influence of entry stoichiometry on virion population infectivity. The data depict how T = 2 and T = 7 translate into different fractions of a virion population being potentially infectious, in dependence on the trimer number distribution across the virion population. As shown in (D), the overall infectivity of a virus population decreases with increasing T. For (C) and (D) we assumed the trimer number distribution across virions to follow a discretized Beta distribution with constant mean 12.95 and variance 45 [15]. To investigate the interplay between entry stoichiometry and infectiousness of a virus population in more detail, we performed mathematical analyses of the relation between entry stoichiometry and trimer numbers per virion of a virus population. We found that indeed the entry stoichiometry steers virus population infectivity, with a higher entry stoichiometry resulting in a lower fraction of potentially infectious virions (Fig. 2C and D). Hence, the T of a strain and the therewith linked entry capacity may potentially contribute to the infectious to non-infectious particle ratio which is known to be low for HIV-1 [24].

Perturbation of trimer integrity induces changes in entry stoichiometry

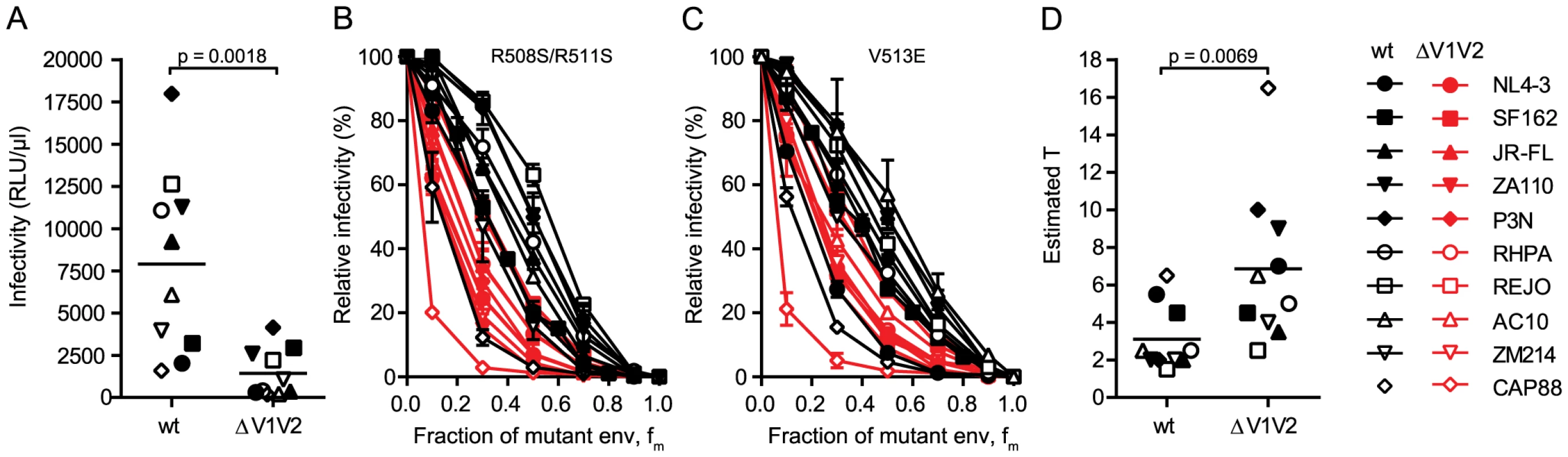

To further explore the relation between virus infectivity and T we analyzed envs with deletions of the gp120 variable loops 1 and 2 (V1V2) and compared them to the matching wildtype envs. As we and others have previously shown, V1V2 deletion causes a dramatic reduction of virus infectivity through impairment of trimer integrity (Fig. 3A and [34]–[38]). When we probed T and compared the infectivity curves of the wt and V1V2-deleted env pairs, we observed distinct curve shifts of the V1V2-deleted envs across the majority of strains (Fig. 3B and C). Indeed, T of the V1V2-deleted envs proved significantly increased compared to the matching wt envs (Fig. 3D; mean T of 3.1 for wt envs versus mean T of 6.85 for V1V2-deleted envs; paired t test p = 0.0069). Importantly, this reduction in entry efficiency and the ensuing high estimates for T upon V1V2 deletion are not simply caused by reductions in env content of these virions, as V1V2-deleted env is expressed to similar levels on virions as the corresponding wt env (80–100% of wt, S5 Fig.). While expression levels of trimers certainly influence the estimates of T, we verified that the observed env content reduction of V1V2 deleted viruses was too low to inflict an overestimation of T (S5 Fig.) highlighting that indeed functional properties and not quantity of the respective wt and ΔV1V2 envelopes are decisive in defining T.

Fig. 3. V1V2 deletion impairs virus infectivity and is reflected by a high stoichiometry of entry.

(A) Comparison of infectivity of pseudoviruses expressing wt and V1V2-deleted envs upon infection of TZM-bl cells. Data points depict mean values of luciferase reporter activity per µl virus stock measured in 3 independent experiments. The p-value was calculated by a paired t-test. (B and C) Relative infectivity of mixed trimer infection experiments of 10 wt envs and their V1V2 deleted variants using the R508S/R511S (B) and the V513E (C) dominant-negative mutations are shown. Infectivity of pseudotyped virus stocks expressing the indicated ratios of dominant-negative mutant envs was measured on TZM-bl cells. Infectivity of virus stocks containing solely functional envelope were set as 100%. Data depict mean and SD from 2 to 4 independent experiments. (D) Estimates of T for the wt and V1V2-deleted envs derived from mixed trimer experiments. Data points are the mean of the individual estimates of T obtained with the R508S/R511S and V513E dominant-negative mutations. The p-value was calculated by a paired t-test. To further investigate the interplay between trimer numbers and T we produced pseudoviruses which expressed JR-FL wt and JR-FL ΔV1V2 with a deletion of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail (CT) as this is known to lead to an increased incorporation of trimers into virions [39], [40]. Indeed, CT deletion resulted in approximately 2-fold increased levels of trimers on virions (S6A–S6B Fig.). In support of the strong interplay between virion trimer numbers and infectivity thresholds defined by T, the infectivity of both viruses upon CT deletion was increased (S6C Fig.). Intriguingly, the increase in infectivity upon CT deletion was higher for JR-FL ΔV1V2 (9-fold) compared to JR-FL wt (2-fold), highlighting that envelopes with a reduced entry capacity, as here JR-FL ΔV1V2, benefit more if virions carry higher trimer numbers and thus meet the stoichiometric requirements for entry (S6D–S6E Fig.).

