-

Články

Reklama

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

ReklamaSimultaneous Disruption of Two DNA Polymerases, Polη and Polζ, in Avian DT40 Cells Unmasks the Role of Polη in Cellular Response to Various DNA Lesions

Replicative DNA polymerases are frequently stalled by DNA lesions. The resulting replication blockage is released by homologous recombination (HR) and translesion DNA synthesis (TLS). TLS employs specialized TLS polymerases to bypass DNA lesions. We provide striking in vivo evidence of the cooperation between DNA polymerase η, which is mutated in the variant form of the cancer predisposition disorder xeroderma pigmentosum (XP-V), and DNA polymerase ζ by generating POLη−/−/POLζ−/− cells from the chicken DT40 cell line. POLζ−/− cells are hypersensitive to a very wide range of DNA damaging agents, whereas XP-V cells exhibit moderate sensitivity to ultraviolet light (UV) only in the presence of caffeine treatment and exhibit no significant sensitivity to any other damaging agents. It is therefore widely believed that Polη plays a very specific role in cellular tolerance to UV-induced DNA damage. The evidence we present challenges this assumption. The phenotypic analysis of POLη−/−/POLζ−/− cells shows that, unexpectedly, the loss of Polη significantly rescued all mutant phenotypes of POLζ−/− cells and results in the restoration of the DNA damage tolerance by a backup pathway including HR. Taken together, Polη contributes to a much wide range of TLS events than had been predicted by the phenotype of XP-V cells.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001151

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001151Summary

Replicative DNA polymerases are frequently stalled by DNA lesions. The resulting replication blockage is released by homologous recombination (HR) and translesion DNA synthesis (TLS). TLS employs specialized TLS polymerases to bypass DNA lesions. We provide striking in vivo evidence of the cooperation between DNA polymerase η, which is mutated in the variant form of the cancer predisposition disorder xeroderma pigmentosum (XP-V), and DNA polymerase ζ by generating POLη−/−/POLζ−/− cells from the chicken DT40 cell line. POLζ−/− cells are hypersensitive to a very wide range of DNA damaging agents, whereas XP-V cells exhibit moderate sensitivity to ultraviolet light (UV) only in the presence of caffeine treatment and exhibit no significant sensitivity to any other damaging agents. It is therefore widely believed that Polη plays a very specific role in cellular tolerance to UV-induced DNA damage. The evidence we present challenges this assumption. The phenotypic analysis of POLη−/−/POLζ−/− cells shows that, unexpectedly, the loss of Polη significantly rescued all mutant phenotypes of POLζ−/− cells and results in the restoration of the DNA damage tolerance by a backup pathway including HR. Taken together, Polη contributes to a much wide range of TLS events than had been predicted by the phenotype of XP-V cells.

Introduction

DNA replication involves a rapid but fragile enzymatic mechanism that is frequently stalled by damage in the DNA template. To complete DNA replication, DNA lesions are bypassed by specialized DNA polymerases, a process called translesion synthesis (TLS) (reviewed in [1], [2]). A number of TLS polymerases, including Polη and Polζ, that are conserved throughout eukaryotic evolution, have been identified in yeast and mammals. Polη deficiency is responsible for a variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum (XP-V) [3], [4] that is characterized by UV photosensitivity and a predisposition to skin cancer (reviewed in [5]). Deficiency in Rev3, the catalytic subunit of Polζ, results in a considerably more severe phenotype, compared with Polη. In fact, Rev3 disruption is lethal to mouse embryogenesis [6]. Chicken DT40 cells deficient in Rev3 exhibit significant chromosome instability and hypersensitivity to a wide variety of DNA-damaging agents [7]–[10]. In addition to their role in TLS, both Polη and Polζ can contribute to homologous DNA recombination (HR) in DT40 cells [9], [11], [12].

Exposure to UV induces cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and 6-4 UV photoproducts in DNA. While Polη can efficiently and accurately bypass CPDs [4], [13]–[15], no single DNA polymerase has been shown to be capable of effectively bypassing 6-4 UV photoproducts in vitro. This suggests that the coordinate use of more than one polymerase is required to bypass such damage in vivo. In support of this notion, several biochemical studies have suggested that lesion bypass can be effected by two sequential nucleotide incorporation events [16], [17]. For example, to bypass the 6-4 UV photoproduct, Polη inserts a nucleotide opposite the damage as a first step, followed by extension from the inserted nucleotide as a second step. This extension process has been shown to be catalyzed by yeast Polζ and by human Polκ [1], [2], [18]. The contribution of mammalian Polζ to the extension step remains elusive, because functional Polζ has not been purified [19], [20]. Recently, replication of episomal plasmid DNA carrying various lesions was analyzed in mammalian cell lines to define the role of each DNA polymerase in TLS past individual DNA lesions [15], [21], [22]. Shachar et al. suggest the sequential usage of Polη and Polζ in TLS past the cisPt-GG lesion [21], while results of others do not support this two-step TLS model [15], [23]. Indeed, evidence for the two-step model in the replication of chromosomal DNA has so far been lacking. By contrast, both human and yeast Polη can bypass CPDs effectively in vitro without extension polymerases [4].

Combining genetic tractability with a number of sensitive phenotypic assays, the chicken DT40 B lymphocyte cell line provides a unique opportunity to precisely analyze the role of individual DNA polymerases in TLS as well as in HR. The immunoglobulin loci of DT40 cells undergo constitutive diversification in culture by a combination of gene conversion (which depends on HR) and point mutation (which depends on TLS [24]). This diversification is driven by activation-induced deaminase (AID) [25], [26], which catalyzes the deamination of cytosine to generate uracil in the immunoglobulin loci. The uracil is then eliminated by uracil glycosylase to form abasic sites, which are thought to be the lesions that trigger bypass, either by gene conversion or by mutagenic translesion synthesis (reviewed in [27]). To study TLS in a different context, an episomal plasmid-based system was recently developed to examine the replication of a plasmid carrying site-specific lesions, in this case 6-4 UV photoproducts, in DT40 cells [28].

To investigate the functional interaction between Polη and Polζ in the DT40 cell line, we created POLη−/−/POLζ−/− DT40 cells (hereafter called polη/polζ cells). Unexpectedly, depletion of Polη in the polζ cells suppressed virtually all mutant phenotypes associated with the loss of Polζ, including genome instability and hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. Furthermore, the reconstitution of POLη−/−/POLζ−/− cells with intact human Polη, but not the polymerase-deficient mutant carrying D115A/E116A substitutions, increased their hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents to the level of the POLζ−/− cells, indicating that Polη-dependent DNA synthesis is toxic in the absence of Polζ. Remarkably, this alleviation of the polζ phenotype was associated with the restoration of effective translesion synthesis. These data provide in vivo support for the two-step model of lesion bypass, with Polζ playing a critical role in the extension step following nucleotide incorporation by Polη.