Virus entry kinetics reflect requirements for trimer numbers during entry

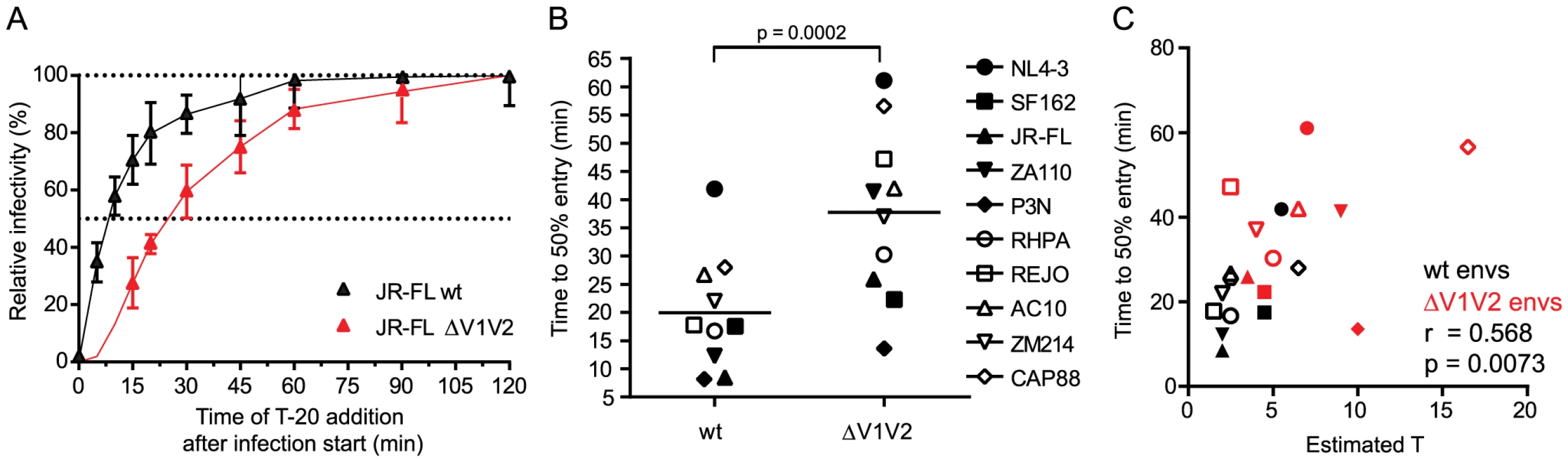

The number of trimers required for HIV entry likely influences virus infectivity in many ways. Besides determining a threshold trimer content that renders virions infectious, different T's could also manifest in different kinetics of the entry process as viruses with higher T may require more time to recruit and engage the necessary number of trimer-receptor pairings. To determine virus entry kinetics we employed a time-of-inhibitor addition experiment to derive the time required per virus strain to reach 50% of entry into target cells (Fig. 4A and S7A–S7B Fig.). Synchronized infection following spinoculation and temperature arrest in this assay setup allows assessment of entry kinetics solely as factor of envelope function post attachment to the target cells. When comparing the entry kinetics of the wt and V1V2-deleted strains we found that V1V2-deleted envs showed significantly delayed entry into target cells (Fig. 4B; mean times to 50% entry 19.9 minutes for wt envs and 37.7 minutes for V1V2-deleted envs; paired t-test p = 0.0002). As stated above, a potential explanation for this is that more time is required for V1V2-deleted strains to assemble a sufficient number of trimers in the virus-target cell contact zone to achieve entry. Indeed, we found a strong correlation between the estimated T and half-maximal entry time when all viruses, wt and V1V2-deleted strains, were analyzed (Fig. 4C; r = 0.568, p = 0.0073) but also for wt envs alone (r = 0.649, p = 0.0307), highlighting that entry stoichiometry and entry kinetics are tightly linked. The fact that we observe a significant correlation between estimated T and half-maximal entry time does however not exclude that additional processes beyond the recruitment of the necessary number of trimer-receptor pairings also influence the entry kinetics. Rates of CD4 and co-receptor binding and speed of the ensuing conformational rearrangements may differ between strains [41] and thereby contribute to the overall variance in entry kinetics. Additionally, for virions with a high T it must be considered that formation of the required number of contacts with the target cell may need longer time periods during which virions may detach again or decay before entry is completed [42].

Fig. 4. Virus entry kinetics correlate with the stoichiometry of entry.

(A) Entry kinetic curves for JR-FL wt and JR-FL ΔV1V2. Synchronized pseudovirus infection of TZM-bl cells following spinoculation was terminated by addition of T-20 at the indicated timepoints. Infectivity reached after 120 minutes was set as 100% and all data were normalized relative to this value. Data are mean and SD from 3 independent experiments. (B) Half maximal entry time for wt and V1V2-deleted envs was calculated from kinetic profiles shown in Fig. 4A and S7B Fig. Time (in minutes) required to reach 50% entry into target cells is depicted. Data shown are means derived from 2 to 4 independent experiments. The p-value was calculated by a paired t-test. (C) Correlation analysis (Pearson) of wt (black symbols) and V1V2-deleted env (red symbols) half-maximal entry time and estimated T. Naturally occurring loss of the N160 glycosylation site influences the stoichiometry of entry

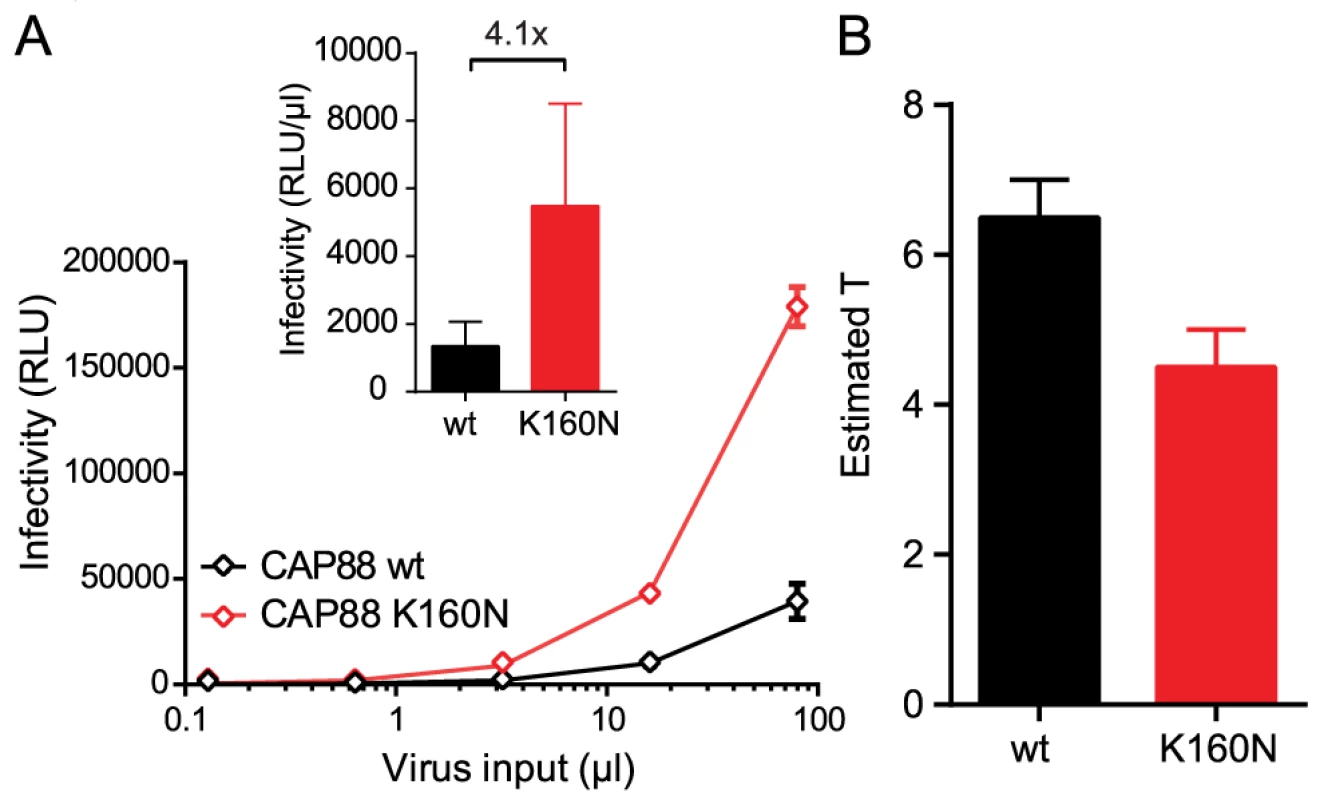

To further explore the relationship between the entry stoichiometry and infectivity we performed additional studies with the subtype C strain CAP88 [43], which had the highest T and lowest infectivity within our panel (Fig. 1B, 1C and 2B). CAP88 is a transmitted/founder virus which carries a lysine (K) at position 160 of gp120, a site frequently targeted by neutralizing antibodies [44]. Among 4894 Env sequences deposited in the Los Alamos HIV Sequence Database asparagine (N) at position 160, as part of an N-linked glycosylation sequon, is with 93.3% the most prevalent residue at position 160 [45]. Loss of this glycosylation site is both associated with escape from PG9/PG16-like antibodies and decreased entry capacity [38], [46]–[48]. Supporting this we found that reconstitution of the N-linked glycosylation site (K160N) in CAP88 results in a 4-fold increase in virus infectivity (Fig. 5A and [38]) highlighting the importance of N160 for env functionality. To probe if the increased infectivity of the CAP88 K160N mutant may be due to changes in trimer structure and function that result in a reduction of T, we analyzed T of CAP88 wt and CAP88 K160N (S8A–S8B Fig.). Indeed, we found that the increased infectivity of CAP88 K160N is reflected by a decreased T (Fig. 5B and S8C Fig.). As this example highlights, changes in trimer structure inferred by naturally occurring mutations, possibly due to antibody escape, can result in a decreased entry capacity of the respective env, which in turn is reflected by an increase in the stoichiometry of entry.