Results

Deletion of Polη reversed the hypersensitivity of the polζ mutant to UV, ionizing radiation, MMS, and cisplatin

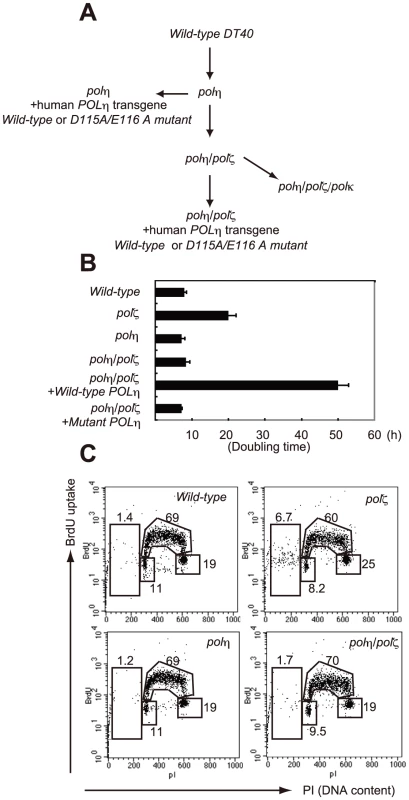

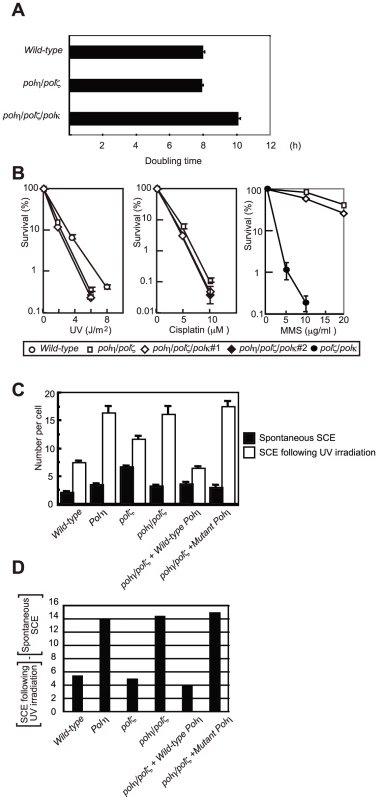

We generated polη/polζ cells by inactivating both REV3 alleles of the polη DT40 cells using a previously published gene-targeting strategy (Figure 1A) [9], [12]. The growth properties of the mutant cells were examined by measuring their growth rate and cell-cycle profile. As reported previously, the polη cells had a normal growth rate, whereas the polζ cells proliferated more slowly, exhibiting an increase in the sub-G1 fraction, indicative of spontaneous cell death during the cell cycle (Figure 1C). The loss of Polζ caused a significant increase in the number of spontaneous arising γH2AX foci, which represent replication collapse (Figure S1). Interestingly, deletion of POLη in the polζ cells reversed their growth retardation and reduced the rate of cell death (Figure 1B and 1C). Similarly, the number of spontaneous chromosomal aberrations was significantly reduced in polη/polζ cells, compared with polζ cells (Table 1). Ectopic expression of human Polη in polη/polζ cells diminished their growth rate to the level of polζ cells. This observation does not reflect general toxicity of the overexpressed human Polη, since its ectopic expression caused pronounced growth retardation only in the polη/polζ double mutant but not in wild-type cells (Figure S2). These observations indicate that the growth defect of polζ cells is dependent on the presence of Polη.

Fig. 1. Proliferation of chicken DT40 polζ, polη, and polη/polζ cells.

(A) Schematic representation of the generation of the mutant cells used in this study. (B) The polη and polη/polζ mutants grew more rapidly than did the polζ cells. Cells were cultured for 3 days. The doubling time of each mutant is shown. Note that wild-type cells divide every 8 hours. “+Wild-type POLη” represents a reconstitution of polη/polζ cells with wild-type human polη. “Mutant POLη” carries D115A/E116A mutations, which inactivate the polymerase activity of human Polη. Error bars show the SD of the mean for three independent assays. (C) Representative asynchronous flow cytometric cell-cycle profiles of wild-type, polη polζ, and polη/polζ cells. Cells were pulse-labeled with BrdU for 10 minutes and stained with propidium iodide (PI) to measure DNA content. The large gate on the left of each panel indicates the sub-G1 apoptotic cell fraction. The lower left, arch, and lower right gates indicate cells in the G1, S and G2/M phase, respectively. Numbers show the percentage of cells falling in each gate. Tab. 1. Frequency of spontaneous chromosomal aberrations in wild-type, polζ, polη, and polη/polζ double mutants.*

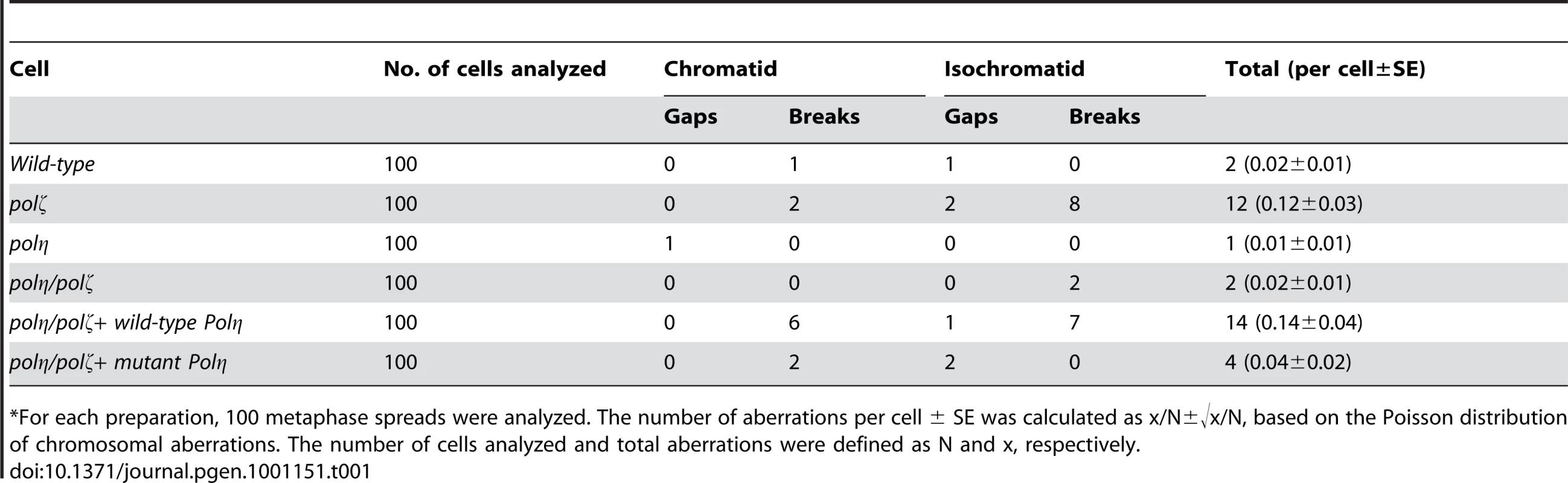

*For each preparation, 100 metaphase spreads were analyzed. The number of aberrations per cell ± SE was calculated as x/N±√x/N, based on the Poisson distribution of chromosomal aberrations. The number of cells analyzed and total aberrations were defined as N and x, respectively. The sensitivity of polη/polζ cells to genotoxic stresses was evaluated using a colony formation assay. polη cells showed a mild sensitivity to UV but not to the other genotoxic stresses, in agreement with the phenotype of mammalian XP-V cells [29], [30]. In contrast, polζ cells showed a marked sensitivity to UV, ionizing radiation, cis-diaminedichloroplatinum-II (cisplatin), and methylmethane sulfonate (MMS) (Figure 2), as previously described [9]. The polη/polζ mutant cells were less sensitive to UV than were the polζ cells. Furthermore, this double mutant showed significantly increased tolerance to ionizing radiation, cisplatin, and MMS, compared with the polζ cells. This increased tolerance of the polη/polζ cells was reversed by ectopic expression of human Polη. To investigate whether this reversion depended on the polymerase activity of human Polη, we expressed human POLη cDNA carrying D115A/E116A mutations in the polη/polζ cells. These mutations in the catalytic site abolish polymerase activity (data not shown), as previously reported in yeast [31]. The expression of the mutant Polη had no effect on the sensitivity of the polη/polζ cells to the DNA-damaging agents (Figure 2), indicating that Polη-dependent DNA synthesis sensitizes polζ cells to these DNA-damaging agents.