Fig. 5. Loss of the N160 glycosylation site in gp120 steers the stoichiometry of entry and virus infectivity.

(A) Titration of CAP88 wt (black) and CAP88 K160N (red) pseudoviruses on TZM-bl reporter cells. Data shown are mean and SD of luciferase reporter activity upon infection measured in 2 independent experiments. Inset: Infectivity comparison of CAP88 wt and K160N depicted as relative light units (RLU) of luciferase reporter activity per µl of pseudovirus stock upon infection of TZM-bl cells. The fold infectivity difference is indicated. (B) Estimates of T for the CAP88 wt and K160N variant. Mean and range of the individual estimates using the R508S/R511S and V513E dominant-negative mutations are shown. Entry inhibitor escape mutations can increase the stoichiometry of entry

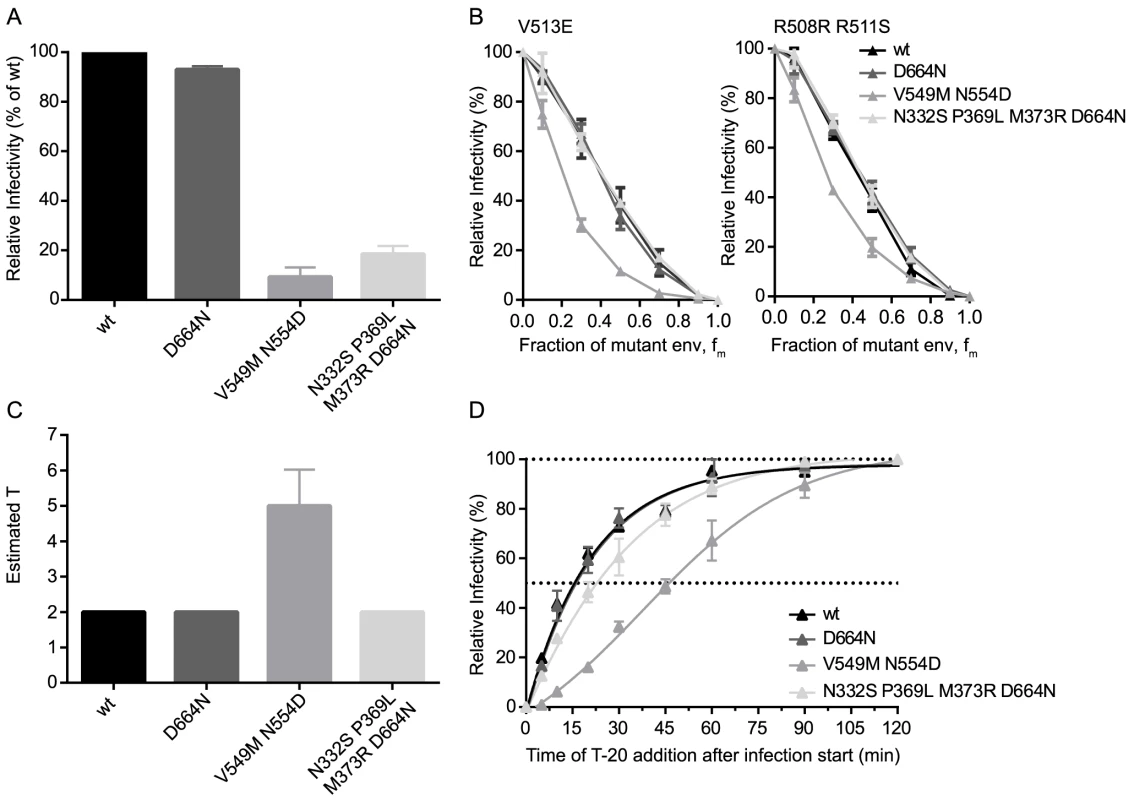

The finding that a single point mutation in the CAP88 env could dramatically alter entry fitness and entry stoichiometry prompted us to further explore the influence of point mutations on env entry phenotype. To this end we selected three JR-FL variants mimicking resistance mutants as they may occur in vivo during neutralization escape: the JR-FL D664N escape mutant resistant to the MPER antibody 2F5, the JR-FL V549M N554D mutant which has a highly increased resistance against the entry inhibitor T-20 [49], and a JR-FL env with point mutations N332S P369L M373R and D664N rendering it resistant against the broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) PGT128, 2G12, b12 and 2F5 (S9 Fig.). While all three JR-FL variants showed similar mean virion trimer numbers as JR-FL wt, we observed differences in env infectivity with the 2F5 escape mutant infecting equally well as JR-FL wt whereas the T-20 and the multiple bnAb escape mutant env showed strongly reduced infectivity at 9% and 19% of JR-FL wt, respectively (Fig. 6A). When we compared the three escape mutant envs and JR-FL wt in the mixed trimer assays we observed a distinct curve shift for both dominant negative mutants of the T-20 escape variant (Fig. 6B), while the other three envs gave almost identical curves. Mathematical analysis of the data indeed revealed that the T-20 escape mutant requires 4 to 6 trimers for entry while all other mutants, like JR-FL wt, require 2 trimers (Fig. 6C). Hence, the T-20 escape mutant showed both, an increase in T and a loss in infectivity while the bnAb escape mutant env maintained T despite showing infectivity loss, confirming our earlier findings that viruses with the same T can still show a wide variation of infectivities (Fig. 2B). This can possibly be attributed to increased trimer decay rates or variations in CD4 and co-receptor engagement, especially since the bnAb escape mutant carried mutations in the CD4 binding site. Interestingly, the increased demand of the T-20 escape mutant for trimers during entry was also reflected in delayed entry kinetics of this env variant (Fig. 6D) [50]. These entry characteristics of the T-20 escape mutant are intriguing as the resistance mutations lie in the heptad repeat region of gp41 and interfere with six-helix bundle formation, which is a key step providing energy for membrane fusion during the entry process [51]. Thus, it is mechanistically plausible that the mutant env may require more trimers for entry to compensate for the disturbed six-helix bundle formation and generate sufficient energy to achieve membrane fusion.

Fig. 6. Point mutations in JR-FL dictate virus infection efficacy and entry stoichiometry.

(A) Infectivities of JR-FL wt and indicated point mutant envs were determined by titration of virus stocks on TZM-bl reporter cells and are shown normalized to JR-FL wt. Data depict mean and SD from 4 independent experiments. (B) Relative infectivity of mixed trimer infection experiments with the specified JR-FL variants using the R508S/R511S and V513E dominant-negative mutations are shown. Infectivity of pseudotyped virus stocks expressing the indicated ratios of dominant-negative mutant envs was measured on TZM-bl cells. Infectivity of virus stocks containing solely functional envelope were set as 100%. Data depict mean and SD from 2 independent experiments. (C) Mathematical analyses of the data shown in (B) yielded estimates of T, shown here as mean and range of the individual T estimates obtained with the R508S/R511S and V513E dominant-negative mutations. (D) Analysis of virus entry kinetics for the four JR-FL variants were performed as shown S7A Fig. Discussion

Fusion of biological membranes, as required for entry of enveloped viruses, occurs in a plethora of cellular processes. In the case of HIV, fusion is executed by envelope glycoprotein trimers upon interaction with adequate receptor molecules on the target cell membrane [1], [8]. While the principle steps are known and thought to be shared across different biological systems and membrane types [7], [52], [53], the exact mechanisms and stoichiometric and thermodynamic requirements of most membrane fusion processes are not completely resolved [1], [8], [10], [11], [54], [55]. Definition of the components involved in HIV entry and the membrane fusion process is of particular interest as improved understanding of the determinants of HIV entry bears the promise to funnel the development of enhanced strategies to prevent and treat viral infections [1], [7]. The efficacy of HIV entry shapes inter - and intra-host transmission and determines the vulnerability to a range of therapeutic and preventive strategies such as neutralizing antibodies, entry inhibitors and antibody based vaccines. Considering that the stoichiometry of entry defines the number of trimers required for a virus to infect, in turn it also defines the number of trimers on a virion that need to be blocked by neutralizing antibodies. Depending on the stoichiometry of entry the quantities of antibody needed for effective neutralization can therefore vary substantially [56] (S10 Fig.).