Fig. 2. Increased tolerance of polη/polζ cells to various genotoxic stresses, compared with polζ cells.

Colony survival of the indicated genotypes following the indicated genotoxic stresses. Data for the polη/polζ #1 clone are shown in the other figures. Error bars show the SD of the mean for three independent assays. polζ cells have a more prominent defect in TLS past abasic site than polη/polζ cells

We wished to investigate if Polη and Polζ could collaborate in TLS past specific types of DNA damage. To this end, we performed two sets of experiments: analysis of immunoglobulin hypermutation, which in DT40 provides a readout of the bypass of abasic sites [24], and analysis of the replication of a T-T (6-4) photoproduct on an episomal plasmid [28].

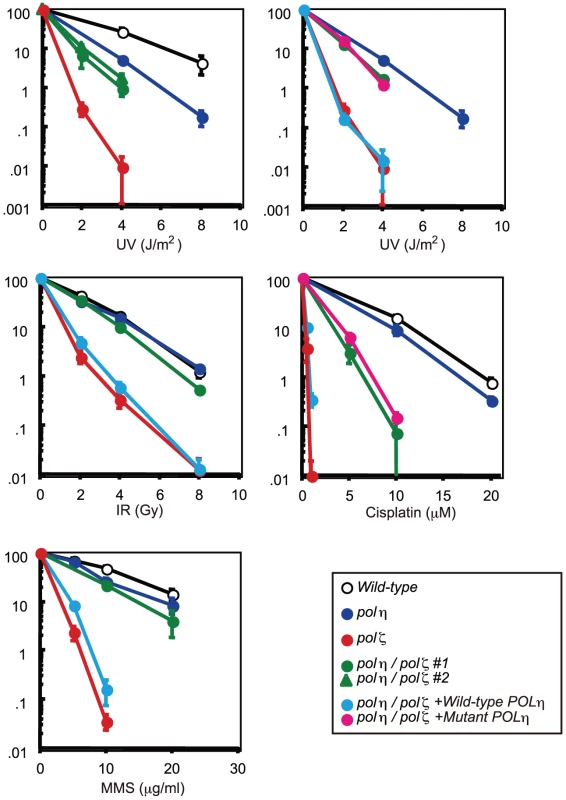

To induce Ig hypermutation, we overproduced AID in DT40 cells using a retrovirus vector [32], [33]. This vector drives the monocistronic expression of AID and green fluorescent protein (GFP), allowing a comparative assessment of the level of ectopic AID expression. At 24 hours after infection with the AID retrovirus, virtually all cells from each line displayed a strong GFP signal, indicating that the deficiency of Polη and Polζ did not affect the expression of AID (Figure 3A). However, a substantial fraction of the polζ cells died at day 3, and with the surviving polζ cells at day 10 showed a decrease level of GFP signals (Figure 3A and 3B). Furthermore, polζ cells, but not polη or polη/polζ cells, displayed prominent chromosomal breaks at day 3 post-infection (Figure 3C). Since the break sites on the chromosome were randomly distributed, the overexpressed AID protein may be targeting a number of different loci in addition to the Ig locus, in DT40 cells. These observations suggest that TLS past abasic sites created by the combined action of AID and uracil glycosylase may be performed less effectively in polζ cells, compared with polη/polζ or polη cells, resulting in chromosome breakage and cell death.

Fig. 3. polζ cells, but not polη or polη/polζ cells, are hypersensitive to AID overexpression.

(A) Reduced AID transgene expression over time in polζ cells. The expression of AID was estimated by measuring the intensity of the GFP signal. Filled and open distributions represent GFP intensity at days 1 and 10 post-infection, respectively. (B) Accumulation of dead cells in the polζ mutant population 3 days after the AID virus infection. The dot plot shows cells stained with PI. The percentage of dead cells falling into the indicated gate is shown in the histogram. (C) Chromosomal aberrations are induced by AID overexpression in polζ mutants. At day 3 post-infection, chromosomal aberrations in mitotic cells of the indicated genotype were analyzed. Fifty metaphase spreads were measured. The number of aberrations per cell ± SE was calculated as x/N±√x/N, where N and x are the numbers of cells analyzed and total aberrations, respectively. To verify that Polη-dependent DNA synthesis was toxic to the AID-overproducing polζ cells, we reconstituted polη/polζ cells with either wild-type POLη or the catalytically inactive mutant polηD115A/E116A). Wild-type POLη expression sensitized the polη/polζ cells to the overexpression of AID, whereas the mutant POLη had no impact on cell survival (Figure 3A and 3B). We thus conclude that, in polζ cells, TLS past abasic sites may be less effective because neither Polη nor any other polymerase can extend DNA synthesis following the Polη-mediated insertion of nucleotides opposite the abasic site.