To resolve molecular requirements of HIV membrane fusion, we explored in the present study the stoichiometry of HIV-1 entry (T), which defines the number of envelope trimers required per virion to fuse with the target cell membrane and thereby initiate infection [13]–[15]. Our estimates of T are based on a combined strategy of experimental data acquisition and mathematical modelling. We analyzed envelopes from 11 HIV-1 strains including different HIV subtypes, CCR5 and CXCR4 users, and envelopes with open (lab adapted strains) and closed (primary isolates) trimer conformation. We found that T differs substantially between individual strains with measurements ranging from 1 to 7 trimers that are required for entry. While a previous study suggested that HIV −1 isolates generally require only a single trimer for entry [13] our analysis retrieved values for T which were, with one exception (strain REJO), greater than 1, supporting the findings of alternate modelling approaches by us and others [14], [15]. Of note, only one of the two dominant-negative env mutants we probed recorded T = 1 for the strain REJO while the other mutant yielded an estimate of T = 2. Thus, while our data cannot exclude that T = 1 for some strains, based on our observations a range of different entry stoichiometries as we describe here seems more plausible.

We postulate two potential underlying causes for the variations in T we observe across strains. Our estimates are based on virion trimer content measurements by ELISA and are therefore a composite of functional and non-functional trimers present on virions. Considering this, a high estimate of T may be derived as the consequence of premature trimer inactivation through rapid trimer decay [38], [57], or a spontaneous adoption of the CD4-bound conformation [57], [58]. In both cases high estimates of T would reflect a decreased proportion of functional trimers on virions. Alternatively, a high T may be required by envelopes which have adopted a trimer conformation with a low energetic state as described for the open conformation of lab adapted strains [58],[59]. There, the lack in energy released upon trimer conformational rearrangements may be compensated by higher trimer numbers roped into the entry process. Most notably, for all three wildtype strains that yielded high estimates of T as well as the V1V2-deleted env variants, the high T was associated with a low infectivity (Fig. 2B, 3A and 3D). The latter is particularly intriguing as it supports the possibility that env deficiencies in entry can be partially overcome by higher numbers of trimers engaged during the entry process. Interesting insights also stem from the SF162/P3N env pair: P3N was isolated from a rhesus macaque after successive rapid transfer following initial challenge with SHIV-SF162 [60]. While SF162 has a high estimate of T of 4 to 5, P3N has a T of 2 and is the most infectious env in our panel (Fig. 2B). Thus, HIV (or SIV) has the potential to evolve from a less fit to a highly transmissible env in vivo. The exact mutations responsible for the different phenotypes remain to be determined; as we previously showed, the V1V2 domains of SF162 and P3N appear to play an important role in this regard [38].

A high T was also linked with slower virus entry kinetics (Fig. 4C) suggesting that engagement of multiple trimer-receptor pairings requires prolonged time periods. A similar relationship between kinetics of membrane fusion and the number of involved fusion proteins has been previously demonstrated for SNARE (Soluble NSF Attachment protein Receptor) complex mediated membrane fusion [61], [62] and Influenza virus membrane fusion [16], [17]. The interplay between HIV-1 entry stoichiometry and entry kinetics our study reveals thus underscores the general finding that the kinetics of membrane fusion processes are governed, at least in part, by the number of participating fusion proteins.

We rate the tight association of T with functional properties of the envelopes, namely entry capacity and entry kinetics, as a strong indicator of the validity of our analysis. Nevertheless, such estimates of T can only be an approximation as certain parameters which influence the estimates cannot be determined experimentally and assumptions need to be made for the mathematical analysis. In the literature different approaches towards modelling of mixed trimer experiments have been described and led to partially deviating results, highlighting the importance of validating the models and parameters used [13], [14], [63]. Virion trimer numbers are commonly estimated from gp120 and p24 ELISA data (Table 1) [23], [24]. These analyses yield values for the average envelope content of virions but do not provide information on the frequency distribution of viruses carrying different trimer numbers across a virion population. The latter is a factor that impacts on the interpretation of mixed trimer experiments [14], [15], [64]. Additionally, env content estimates by ELISA do not deliver information on env functionality, hence functional and non-functional trimers will be accounted for [65]. A further potential limitation stems from the nature of the mixed trimer experiments which require that all combinations of envelopes probed lead to a random trimer formation. Since preferential formation of homotrimers could strongly influence results obtained from mixed trimer experiments, we controlled for equal expression levels of the co-expressed env variants. In addition, previous studies from us and others indicate that related env variants indeed form randomly mixed trimers [13], [66], [67]. As outlined in our previous work, we have incorporated in our mathematical model several functions to capture these parameters involved in HIV entry and carefully verified the validity of our approach in the current study both in vitro and in silico (S1–S2 Fig., S1 Table and [15], [63], [68]). Nevertheless, this does not exclude that additional parameters beyond T contribute to the variation in entry phenotype between individual HIV-1 strains. For instance, differences in trimer stability or affinities for CD4 and co-receptors could significantly impact on virus entry efficacy without direct influence on T.

Membrane fusion via the stalk-pore mechanism [11] is a multi-step process that ultimately depends on energy provided by fusion proteins [9], [11], [52], [69]. Approximation of two membranes is followed by fusion of the two proximal membrane leaflets, forming the hemifusion stalk intermediate. Subsequent fusion of the distal membrane leaflets creates a fusion pore, which may either expand or close again depending on the forces exerted on the membranes. Viral envelope glycoproteins, such as the HIV-1 env or Influenza virus HA trimer, are metastable structures that undergo a series of conformational changes following receptor engagement which releases energy utilized in the fusion process [7], [8]. Although the energy required for hemifusion stalk formation could potentially be recovered from refolding of a single envelope glycoprotein trimer [8], [55], subsequent formation of the fusion pore and pore enlargement are thought to require higher energy levels [9], [11], [70]. Growing evidence suggest that only concerted action of several trimers leads to membrane fusion and maintenance of a fusion pore large enough to allow passage of the HIV capsid [1], [9], [10], [20]. Our estimates that, for the majority of HIV-1 primary isolates, 2 to 3 env trimers are required to mediate infection are thus in accordance with these studies on the mechanisms of membrane fusion. Interestingly, our estimates of the HIV entry stoichiometry resemble those made for Influenza A virus [16]–[18], postulated to require 3 to 4 HA trimers for entry, and vesicular membrane fusion via SNARE complexes, which generate energy during refolding at levels comparable to viral fusion proteins [71]–[73]. In high similarity to HIV and Influenza, also 1 to 3 SNARE complexes appear to be required to induce membrane fusion [61], [62], [74]. To further explore this relationship, we compared reported values of energy required for membrane fusion and energies released by fusion proteins (S11 Fig.). Membrane fusion requires an energy input of 40 to 120 kbT [9], [55], [75], [76]. Refolding of HA trimers into the six-helix bundle conformation was estimated to release 30 to 60 kbT [8], [9], [77] while SNARE complex assembly into 4-helix bundles releases an estimated 19 to 65 kbT [71]–[73], [78]. Considering that 3 to 4 HAs and 1 to 3 SNARE complexes were estimated to participate in entry, this yields total energies of 20 to 240 kbT released during the respective membrane fusion processes. In analogy, assuming a total energy of 40 to 120 kbT required for membrane fusion, our estimates that 2 to 7 trimers are required for HIV entry indicate that each trimer releases between 6 to 60 kbT during the entry process. Of note, the calculated total energies released by both HA trimers and SNARE complexes appear to be higher than the reported energy required for membrane fusion. This could potentially be due to inefficient coupling of the energy generated through protein conformational rearrangements into membrane deformation, or divergence between artificial membranes employed in biophysical experiments to measure membrane fusion energies and naturally occurring membranes containing proteins and having varying lipid composition. In sum, the strong agreement in the estimated energies across biological systems is intriguing and suggests that the overall energy requirements of membrane fusion and principles of energy elicitation by fusion proteins are closely related.