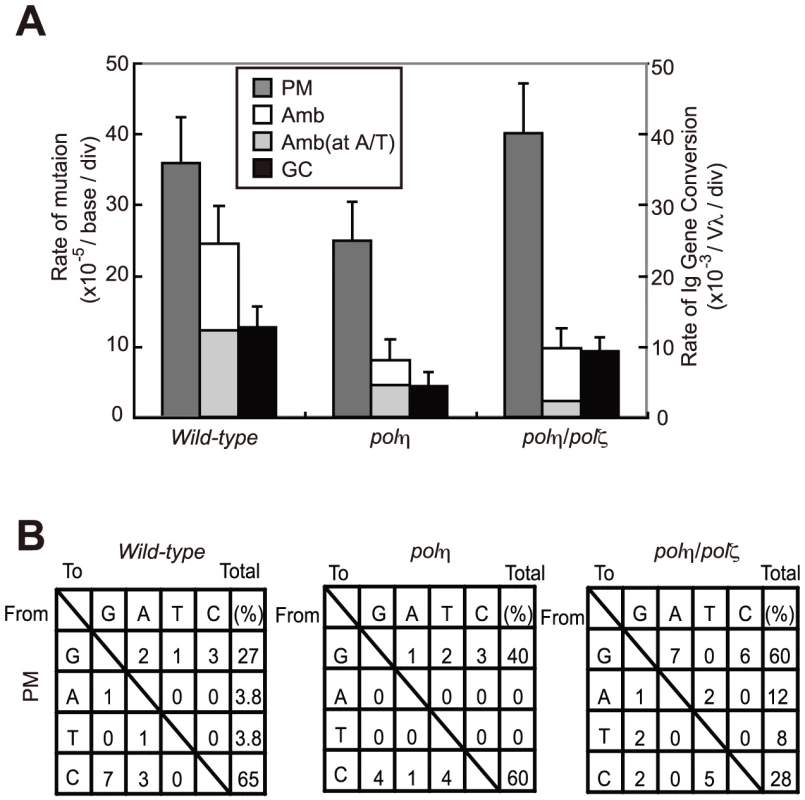

We have shown that AID overexpression results in increased TLS-mediated hypermutation at G/C base pairs in Ig V segments [32]. To define the role of Polη and Polζ in this TLS process, we determined the Ig Vλ nucleotide sequences of AID-overexpressing wild-type, polη, and polη/polζ cells. polζ cells were not analyzed because of the difficulty of ectopically expressing AID to the same extent as in the other lines. The number of non-templated point mutations (PM, Figure 4A) was somewhat lower in polη cells than in wild-type cells (This slight reduction is not significant (p = 0.15, t-test) [32]). Surprisingly, the level of Ig V mutations in polη/polζ cells was comparable to that of wild-type cells. This observation is in marked contrast with the fact that Rev1, an essential factor for the function of Polζ [20], plays a critical role in non-templated point mutations at the abasic site [34]. Moreover, Polζ played the critical role in cellular tolerance to AID-mediated abasic sites (Figure 3). These observations indicate that in the absence of both Polη and Polζ, other unidentified DNA polymerase(s) can participate in TLS past the abasic site. As the polη/polζ cells displayed a significant increase in the proportion of G/C to A/T transitions in the non-templated Ig V mutations (12/25; 48%), compared with wild-type cells (2/18; 11%)(Figure 4B), this unidentified DNA polymerase(s) may preferentially incorporate adenine opposite the abasic site in the absence of both Polη and Polζ.

Fig. 4. TLS–dependent point mutations in Ig V occur with comparable frequency in wild-type and polη/polζ cells.

(A) Rate of non-templated single-base substitutions (PM), ambiguous single base substitutions (Amb) (which are single base changes that have a potential donor sequence in the pseudogene array), and bona fide gene conversion tracts (GC) in the AID-virus-infected wild-type, polη, and polη/polζ DT40 cells shown in Figure 3. Cells were clonally expanded for two weeks. Three clones were analyzed in each data set. Note that the Amb mutation at A/T pairs represents short-tract gene conversion [32]. (B) Nucleotide substitution preferences (as a percentage of the indicated number in the total mutations) deduced from the Vλ sequence analysis of the clones shown in (A). The preferences are shown for mutations categorized as non-templated base substitutions (PM), which are caused by TLS past abasic sites [32]. Lack of TLS past the T-T (6-4) UV photoproduct in polζ cells is reversed by the inactivation of Polη

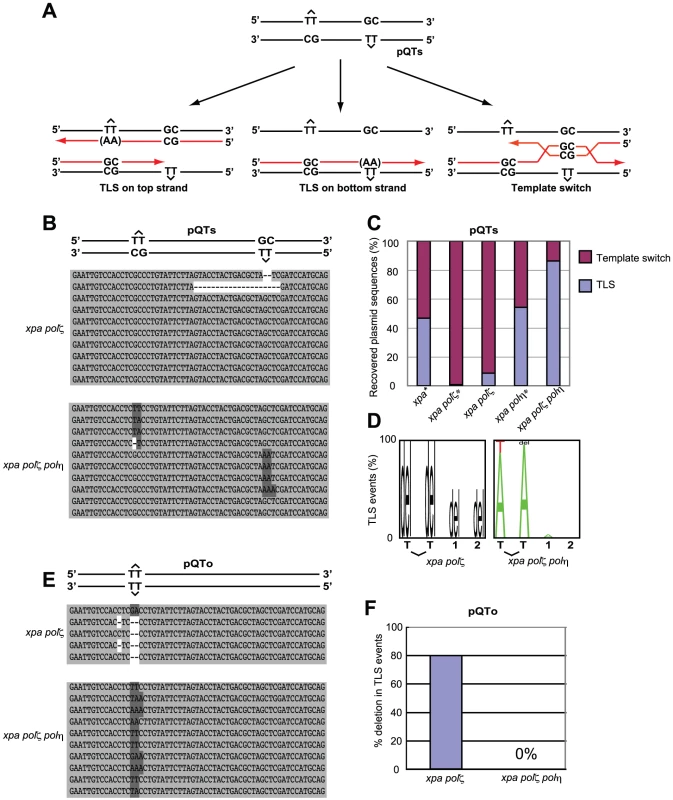

T-T (6-4) UV photoproducts represent the most formidable challenge to DNA replication, as they potently arrest replicative polymerases [35]. To analyze TLS past a T-T (6-4) photoproduct, we transfected two plasmids, pQTs and pQTo, [28] (Figure 5) carrying T-T (6-4) UV photoproducts into DT40 cells. At two days after transfection we recovered only replicated copies, and were thus able to analyze the replication of site-specific T-T (6-4) UV photoproducts in vivo. This photoproduct can be arranged in one of two ways. In the staggered conformation (pQTs) (Figure 5A), the lesions are separated by 28 intervening nucleotides and placed opposite a GpC mismatch. Replicated copies can thus result from TLS on the top or bottom strand. Error-free template switching should result in GpC at the site of the photoproduct, while TLS past this photoproduct may insert ApA (accurate TLS) or other nucleotides (inaccurate TLS) at this site. Note that our experiment was done in a nucleotide-excision repair-deficient (xpa-deficient) background, and thus excluded the recovery of replicated copies generated by error-free nucleotide-excision repair. In the second, unphysiological, replication template, the lesions are placed opposite to each other (pQTo) (Figure 5E). Using this conformation, replicated DNA copies can be recovered as a consequence of TLS, but not by template switching.

Fig. 5. TLS past a T-T (6-4) UV photoproduct on episomal plasmid DNA.

(A) Schematic of the staggered arrangement of T–T (6–4) UV photoproducts in the construct pQTs. The dinucleotide GC is placed opposite each lesion, and there are 28 bp between the lesions, with the possible outcomes of DNA replication over the area. TLS may occur on either the top or the bottom strand, with the most common base insertion shown as AA. Alternatively, the nascent strand of the sister chromatid may be used as an alternative undamaged template; one possible mechanism for such a template switching illustrated. (B) Example sequences of replicated pQTs plasmids recovered from xpa/polζ and xpa/polη/polζ clones, aligned with a schematic drawing of pQTs. TLS on the top strand (inserting mostly AA in the reverse direction, top set), TLS on the bottom strand (middle set), and error-free bypass (bottom set) are shown. Proportions are not representative. (C) The proportion of TLS versus error-free bypass in pQTs sequences recovered from xpa/polζ and xpa/polη/polζ cells, shown as a percentage of the total. Data shown with asterisks are taken from Szüts et al. [28]. A total of 23 and 29 sequences from xpa/polζ and xpa/polη/polζ cells, respectively, are shown as the sum of three independent experiments. (D) The pattern of nucleotide incorporation opposite the T-T (6-4) photoproduct in xpa/polζ and xpa/polη/polζ cells. Error-free pQTs sequences were excluded from analysis. The percentage of each nucleotide incorporated at each position is indicated by the size of the letter of the nucleotide in the column. del = deletion. The incorporation positions indicated are at the 3′ T and the 5′ T of the lesion, followed by the next two bases in the template, indicated by 1 and 2. (E) Example sequences of replicated pQTo plasmids recovered from xpa/polζ and xpa/polη/polζ clones, aligned with a schematic drawing of pQTo. (F) The frequency of replication associated with two or more nucleotide deletions in replicated copies of pQTo, which contains T–T (6–4) UV photoproducts in the opposing arrangement. To assess the mode of bypass used when generating replicated copies of pQTs, we analyzed the nucleotide sequences of replicated copies of plasmids recovered from DT40 cells (Figure 5B) and determined the proportion of TLS relative to error-free template switching (Figure 5C). Overall replication efficiency was comparable among cells carrying the various genotypes used in the previous study and this study. Previous study found that 45% and 55% of the recovered plasmid copies resulted from TLS in xpa and xpa/polη cells, respectively [28]. In comparison, the efficiency of TLS in xpa/polζ cells was significantly reduced, with less than 10% of the recovered plasmid generated as a consequence of TLS. All TLS events observed in the xpa/polζ cells were associated with deletion at damaged sites (Figure 5D). Thus, as found previously [28] (Figure 5C), we conclude that Polζ is required for the successful bypass of T-T (6-4) UV photoproducts by TLS. Remarkably, the xpa/polη/polζ cells displayed a normal TLS efficiency, indicating that the failure of TLS in polζ cells is dependent on the presence of Polη.

We also classified the replication products obtained from the pQTo plasmid, where bypass can be effected only by TLS or deletion. As found in the previous study [28], the loss of Polζ was frequently associated with the deletion of two or more nucleotides covering the site of the T-T (6-4) UV photoproduct (Figure 5E and 5F). The loss of Polζ did not impair TLS in the absence of Polη, but severely compromised it in the presence of Polη. A possible explanation, discussed below, is that the Polη-dependent insertion of nucleotides opposite the T-T (6-4) UV photoproduct inhibits the completion of TLS in the absence of Polζ (presumably due to defective extension from inserted nucleotides), while other unidentified DNA polymerases can perform the complete TLS reaction in polη/polζ cells.

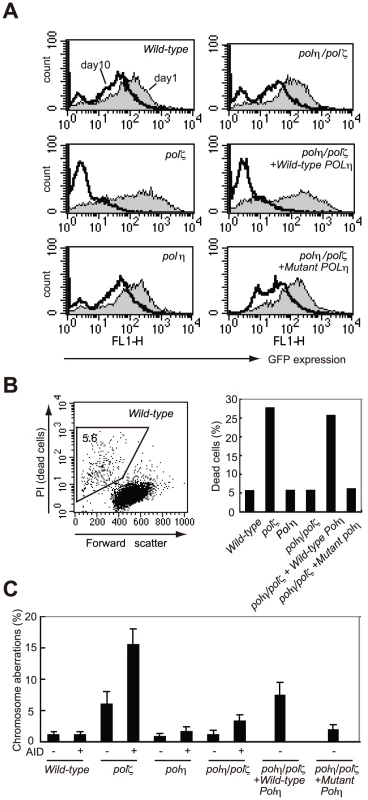

Polκ plays only a minor role in the damage tolerance of polη/polζ cells

The milder phenotype of the polη/polζ cells, compared with polζ single mutants, led us to investigate the contribution of other TLS polymerases to TLS in polη/polζ cells. We previously showed that polκ/polζ cells show a higher sensitivity to mono-alkylating agents, compared with polζ cells, though polκ cells show normal sensitivity [36], and thereby suggested that Polκ can partially substitute for the loss of Polζ. We therefore sought to determine whether Polκ contributes to damage tolerance in polη/polζ cells. To this end, we deleted the Polκ gene in polη/polζ cells and analyzed the phenotype of the resulting triple knockout polη/polκ/polζ clones (Figure 6A). Deletion of the Polκ gene tended to reduce growth kinetics. However, the polη/polκ/polζ clones exhibited only limited increase in DNA-damage sensitivity, compared with polη/polζ cells (Figure 6B). Likewise, overexpression of chicken Polκ did not increase cisplatin tolerance in polζ or polη/polζ cells (data not shown). These observations imply that Polκ does not play an important role in TLS in polη/polζ cells.

Fig. 6. HR, but not Polκ, contributes to increased cellular tolerance to DNA damage in polη/polζ cells, compared with polζ cells.

(A) Growth of polη/polζ and polη/polζ/polκ clones. Cells were cultured for 3 days. The doubling time of each mutant is shown. Error bars show the SD of the mean for three independent assays. (B) Sensitivity profiles of indicated mutant cells to UV and cisplatin. Error bars show the SD of the mean for three independent assays. (C) Induction of SCE in polη, polζ, and polη/polζ cells by UV. Cells were labeled with BrdU during over cell-cycles with or without UV irradiation (0.25 J/m2) before labeling. Spontaneous and induced SCEs in the macrochromosomes of 50 metaphase cells were counted. Histograms show the frequency of cells with the indicated numbers of SCEs per cell. The mean number of SCEs per cell ± SE is shown. Statistical significance was further calculated by the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. (D) The number of UV-induced SCE was calculated by subtracting spontaneous SCE from SCE following UV irradiation. polη/polζ cells, but not polζ cells, displayed increased numbers of UV-induced sister chromatid exchange events

Replication arrest can be released by two major mechanisms: HR and TLS [37]. HR-dependent release is initiated by homologous pairing between the 3′ end of the arrested strand and the sister chromatid, followed by strand invasion and DNA synthesis to extend the invading 3′ strand (Figure 7D). To analyze the efficiency of HR-mediated release from replication blockage, we analyzed sister chromatid exchange (SCE) (Figure 6C and 6D) [38], [39]. The level of SCE is likely to be determined by two factors: the number of DNA lesions that cause a replication block and the efficiency of HR-dependent release from replication blockage. As previously reported [9], [39], the level of spontaneous SCE was slightly increased (1.5 to 2-fold) in all TLS mutants compared with wild-type cells, presumably because lesions are more frequently channeled to HR. The polη cells displayed a markedly greater increase in the level of UV-induced SCE (the number of spontaneous SCE subtracted from the number of SCE following UV irradiation shown in Figure 6D), which phenotype is attributable to defective TLS over UV-induced damage. In contrast, in the polζ cells, the UV-induced SCE level was similar to that of wild-type cells, suggesting that the defective TLS may not be adequately compensated by HR [9].

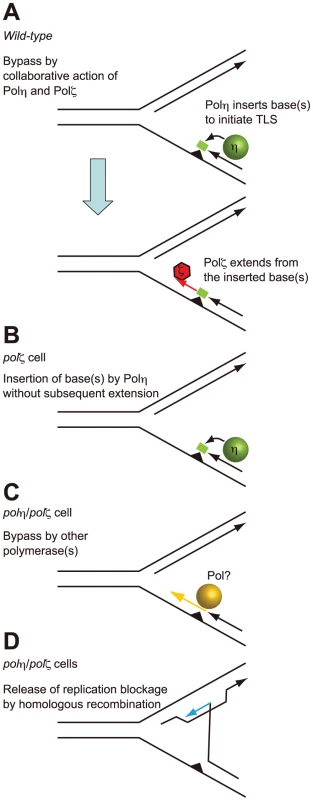

Fig. 7. Model for the sequential action of Polη and Polζ in wild-type, polζ, and polη/polζ clones.

(A) The two step-model for TLS. In wild-type cells, Polη is efficiently recruited to a replication blockage at a DNA lesion (green circle) on a template strand and inserts 1∼2 base(s) (green box) to bypass the lesion (filled triangle). Polζ further extends from these inserted base(s) (red arrow) before replicative DNA polymerases can take over from Polζ. (B) In polζ cells, after Polη inserts nucleotides opposite to DNA lesions, no other polymerases can effectively extend DNA synthesis for subsequent DNA synthesis by replicative polymerases. (C) In polη/polζ cells, other TLS polymerases carry out TLS. (D) The replication blockage may be released by a template switch to the intact sister chromatid using the HR machinery. SCE was induced more efficiently in the polη/polζ cells than in the polζ cells, which is consistent with the increased UV tolerance of polη/polζ cells, compared with polζ cells. Reconstitution of the polη/polζ cells with wild-type POLη, but not with the catalytically inactive POLη, significantly reduced the number of UV-induced SCE events. Thus, the degree of UV tolerance correlated with the number of UV-induced SCE events at least in polζ and polη/polζ cells. This observation suggests that, in addition to TLS, HR-mediated release from replication blockages contributes to a significantly higher UV tolerance in polη/polζ cells than in polζ cells.