Our estimates that HIV strains typically require 2 to 7 trimers for entry are also consistent with the observations that env trimers cluster on virions and that HIV establishes a contact zone where several env-receptor pairings between virus and target cell are formed, the so-called “entry claw” [19], [28]. When defining molecular requirements for HIV entry, it is important to consider that envelope trimer activities may reach beyond solely providing the energy for membrane fusion. For example, binding of HIV trimers to their target cell receptors triggers an array of intracellular signals, which amongst other processes is thought to govern intracellular actin re-arrangements [79] and may be required to support membrane fusion and pore enlargement as previously proposed [10], [11].

In summary, our estimates of the HIV entry stoichiometry are in strong accordance with requirements found in other membrane fusion processes. Importantly, we show that capacities of individual HIV envelopes in mediating entry can vary substantially which is likely due to differences between trimers in soliciting energy required for membrane fusion. Our data strongly suggest that viruses overcome these envelope limitations by increasing the number of envelope-receptor pairings involved in the entry process. Hence, the stoichiometry of HIV entry is an important parameter steering virion infectivity and its assessment provides a relevant contribution towards a refined understanding of HIV-1 entry and pathogenesis. Knowledge obtained from the quantitative assessment of trimer-receptor interactions during HIV entry is a prerequisite in unravelling the stoichiometry of trimer interactions with target cell receptors or virus inactivation by neutralizing antibodies and entry inhibitors and thus may aid future approaches in HIV vaccine or entry inhibitor design.

Materials and Methods

Cells, viruses and inhibitors

293-T cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and TZM-bl cells [80] from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (NIH ARP). Both cell types were cultivated in DMEM (Gibco) containing 10% heat inactivated FCS and penicillin/streptomycin. Plasmids encoding the envelopes of strains JR-FL, SF162, NL4-3, RHPA, AC10, REJO, BG505 and ZM214 were obtained from the NIH ARP. Envelope ZA110 was described previously [67]. Envelope clone P3N [60] was a gift from Dr. Cecilia Cheng-Mayer, Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, New York, USA. Envelope clone CAP88 [81] was a gift from Dr. Lynn Morris, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa. All envelope point mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent QuikChange II XL) according to the manufacturer instructions. All point mutant envelopes were sequenced by in-house Sanger sequencing to confirm presence of the desired mutations and absence of unintended sequence changes. V1V2-deleted envelopes were previously described [67]. The Luciferase reporter HIV pseudotyping vector pNLLuc-AM was previously described [67]. T-20 [82] was purchased from Roche Pharmaceuticals.

Estimating the stoichiometry of virus entry by mixed trimer experiments

To estimate the stoichiometry of entry we employed a previously described approach [13]. To produce HIV-1 pseudotype virus stocks expressing mixed trimers with varying ratios of functional to dominant-negative env, 293-T cells in 12 well plates (100.000 cells per well in 1 ml complete DMEM, seeded 24 h pre-transfection) were transfected with 1.5 µg pNLLuc-AM and 0.5 µg env expression plasmids, using polyethyleneimine (PEI) as transfection reagent. The ratio of functional to dominant negative env expression plasmids was varied to yield combinations with 100, 90, 70, 50, 30, 10 and 0% of functional env. Total env plasmid content was always at 0.5 µg. After overnight incubation the transfection medium was replaced with 1 ml fresh complete DMEM and virus-containing supernatants were harvested 48 h post transfection. All mixed trimer combinations of an individual virus strain were always generated in parallel, excluding influences of producer cells and transfection procedure. To determine virus infectivity, serial dilutions of virus stocks starting with 100 µl of undiluted virus supernatant were added to TZM-bl reporter cells in 96-well plates (10.000 cells per well) in DMEM medium supplemented with 10 µg/ml DEAE-Dextran. TZM-bl infection was quantified 48 h post-infection by measuring activity of the firefly luciferase reporter. For each functional to dominant negative env ratio series, the infectivity of the stock containing 100% functional (wt) env was taken as reference (100% infectivity) and the relative infectivity of the stocks with increasing percentages of dominant-negative env were calculated in relation to that infectivity value. The resulting data of relative infectivity were plotted over the fraction of dominant-negative env of each stock and the data were analyzed with mathematical models [15] as described below.

Mathematical modeling of entry stoichiometry data

Mathematical model

Previously, we described mathematical models to analyze relative infectivity data generated with virions expressing mixed trimers [15]. Starting point of the mathematical modeling was a basic model, in which we made the following assumptions concerning the experimental system:

-

During the transfection of virus producer cells, the fraction of plasmids encoding wild-type, fwt, and mutant, fm, envelope proteins are identical inside and outside the cells, and the pool of produced envelope proteins inside the transfected cell reflects these fractions as well.

-

Envelope proteins assemble randomly into trimers. More precisely, the number of mutant envelope proteins in a trimer follows a Binomial-distribution with a trial parameter 3 and a success parameter fm.

-

Trimers can move freely on the viral surface, i.e. each functional trimer can potentially engage with cellular receptors to assist in mediating cell entry.

To verify the use of this model for our data analysis we assessed the validity of the underlying assumptions listed above. Pseudotyped virions are produced by transfecting cells with different plasmids encoding for env and the required structural and accessory HIV proteins. This co-transfection approach and the existence of heterotrimers in setups with plasmids encoding for different envelope proteins show that more than one plasmid can enter a virus producer cell. Thus, we conclude that sufficient numbers of plasmids enter transfected cells to guarantee that the envelope pool composition reflects the composition of plasmids encoding for the different envelope variants, i.e. assumption (i) is justified. Previous studies from others and us indicated that related env variants form randomly mixed trimers [13], [66], [67], [83], i.e. assumption (ii) is justified. Chojnacki et al. [28]showed that trimers on mature virions can move freely, i.e. assumption (iii) is also justified.

The model predicts the relative infectivity of a virion stock produced with a given fraction of mutant envelope proteins fm, the fraction of virions with s trimers, ηs 0≤s≤smax, and the stoichiometry of entry, T:

where p = (1−fm)3 is the probability that a trimer consist of only wild-type envelope proteins and is therefore functional. smax is the maximal number of trimers on a virion's surface. In the numerator we calculate the probability that a virion with s trimers can infect a cell, i.e. has at least T functional trimers (i.e. the expression in the squared brackets). This probability is weighted by the probability that a random virion has s trimers, ηs. All these probabilities are summed up for virions having at least T trimers. This expression is then divided by the probability that a random virion expressing only wildtype envelope proteins is infectious, because we normalize the measured infectivities accordingly in the experiments. For additional analyses of the relative infectivities we also employed model extensions described earlier [15]. In two model extensions we relaxed one of the assumptions (i) or (ii) as defined above and in a third model extension we implement an incremental increase of virus infectivity with trimer numbers. For a more detailed derivation of the RI-predictions predictions in the basic model and the different extensions please refer to [15].Trimer number distributions

The trimer number distribution is an important input parameter and the relative infectivity prediction is sensitive to changes in the trimer number distribution [15]. In our previous work, we based our estimations of the parameter T on discretized B-distributed trimer numbers with mean 14 and variance 49 as reported by counting trimers on the virion surface in cryo-electron microscopy experiments [26]. In the present study, we experimentally determined the mean trimer numbers of the 11 different viral strains included in our study (Table 1). However, our measurements do not allow inferring higher moments of the distribution of the trimer numbers, such as the variance. To overcome this problem, we calculated the trimer number distributions using the discretized B-distribution defined in [15] with the measured mean trimer numbers, μ (Table 1), and the variance calculated according to v = 49/14*μ [26]. The maximal trimer number, smax, was set to 100.

Analysis

To estimate T, we fitted the relative infectivity function to experimentally obtained relative infectivity values by assuming trimer number distributions calculated as described above applying a non-linear regression algorithm. Because relative infectivity data ranges from 0 to 1, the data was transformed with the arcsin-sqrt function. To gain an accuracy measure of our estimates, we perform a bootstrap procedure with 1000 replicates. All analyses were performed using the statistical software package R [84]. The corresponding code is available upon request.