Discussion

Polη is required for TLS across a much wider range of DNA lesions than indicated by the sensitivity of Polη-deficient cells. Analysis of XP-V cells indicates that Polη plays a major role in TLS past cyclobutane dimers and certain bulky adducts, but few other lesions. We demonstrate here that, in DT40 cells, Polη is also involved in the interaction of the replication machinery with different types of damage, such as those induced by chemical cross-linking agents (Figure 2), abasic sites (Figure 3 and Figure 4), and T-T(6-4) UV photoproduct (Figure 5). Thus, the deletion of polη in the polζ cells reversed their hypersensitivity to UV, MMS, cisplatin, and the ectopic expression of AID. Our finding that polη/polζ cells were significantly more tolerant to all tested DNA-damaging agents compared with polζ cells, reveals that neither of these polymerases is absolutely required for the tolerance of these types of damage during DNA replication. However, when Polη is present, Polζ is also required for efficient recovery from the effects of these damaging agents.

XP-V cells show a modest phenotype, including moderate sensitivity to UV and cisplatin [40], only in the presence of caffeine, and do not show significant sensitivity to MMS. Consequently, it was once believed that Polη does not play a role in TLS past DNA lesions induced by alkylating agents. However, in vitro biochemical studies have shown that purified Polη can bypass a variety of lesions including 7, 8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), O6-methylguanine, abasic sites, benzo pyrene adducts, and cisplatin intrastrand crosslinks [2], [41]–[43]. The present study helps demonstrate that Polη can indeed be involved in TLS past a wide variety of DNA lesions, even without caffeine treatment in DT40 cells. This idea is relevant to mammalian cells, since Polη focus formation is observed in mammalian cells following treatment with cisplatin and UV in the absence of caffeine [40].

The collaborative action of Polη and Polζ in TLS

The improved damage tolerance of polη/polζ cells, compared with polζ cells, suggests following several possibilities. One possibility is that Polζ somehow inhibits Polη action and that Polη does not actually have a significant role when Polζ is present. However this possibility may be unlikely, since physical interaction between Polη and Rev1, and Polη dependent recruitment of Rev1 to the DNA damage site support the sequential actions of Polη followed by Polζ rather than inhibitory action of Polζ on Polη [44]–[47]. Thus, more likely possibility is that, Polη generates a replicative intermediate in an attempt to bypass the lesion, but cannot complete an effective bypass reaction without Polζ (Figure 7A). We suggest that the abortive intermediates generated by Polη in the absence of Polζ lead to a difficult-to-rescue replication collapse, thereby accounting for the hypersensitivity of the single polζ mutant (Figure 7B). The modest phenotype of XP-V cells indicates that Polζ may efficiently mediate TLS past a variety of DNA lesions, either in collaboration with other polymerases or possibly on its own.

This situation can be explored further in the light of current TLS models. In the canonical model for TLS replication, arrest by agents such as UV, MMS, and cisplatin, leads to PCNA becoming mono-ubiquitinated [40], [48]–[50]. This increases the affinity of PCNA for Polη and other Y-family TLS polymerases by virtue of their UBM and UBZ ubiquitin-binding motif [44], [48], [50]–[52] and likely contributes to the accumulation of Y-family polymerases at the sites of blocked replication forks. It has been suggested that these polymerases can compete with each other by mass action to attempt to carry out TLS. In the case of CPDs, if Polη wins this competition; bypass can occur without the need for a second polymerase. However, with other lesions such as a T-T (6-4) photoproduct, there is currently no evidence to show that any single polymerase can complete bypass. Polη may be able to start the bypass by incorporating opposite at least the 5′ base of the lesion, but it cannot extend from the resulting mismatch (Figure 7A). This would explain the abortive intermediate referred to above. To complete TLS, Polζ is required to extend from the inserted nucleotides (Figure 7A), an explanation that is consistent with the sequential action of Polη and Polζ demonstrated in in vitro studies [2]. A further implication of this model is that no other polymerase can effectively substitute for Polζ in this extension step (Figure 7B).

The successive action of Polη and Polζ might be mediated by the association of the two polymerases with Rev1 [45], [53]. The idea of a Rev1-mediated switch from Polη to Polζ is supported by the fact that Polη tightly interacts with Rev1 [1], [46], [47], [53], [54]. Moreover, DNA-damage-induced Rev1 focus formation appears to be dependent on Polη [46], [47]. Adding to these findings, the present work establishes a role for Polη in the bypass of a wider range of DNA damage than previously thought and demonstrates the in vivo importance of the two-step bypass of many lesions.

The effect on TLS of depleting both Polη and Polζ is distinctly different in DT40 cells than in human cells. Ziv et al. showed that depletion of Rev3 sensitized cells to UV more severely at two days after irradiation in Polη-deficient XPV fibroblasts than in Polη-proficient control cells [22], although its impact on Polη-proficient DT40 cells was considerably stronger than on Polη-deficient DT40 cells. There are several explanations for this apparent difference. First, we favor the idea that DT40 may be a more reliable cell line than others to evaluate TLS by measuring cellular survival due to following reasons. The cell cycle distribution is distinctly different between DT40 and other mammalian cell lines. In DT40 cells, ∼70% of the cells are in the S phase, and the G1/S checkpoint does not function at all [55]. In most of the mammalian cell lines, on the other hand, more than 50% of the cells are in the G1 phase, and G1/S checkpoint works at least partially. Therefore, environmental DNA damage interferes with DNA replication more significantly in DT40 cells than in mammalian cell lines. Accordingly, TLS contributes to the cellular survival of the colony formation assay to a considerably higher extent in DT40 cells than in mammalian cell lines. Ziv et al., on the other hand, evaluated TLS by measuring the number of living cells at 48 hours after UV irradiation [22]. Since a majority of UV irradiated cells may have stayed outside the S phase at 48 hours, it is unclear whether this survival reflects the efficiency of TLS. The same laboratory also analyzed TLS past a cisplatin G-G intrastrand crosslink located in a gapped episomal plasmid [21]. Depletion of Rev3 with or without codepletion of Polη in U2OS cells resulted in an 80% reduction in TLS past the lesion, irrespective of the presence or absence of Polη. The relevance of this finding to TLS during the replication of chromosomal DNA remains elusive. Yoon et al. investigated TLS in a double-stranded plasmid containing a single 6-4 photoproduct as well as replication origins derived from the SV40 virus [23]. Depletion of Rev3 or Rev7 in NER-deficient XP-A fibroblasts reduced the efficiency of TLS in the episomal plasmid by approximately 50%, with a similar reduction obtained in XP-V fibroblasts. This result using human fibroblasts is clearly different from the data we obtained using DT40 cells. Given the close sequence similarity between the two polymerases in human and chicken cells, we consider it unlikely that the mechanisms of lesion bypass are fundamentally different between the two organisms. The apparent difference between mammalian cells and DT40 may be caused by the incomplete si-RNA mediated inhibition in human cells versus the null mutation we have used in DT40. Another possible reason to explain this difference is the active HR system in DT40 cells, and the different usage order of TLS DNA polymerases because the DT40 B lymphocyte line undergoes Ig V hypermutation through TLS [32]. The usefulness of the three episomal plasmid systems to the analysis of TLS occurring during replication of chromosomal DNAs should be further investigated [15], [21], [22], [28]. Irrespective of the reason for this apparent difference, our data clearly indicate that, as discussed above, under some conditions Polη can hinder the efficient progress of the replication fork past lesions mediated by Polζ.

Rescue of failed translesion synthesis by homologous recombination

It is remarkable that deletion of the three major TLS polymerase genes, POLη, POLκ, and POLζ, results in only a mild reduction in the growth kinetics of DT40 cells (Figure 6A). This is in marked contrast with the immediate cell death associated with the massive chromosomal breaks generated upon deletion of Rad51 [56]. These observations imply that during DNA replication, if replication blocks are encountered, HR can at least partially compensate for defective TLS. The significant functional redundancy between TLS and HR is supported by our previous report, which concludes that the deletion of both RAD18 and RAD54, a gene involved in HR, as well as the deletion of both REV3 and RAD54, are synthetically lethal to cells [9], [39]. We show here that depletion of Polη irrespective of the status of Polζ markedly increases the level of UV-induced SCE (Figure 6C), suggesting that DNA damage that cannot be resolved by TLS because of the absence of Polη may be resolved by HR, leading to increased SCE levels (Figure 7D). However, SCE is not induced to the same level in polζ cells (Figure 6C). Thus, nucleotide incorporation by Polη appears to represent a point of commitment in the TLS reaction beyond which rescue by HR is problematic. This is likely to be explained by the creation of an intermediate, possibly the mismatched primer terminus, which can be efficiently extended by Polζ, but which cannot readily initiate HR.

In summary, the significant increase in the cellular tolerance of polη/polζ cells to DNA-damaging agents, compared with polζ cells, can be partially attributable to more efficient HR in polη/polζ cells than in polζ cells. However, the normal level of TLS-dependent Ig V mutation and restoration of TLS during 6-4 photoproduct bypass in polη/polζ cells (Figure 4B) suggests that one or more other unidentified TLS polymerases can act as a substitute and carry out TLS when both Polη and Polζ are missing (Figure 7C).

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and cell culture

Generation of polζ (rev3) - and polη-deficient DT40 cells was described previously [9], [12]. To generate polη/polζ cells, we sequentially introduced two rev3 gene-disruption constructs (rev3-hygro and rev3-His) [9] into polη (PuroR/BlsR) cells. A puromycin-resistant XPA disruption construct was used to disrupt the single XPA allele and recreate the xpa/rev3 cell line. After removal of the BlsR marker gene from the polη/polζ cells by the transient expression of CRE recombinase, a blasticidin-resistant XPA disruption construct was used to generate the xpa/polζ/polη cell line. A puromycin-resistant POLκ disruption construct was used to generate polη/polζ/polκ cells. To make a POLη expression plasmid, we inserted human POLη cDNA into the multi-cloning sites (MCS) of an expression vector, pCR3-loxP-MCS-IRES-GFP-loxP [57]. A mutant Polη that lacks polymerase activity (Mutant POLη) was generated by inserting D115A/E116A mutations into human Polη cDNA. The conditions for cell culture, selection, and DNA transfection were described previously[58]. The growth properties of cells were analyzed as described previously [58].

AID overexpression by retrovirus infection

For the retrovirus infection, the pMSCV-IRES-GFP recombinant plasmid was constructed by ligating the 5.2 kb BamHI-NotI fragment from pMSCVhyg (Clontech) with the 1.2 kb BamHI-Not1 fragment from pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech). Mouse AID cDNA [33] was inserted between the BglII and EcoRI sites of pMSCV-IRES-GFP. The preparation and infection of the retrovirus were carried out as previously described [33]. Expression of the GFP was confirmed by flow cytometry. The efficiency of infection was more than 90% as assayed by GFP expression.

Assay of TLS past a T-T (6–4) photoproduct on episomal plasmid

pQTs and pQTo plasmids containing a T-T (6-4) photoproduct were generated and transfected into DT40 cells as previously described [28].

Chromosome aberration analysis

Karyotype analysis was performed as described previously [56]. Cells were treated with colcemid for 3 hours to enrich mitotic cells.

Measurement of SCE level

Measurement of SCE level was performed as described previously [38]. For UV-induced SCE, cells were suspended in PBS and irradiated with 0.25 J/m2 UV followed by BrdU labeling.

Ig Vλ mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted at 14 days after subcloning. The rearranged Vλ segments were PCR amplified using 5′-CAGGAGCTCGCGGGGCCGTCACTGATTGCCG-3′ as the forward primer in the leader-Vλ intron and 5′-GCGCAAGCTTCCCCAGCCTGCCGCCAAGTCCAAG-3′ as the reverse primer in the 3′ of the JCλ intron. To minimize PCR-introduced mutations, the high-fidelity polymerase, Phusion (Fynnzymes) was used for amplification (30 cycles at 94° C for 30 s; 60° C for 1 min; 72° C for 1 min). PCR products were cloned using a Zero Blunt TOPO PCR Cloning Kit (Invitrogen) and subjected to sequence analysis with the M13 forward (-20) or reverse primer. Sequence alignment using GENETYX-MAC (Software Development, Tokyo) allowed the identification of changes from the parental sequences in each clone.

As described previously [59], all sequence changes were assigned to one of three categories: point mutation, gene conversion, or ambiguous. This discrimination is based on the published sequences of Vλ pseudogenes that can act as donors for gene conversion. For each mutation, the database of Vλ pseudogenes was searched for a potential donor. If no pseudogene donor containing a string >9 bp could be found, the mutation was categorized as a non-templated point mutation. If such a string was identified and there were further mutations that could be explained by the same donor, then all these mutations were categorized as a single long-tract gene conversion event. If there were no further mutations, indicating that the isolated mutation could have arisen through a conversion mechanism or could have been non-templated, it was categorized as ambiguous.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. FriedbergEC

LehmannAR

FuchsRP

2005

Trading places: how do DNA polymerases switch during translesion DNA synthesis?

Mol Cell

18

499

505

2. PrakashS

JohnsonRE

PrakashL

2005

Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function.

Annu Rev Biochem

74

317

353

3. JohnsonRE

KondratickCM

PrakashS

PrakashL

1999

hRAD30 mutations in the variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum.

Science

285

263

265

4. MasutaniC

KusumotoR

YamadaA

DohmaeN

YokoiM

1999

The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase eta.

Nature

399

700

704

5. LehmannAR

2002

Replication of damaged DNA in mammalian cells: new solutions to an old problem.

Mutat Res

509

23

34

6. Van SlounPP

VarletI

SonneveldE

BoeiJJ

RomeijnRJ

2002

Involvement of mouse Rev3 in tolerance of endogenous and exogenous DNA damage.

Mol Cell Biol

22

2159

2169

7. MizutaniA

OkadaT

ShibutaniS

SonodaE

HocheggerH

2004

Extensive chromosomal breaks are induced by tamoxifen and estrogen in DNA repair-deficient cells.

Cancer Res

64

3144

3147

8. NojimaK

HocheggerH

SaberiA

FukushimaT

KikuchiK

2005

Multiple repair pathways mediate tolerance to chemotherapeutic cross-linking agents in vertebrate cells.