Production of pseudotype virus stocks for infectivity assessment and entry kinetics

To produce HIV-1 pseudotype virus stocks for comparisons of virus infectivity and determination of virus entry kinetics, 293-T cells in T75 flasks (2.250.000 cells in 15 ml complete DMEM, seeded 24 h pre-transfection) were transfected with env and pNLLuc-AM plasmids (7.5 µg and 22.5 µg, respectively) using PEI as transfection reagent. The medium was exchanged 12 h post-transfection and virus-containing supernatants were harvested 48 h post-transfection. The supernatants were cleared by low speed centrifugation (300 g, 3 minutes), aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Virus infectivity was quantified on TZM-bl reporter cells as described above.

gp120 and p24 ELISA of pseudotype virus stocks

To determine gp120 and p24 content of HIV-1 pseudotype virus preparations, 293-T cells in T25 flasks (750.000 cells in 5 ml complete DMEM, seeded 24 h pre-transfection) were transfected with env and pNLLuc-AM plasmids (2.5 µg and 7.5 µg, respectively) using PEI as transfection reagent. The medium was exchanged 12 h post-transfection and virus-containing supernatants were harvested 48 h post-transfection. The supernatants were cleared by low speed centrifugation (300 g, 3 minutes), then ultracentrifugated (SW28 rotor, 2 h, 28.000 rpm, 4°C), the supernatant removed and viral pellets resuspended in 0.3 ml cold PBS and stored at −80°C. Virion associated p24 and gp120 antigens were quantified by ELISA as previously described [67]. Briefly, virus preparations were dissolved in 1% Empigen (Fluka Analytical, Buchs, Switzerland) and dilutions of each sample probed for gp120 and p24. Gp120 was captured on anti-gp120 D7324 (Aalto Bioreagents, Dublin, Ireland) coated immunosorbent plates and detected with biotinylated CD4-IgG2 and Streptavidin-coupled Alkaline Phosphatase (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK). P24 was captured on anti-p24 D7320 (Aalto Bioreagents, Dublin, Ireland) coated plated and detected using Alkaline Phosphatase-coupled antibody BC1071 (Aalto Bioreagents, Dublin, Ireland). Concentrations of gp120 and p24 in the samples were calculated in relation to standard curves obtained with gp120 and p24 proteins of known concentration. To derive virion numbers from p24 concentrations, we assumed 2000 (for the data in main manuscript and figures) or alternatively 2400 (S3B Fig.) p24 molecules per virion [23], [24], [33]. Trimers per virion were then calculated from the obtained gp120 concentration in relation to the number of virions per sample.

Virus entry kinetics

To determine virus entry kinetics, TZM-bl cells were seeded in 96-well plates (20.000 cells per well) in complete DMEM supplemented with 10 µg/ml DEAE-Dextran. 24 h post-seeding, cells were first cooled at 4°C for 5 minutes, then the medium was removed. HIV-1 pseudotype virus stocks adjusted to 50.000 RLU in 100 µl DMEM at 4°C were added per well and plates centrifuged for 70 minutes at 1200 g and 10°C. The low temperature was chosen to allow virus attachment during spinoculation but no entry. Following spinoculation the supernatant with unbound virus was removed and 130 µl of DMEM, pre-warmed to 37°C, were added per well to initiate infection (timepoint zero) and plates were incubated at 37°C. At defined timepoints post-infection, 20 µl of T-20 (375 µg/ml in DMEM; yielding a final assay concentration of 50 µg/ml) were added per well to stop the viral entry process. To obtain a measure for infectivity across different experiments, the wells with the last T-20 addition at 120 min after infection start were used as 100% reference infectivity value and the infectivity of all other T-20 treated wells were set in relation to it. In addition, a mock-treated well (addition of 20 µl DMEM at timepoint zero) was evaluated to assess absolute infectivity in absence of T-20.

PBMC infection experiments

Isolation and infection of PBMCs was performed as previously described [85]. Briefly, PBMCs were isolated from pooled buffy coat of 3 healthy blood donors, stimulated with anti-CD3 and PHA in presence of 100 U IL-2 for 2 days and then seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 100.000 cells per well in 100 µl RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FCS, antibiotics, 100 U IL-2 and 2.5 µg/ml (final assay concentration) polybrene. Serial dilutions of mixed trimer virus stocks (100 µl per well) were added to the PBMCs and cells were incubated at 37°C for 72 h before determining luciferase reporter activity.

Statistical analyses

Correlation analyses according to Pearson and multiple unpaired t-tests to derive the p-values for the comparisons of wt and V1V2-deleted envs were performed in GraphPad Prism 6.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KlassePJ (2012) The molecular basis of HIV entry. Cell Microbiol 14 : 1183–1192.

2. WilenCB, TiltonJC, DomsRW (2012) Molecular mechanisms of HIV entry. Adv Exp Med Biol 726 : 223–242.

3. MascolaJR, HaynesBF (2013) HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies: understanding nature's pathways. Immunol Rev 254 : 225–244.

4. KleinF, MouquetH, DosenovicP, ScheidJF, ScharfL, et al. (2013) Antibodies in HIV-1 vaccine development and therapy. Science 341 : 1199–1204.

5. PanceraM, ZhouT, DruzA, GeorgievIS, SotoC, et al. (2014) Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre-fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature. 2014 514(7523): 455–61.

6. PollakisG, PaxtonWA (2012) Use of (alternative) coreceptors for HIV entry. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 7 : 440–449.

7. BlumenthalR, DurellS, ViardM (2012) HIV entry and envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion. J Biol Chem 287 : 40841–40849.

8. HarrisonSC (2008) Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15 : 690–698.

9. CohenFS, MelikyanGB (2004) The energetics of membrane fusion from binding, through hemifusion, pore formation, and pore enlargement. J Membr Biol 199 : 1–14.

10. MelikyanGB (2008) Common principles and intermediates of viral protein-mediated fusion: the HIV-1 paradigm. Retrovirology 5 : 111.

11. JahnR, LangT, SudhofTC (2003) Membrane fusion. Cell 112 : 519–533.

12. GalloSA, ReevesJD, GargH, FoleyB, DomsRW, et al. (2006) Kinetic studies of HIV-1 and HIV-2 envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion. Retrovirology 3 : 90.

13. YangX, KurtevaS, RenX, LeeS, SodroskiJ (2005) Stoichiometry of envelope glycoprotein trimers in the entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 79 : 12132–12147.

14. KlassePJ (2007) Modeling how many envelope glycoprotein trimers per virion participate in human immunodeficiency virus infectivity and its neutralization by antibody. Virology 369 : 245–262.

15. MagnusC, RusertP, BonhoefferS, TrkolaA, RegoesRR (2009) Estimating the stoichiometry of human immunodeficiency virus entry. J Virol 83 : 1523–1531.

16. FloydDL, RagainsJR, SkehelJJ, HarrisonSC, van OijenAM (2008) Single-particle kinetics of influenza virus membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 15382–15387.

17. IvanovicT, ChoiJL, WhelanSP, van OijenAM, HarrisonSC (2013) Influenza-virus membrane fusion by cooperative fold-back of stochastically induced hemagglutinin intermediates. Elife 2: e00333.

18. DanieliT, PelletierSL, HenisYI, WhiteJM (1996) Membrane fusion mediated by the influenza virus hemagglutinin requires the concerted action of at least three hemagglutinin trimers. J Cell Biol 133 : 559–569.

19. SougratR, BartesaghiA, LifsonJD, BennettAE, BessJW, et al. (2007) Electron tomography of the contact between T cells and SIV/HIV-1: implications for viral entry. PLoS Pathog 3: e63.

20. KuhmannSE, PlattEJ, KozakSL, KabatD (2000) Cooperation of multiple CCR5 coreceptors is required for infections by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 74 : 7005–7015.

21. PlattEJ, DurninJP, ShindeU, KabatD (2007) An allosteric rheostat in HIV-1 gp120 reduces CCR5 stoichiometry required for membrane fusion and overcomes diverse entry limitations. J Mol Biol 374 : 64–79.

22. BurtonDR, PoignardP, StanfieldRL, WilsonIA (2012) Broadly neutralizing antibodies present new prospects to counter highly antigenically diverse viruses. Science 337 : 183–186.

23. ChertovaE, Bess JrJWJr, CriseBJ, SowderIR, SchadenTM, et al. (2002) Envelope glycoprotein incorporation, not shedding of surface envelope glycoprotein (gp120/SU), Is the primary determinant of SU content of purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol 76 : 5315–5325.

24. LayneSP, MergesMJ, DemboM, SpougeJL, ConleySR, et al. (1992) Factors underlying spontaneous inactivation and susceptibility to neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus. Virology 189 : 695–714.

25. ZhuP, ChertovaE, BessJJr, LifsonJD, ArthurLO, et al. (2003) Electron tomography analysis of envelope glycoprotein trimers on HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 : 15812–15817.

26. ZhuP, LiuJ, BessJJr, ChertovaE, LifsonJD, et al. (2006) Distribution and three-dimensional structure of AIDS virus envelope spikes. Nature 441 : 847–852.

27. LiuJ, BartesaghiA, BorgniaMJ, SapiroG, SubramaniamS (2008) Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature 455 : 109–113.

28. ChojnackiJ, StaudtT, GlassB, BingenP, EngelhardtJ, et al. (2012) Maturation-dependent HIV-1 surface protein redistribution revealed by fluorescence nanoscopy. Science 338 : 524–528.

29. LouderMK, SamborA, ChertovaE, HunteT, BarrettS, et al. (2005) HIV-1 envelope pseudotyped viral vectors and infectious molecular clones expressing the same envelope glycoprotein have a similar neutralization phenotype, but culture in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is associated with decreased neutralization sensitivity. Virology 339 : 226–238.

30. FreedEO, MyersDJ, RisserR (1989) Mutational analysis of the cleavage sequence of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein precursor gp160. J Virol 63 : 4670–4675.

31. GuoHG, VeroneseFM, TschachlerE, PalR, KalyanaramanVS, et al. (1990) Characterization of an HIV-1 point mutant blocked in envelope glycoprotein cleavage. Virology 174 : 217–224.

32. FreedEO, DelwartEL, BuchschacherGLJr, PanganibanAT (1992) A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 dominantly interferes with fusion and infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 : 70–74.

33. CarlsonLA, BriggsJA, GlassB, RichesJD, SimonMN, et al. (2008) Three-dimensional analysis of budding sites and released virus suggests a revised model for HIV-1 morphogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 4 : 592–599.

34. CaoJ, SullivanN, DesjardinE, ParolinC, RobinsonJ, et al. (1997) Replication and neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lacking the V1 and V2 variable loops of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol 71 : 9808–9812.

35. WyattR, SullivanN, ThaliM, RepkeH, HoD, et al. (1993) Functional and immunologic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins containing deletions of the major variable regions. J Virol 67 : 4557–4565.

36. StamatatosL, WiskerchenM, Cheng-MayerC (1998) Effect of major deletions in the V1 and V2 loops of a macrophage-tropic HIV type 1 isolate on viral envelope structure, cell entry, and replication. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 14 : 1129–1139.

37. PalmerC, BalfeP, FoxD, MayJC, FrederikssonR, et al. (1996) Functional characterization of the V1V2 region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology. United States pp 436–449.

38. BrandenbergOF, RusertP, MagnusC, WeberJ, BoniJ, et al. (2014) Partial rescue of V1V2 mutant infectivity by HIV-1 cell-cell transmission supports the domain's exceptional capacity for sequence variation. Retrovirology 11 : 75.

39. EganMA, CarruthLM, RowellJF, YuX, SilicianoRF (1996) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein endocytosis mediated by a highly conserved intrinsic internalization signal in the cytoplasmic domain of gp41 is suppressed in the presence of the Pr55gag precursor protein. J Virol 70 : 6547–6556.

40. YusteE, ReevesJD, DomsRW, DesrosiersRC (2004) Modulation of Env content in virions of simian immunodeficiency virus: correlation with cell surface expression and virion infectivity. J Virol 78 : 6775–6785.

41. PlattEJ, DurninJP, KabatD (2005) Kinetic factors control efficiencies of cell entry, efficacies of entry inhibitors, and mechanisms of adaptation of human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol 79 : 4347–4356.

42. PlattEJ, KozakSL, DurninJP, HopeTJ, KabatD (2010) Rapid dissociation of HIV-1 from cultured cells severely limits infectivity assays, causes the inactivation ascribed to entry inhibitors, and masks the inherently high level of infectivity of virions. J Virol 84 : 3106–3110.

43. MoorePL, RanchobeN, LambsonBE, GrayES, CaveE, et al. (2009) Limited neutralizing antibody specificities drive neutralization escape in early HIV-1 subtype C infection. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000598.

44. RaoM, PeachmanKK, KimJ, GaoG, AlvingCR, et al. (2013) HIV-1 Variable Loop 2 and its Importance in HIV-1 Infection and Vaccine Development. Curr HIV Res 11 : 427–438.

45. Los Alamos HIV database: HIV-1/SIVcpz curated alignment 2013.

46. WalkerLM, PhogatSK, Chan-HuiPY, WagnerD, PhungP, et al. (2009) Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science 326 : 285–289.

47. WibmerCK, BhimanJN, GrayES, TumbaN, Abdool KarimSS, et al. (2013) Viral escape from HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies drives increased plasma neutralization breadth through sequential recognition of multiple epitopes and immunotypes. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003738.

48. WuX, ChangelaA, O'DellS, SchmidtSD, PanceraM, et al. (2011) Immunotypes of a Quaternary Site of HIV-1 Vulnerability and Their Recognition by Antibodies. J Virol 85 : 4578–4585.

49. LuJ, DeeksSG, HohR, BeattyG, KuritzkesBA, et al. (2006) Rapid emergence of enfuvirtide resistance in HIV-1-infected patients: results of a clonal analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 43 : 60–64.

50. ReevesJD, LeeFH, MiamidianJL, JabaraCB, JuntillaMM, et al. (2005) Enfuvirtide resistance mutations: impact on human immunodeficiency virus envelope function, entry inhibitor sensitivity, and virus neutralization. J Virol 79 : 4991–4999.

51. EckertDM, KimPS (2001) Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu Rev Biochem 70 : 777–810.

52. RisseladaHJ, GrubmullerH (2012) How SNARE molecules mediate membrane fusion: recent insights from molecular simulations. Curr Opin Struct Biol 22 : 187–196.

53. ChernomordikLV, KozlovMM (2008) Mechanics of membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15 : 675–683.

54. LiuW, ParpuraV (2010) SNAREs: could they be the answer to an energy landscape riddle in exocytosis? ScientificWorldJournal 10 : 1258–1268.

55. GrafmullerA, ShillcockJ, LipowskyR (2009) The fusion of membranes and vesicles: pathway and energy barriers from dissipative particle dynamics. Biophys J 96 : 2658–2675.

56. MagnusC, RegoesRR (2011) Restricted occupancy models for neutralization of HIV virions and populations. J Theor Biol 283 : 192–202.

57. HaimH, StrackB, KassaA, MadaniN, WangL, et al. (2011) Contribution of Intrinsic Reactivity of the HIV-1 Envelope Glycoproteins to CD4-Independent Infection and Global Inhibitor Sensitivity. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002101.

58. Munro JB, Gorman J, Ma X, Zhou Z, Arthos J, et al.. (2014) Conformational dynamics of single HIV-1 envelope trimers on the surface of native virions. Science.

59. WhiteTA, BartesaghiA, BorgniaMJ, MeyersonJR, de la CruzMJ, et al. (2010) Molecular architectures of trimeric SIV and HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins on intact viruses: strain-dependent variation in quaternary structure. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001249.

60. HoSH, TascaS, ShekL, LiA, GettieA, et al. (2007) Coreceptor switch in R5-tropic simian/human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol 81 : 8621–8633.

61. MohrmannR, de WitH, VerhageM, NeherE, SorensenJB (2010) Fast vesicle fusion in living cells requires at least three SNARE complexes. Science 330 : 502–505.

62. ShiL, ShenQT, KielA, WangJ, WangHW, et al. (2012) SNARE proteins: one to fuse and three to keep the nascent fusion pore open. Science 335 : 1355–1359.

63. MagnusC, BrandenbergOF, RusertP, TrkolaA, RegoesRR (2013) Mathematical models: A key to understanding HIV envelope interactions? J Immunol Methods 398–399 : 1–18.

64. BourinbaiarAS (1994) The ratio of defective HIV-1 particles to replication-competent infectious virions. Acta Virol 38 : 59–61.

65. PoignardP, MoulardM, GolezE, VivonaV, FrantiM, et al. (2003) Heterogeneity of envelope molecules expressed on primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles as probed by the binding of neutralizing and nonneutralizing antibodies. J Virol 77 : 353–365.

66. SalzwedelK, BergerEA (2000) Cooperative subunit interactions within the oligomeric envelope glycoprotein of HIV-1: functional complementation of specific defects in gp120 and gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 : 12794–12799.

67. RusertP, KrarupA, MagnusC, BrandenbergOF, WeberJ, et al. (2011) Interaction of the gp120 V1V2 loop with a neighboring gp120 unit shields the HIV envelope trimer against cross-neutralizing antibodies. J Exp Med 208 : 1419–1433.

68. MagnusC, RegoesRR (2010) Estimating the Stoichiometry of HIV Neutralization. PLoS Comput Biol 6: e1000713.

69. FangQ, LindauM (2014) How Could SNARE Proteins Open a Fusion Pore? Physiology (Bethesda) 29 : 278–285.

70. MarkosyanRM, CohenFS, MelikyanGB (2003) HIV-1 envelope proteins complete their folding into six-helix bundles immediately after fusion pore formation. Mol Biol Cell 14 : 926–938.

71. LiF, PincetF, PerezE, EngWS, MeliaTJ, et al. (2007) Energetics and dynamics of SNAREpin folding across lipid bilayers. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14 : 890–896.

72. LiuW, MontanaV, ParpuraV, MohideenU (2009) Single Molecule Measurements of Interaction Free Energies Between the Proteins Within Binary and Ternary SNARE Complexes. J Nanoneurosci 1 : 120–129.

73. GaoY, ZormanS, GundersenG, XiZ, MaL, et al. (2012) Single reconstituted neuronal SNARE complexes zipper in three distinct stages. Science 337 : 1340–1343.

74. SinhaR, AhmedS, JahnR, KlingaufJ (2011) Two synaptobrevin molecules are sufficient for vesicle fusion in central nervous system synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 14318–14323.

75. MarkinVS, AlbanesiJP (2002) Membrane fusion: stalk model revisited. Biophys J 82 : 693–712.

76. KuzminPI, ZimmerbergJ, ChizmadzhevYA, CohenFS (2001) A quantitative model for membrane fusion based on low-energy intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 : 7235–7240.

77. KozlovMM, ChernomordikLV (1998) A mechanism of protein-mediated fusion: coupling between refolding of the influenza hemagglutinin and lipid rearrangements. Biophys J 75 : 1384–1396.

78. WiederholdK, FasshauerD (2009) Is assembly of the SNARE complex enough to fuel membrane fusion? J Biol Chem 284 : 13143–13152.

79. SpearM, GuoJ, WuY (2012) The trinity of the cortical actin in the initiation of HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology 9 : 45.

80. WeiX, DeckerJM, LiuH, ZhangZ, AraniRB, et al. (2002) Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46 : 1896–1905.

81. MoorePL, RanchobeN, LambsonBE, GrayES, CaveE, et al. (2009) Limited neutralizing antibody specificities drive neutralization escape in early HIV-1 subtype C infection. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000598.

82. WildC, GreenwellT, MatthewsT (1993) A synthetic peptide from HIV-1 gp41 is a potent inhibitor of virus-mediated cell-cell fusion. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 9 : 1051–1053.

83. YangX, KurtevaS, LeeS, SodroskiJ (2005) Stoichiometry of antibody neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 79 : 3500–3508.

84. Team RC (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

85. MannAM, RusertP, BerlingerL, KusterH, GunthardHF, et al. (2009) HIV sensitivity to neutralization is determined by target and virus producer cell properties. AIDS 23 : 1659–1667.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Differential Reliance on Autophagy for Protection from HSV Encephalitis between Newborns and AdultsČlánek The Molecular Basis for Control of ETEC Enterotoxin Expression in Response to Environment and HostČlánek Preferential Use of Central Metabolism Reveals a Nutritional Basis for Polymicrobial Infection

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 1- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The Importance of Pathogen Load

- Implication of Gut Microbiota in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- Infections in Humans and Animals: Pathophysiology, Detection, and Treatment

- Helminth-Induced Immune Regulation: Implications for Immune Responses to Tuberculosis

- The M3 Muscarinic Receptor Is Required for Optimal Adaptive Immunity to Helminth and Bacterial Infection

- An Iron-Mimicking, Trojan Horse-Entering Fungi—Has the Time Come for Molecular Imaging of Fungal Infections?

- Modulates the Unfolded Protein Response in during Infection

- Differential Reliance on Autophagy for Protection from HSV Encephalitis between Newborns and Adults

- Identification of HNRNPK as Regulator of Hepatitis C Virus Particle Production

- Parasite Biomass-Related Inflammation, Endothelial Activation, Microvascular Dysfunction and Disease Severity in Vivax Malaria

- : Trypanosomatids Adapted to Plant Environments

- Early Virus-Host Interactions Dictate the Course of a Persistent Infection

- TLR3 Signaling in Macrophages Is Indispensable for the Protective Immunity of Invariant Natural Killer T Cells against Enterovirus 71 Infection

- The Epstein-Barr Virus Encoded BART miRNAs Potentiate Tumor Growth

- Macrophage-Derived Human Resistin Is Induced in Multiple Helminth Infections and Promotes Inflammatory Monocytes and Increased Parasite Burden

- Dissemination of a Highly Virulent Pathogen: Tracking The Early Events That Define Infection

- Variability in Tuberculosis Granuloma T Cell Responses Exists, but a Balance of Pro- and Anti-inflammatory Cytokines Is Associated with Sterilization

- The Shear Stress of Host Cell Invasion: Exploring the Role of Biomolecular Complexes

- The Molecular Basis for Control of ETEC Enterotoxin Expression in Response to Environment and Host

- Different Infectivity of HIV-1 Strains Is Linked to Number of Envelope Trimers Required for Entry

- Secreted Herpes Simplex Virus-2 Glycoprotein G Modifies NGF-TrkA Signaling to Attract Free Nerve Endings to the Site of Infection

- Preferential Use of Central Metabolism Reveals a Nutritional Basis for Polymicrobial Infection

- A New Family of Secreted Toxins in Pathogenic Neisseria Species

- A Human Type 5 Adenovirus-Based Therapeutic Vaccine Re-programs Immune Response and Reverses Chronic Cardiomyopathy

- Regulation of Oncogene Expression in T-DNA-Transformed Host Plant Cells

- GITR Intrinsically Sustains Early Type 1 and Late Follicular Helper CD4 T Cell Accumulation to Control a Chronic Viral Infection

- Cell Cycle-Independent Phospho-Regulation of Fkh2 during Hyphal Growth Regulates Pathogenesis

- Virus-Induced NETs – Critical Component of Host Defense or Pathogenic Mediator?

- Environmental Drivers of the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in the United States

- Protective Efficacy of Centralized and Polyvalent Envelope Immunogens in an Attenuated Equine Lentivirus Vaccine

- Transmitted Virus Fitness and Host T Cell Responses Collectively Define Divergent Infection Outcomes in Two HIV-1 Recipients

- Systemic Expression of Kaposi Sarcoma Herpesvirus (KSHV) Vflip in Endothelial Cells Leads to a Profound Proinflammatory Phenotype and Myeloid Lineage Remodeling

- Dengue Virus RNA Structure Specialization Facilitates Host Adaptation

- DNA Is an Antimicrobial Component of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps

- Uropathogenic Superinfection Enhances the Severity of Mouse Bladder Infection

- Well-Ordered Trimeric HIV-1 Subtype B and C Soluble Spike Mimetics Generated by Negative Selection Display Native-like Properties