Cancer Res

65

11704

11711

9. SonodaE

OkadaT

ZhaoGY

TateishiS

ArakiK

2003

Multiple roles of Rev3, the catalytic subunit of polzeta in maintaining genome stability in vertebrates.

EMBO J

22

3188

3197

10. WuX

TakenakaK

SonodaE

HocheggerH

KawanishiS

2006

Critical roles for polymerase zeta in cellular tolerance to nitric oxide-induced DNA damage.

Cancer Res

66

748

754

11. LehmannAR

2006

New functions for Y family polymerases.

Mol Cell

24

493

495

12. KawamotoT

ArakiK

SonodaE

YamashitaYM

HaradaK

2005

Dual roles for DNA polymerase eta in homologous DNA recombination and translesion DNA synthesis.

Mol Cell

20

793

799

13. JohnsonRE

WashingtonMT

PrakashS

PrakashL

2000

Fidelity of human DNA polymerase eta.

J Biol Chem

275

7447

7450

14. McCullochSD

KokoskaRJ

MasutaniC

IwaiS

HanaokaF

2004

Preferential cis-syn thymine dimer bypass by DNA polymerase eta occurs with biased fidelity.

Nature

428

97

100

15. YoonJH

PrakashL

PrakashS

2009

Highly error-free role of DNA polymerase eta in the replicative bypass of UV-induced pyrimidine dimers in mouse and human cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

106

18219

18224

16. JohnsonRE

WashingtonMT

HaracskaL

PrakashS

PrakashL

2000

Eukaryotic polymerases iota and zeta act sequentially to bypass DNA lesions.

Nature

406

1015

1019

17. WoodgateR

2001

Evolution of the two-step model for UV-mutagenesis.

Mutat Res

485

83

92

18. WolfleWT

JohnsonRE

MinkoIG

LloydRS

PrakashS

2006

Replication past a trans-4-hydroxynonenal minor-groove adduct by the sequential action of human DNA polymerases iota and kappa.

Mol Cell Biol

26

381

386

19. LawrenceCW

2007

Following the RAD6 pathway.

DNA Repair (Amst)

6

676

686

20. OkadaT

SonodaE

YoshimuraM

KawanoY

SayaH

2005

Multiple roles of vertebrate REV genes in DNA repair and recombination.

Mol Cell Biol

25

6103

6111

21. ShacharS

ZivO

AvkinS

AdarS

WittschiebenJ

2009

Two-polymerase mechanisms dictate error-free and error-prone translesion DNA synthesis in mammals.

EMBO J

28

383

393

22. ZivO

GeacintovN

NakajimaS

YasuiA

LivnehZ

2009

DNA polymerase zeta cooperates with polymerases kappa and iota in translesion DNA synthesis across pyrimidine photodimers in cells from XPV patients.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

106

11552

11557

23. YoonJH

PrakashL

PrakashS

2010

Error-free replicative bypass of (6-4) photoproducts by DNA polymerase zeta in mouse and human cells.

Genes Dev

24

123

128

24. SaleJE

2004

Immunoglobulin diversification in DT40: a model for vertebrate DNA damage tolerance.

DNA Repair (Amst)

3

693

702

25. ArakawaH

HauschildJ

BuersteddeJM

2002

Requirement of the activation-induced deaminase (AID) gene for immunoglobulin gene conversion.

Science

295

1301

1306

26. HarrisRS

SaleJE

Petersen-MahrtSK

NeubergerMS

2002

AID is essential for immunoglobulin V gene conversion in a cultured B cell line.

Curr Biol

12

435

438

27. Di NoiaJM

NeubergerMS

2007

Molecular mechanisms of antibody somatic hypermutation.

Annu Rev Biochem

76

1

22

28. SzutsD

MarcusAP

HimotoM

IwaiS

SaleJE

2008

REV1 restrains DNA polymerase zeta to ensure frame fidelity during translesion synthesis of UV photoproducts in vivo.

Nucleic Acids Res

36

6767

6780

29. WangYC

MaherVM

MitchellDL

McCormickJJ

1993

Evidence from mutation spectra that the UV hypermutability of xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells reflects abnormal, error-prone replication on a template containing photoproducts.

Mol Cell Biol

13

4276

4283

30. WatersHL

SeetharamS

SeidmanMM

KraemerKH

1993

Ultraviolet hypermutability of a shuttle vector propagated in xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells.

J Invest Dermatol

101

744

748

31. BebenekK

MatsudaT

MasutaniC

HanaokaF

KunkelTA

2001

Proofreading of DNA polymerase eta-dependent replication errors.

J Biol Chem

276

2317

2320

32. SaberiA

NakaharaM

SaleJE

KikuchiK

ArakawaH

2008

The 9-1-1 DNA clamp is required for immunoglobulin gene conversion.

Mol Cell Biol

28

6113

6122

33. ShinkuraR

ItoS

BegumNA

NagaokaH

MuramatsuM

2004

Separate domains of AID are required for somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination.

Nat Immunol

5

707

712

34. ArakawaH

MoldovanGL

SaribasakH

SaribasakNN

JentschS

2006

A role for PCNA ubiquitination in immunoglobulin hypermutation.

PLoS Biol

4

e366

doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040366

35. FriedbergEC

WalkerGC

SiedeW

WoodRD

SchultzRA

2006

DNA repair and mutagenesis.

36. TakenakaK

OgiT

OkadaT

SonodaE

GuoC

2006

Involvement of vertebrate Polkappa in translesion DNA synthesis across DNA monoalkylation damage.

J Biol Chem

281

2000

2004

37. HocheggerH

SonodaE

TakedaS

2004

Post-replication repair in DT40 cells: translesion polymerases versus recombinases.

Bioessays

26

151

158

38. SonodaE

SasakiMS

MorrisonC

Yamaguchi-IwaiY

TakataM

1999

Sister chromatid exchanges are mediated by homologous recombination in vertebrate cells.

Mol Cell Biol

19

5166

5169

39. YamashitaYM

OkadaT

MatsusakaT

SonodaE

ZhaoGY

2002

RAD18 and RAD54 cooperatively contribute to maintenance of genomic stability in vertebrate cells.

EMBO J

21

5558

5566

40. AlbertellaMR

GreenCM

LehmannAR

O'ConnorMJ

2005

A role for polymerase eta in the cellular tolerance to cisplatin-induced damage.

Cancer Res

65

9799

9806

41. KusumotoR

MasutaniC

IwaiS

HanaokaF

2002

Translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase eta across thymine glycol lesions.

Biochemistry

41

6090

6099

42. MasutaniC

KusumotoR

IwaiS

HanaokaF

2000

Mechanisms of accurate translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase eta.

EMBO J

19

3100

3109

43. WashingtonMT

WolfleWT

SprattTE

PrakashL

PrakashS

2003

Yeast DNA polymerase eta makes functional contacts with the DNA minor groove only at the incoming nucleoside triphosphate.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

100

5113

5118

44. GuoC

TangTS

BienkoM

ParkerJL

BielenAB

2006

Ubiquitin-binding motifs in REV1 protein are required for its role in the tolerance of DNA damage.

Mol Cell Biol

26

8892

8900

45. MurakumoY

OguraY

IshiiH

NumataS

IchiharaM

2001

Interactions in the error-prone postreplication repair proteins hREV1, hREV3, and hREV7.

J Biol Chem

276

35644

35651

46. AkagiJ

MasutaniC

KataokaY

KanT

OhashiE

2009

Interaction with DNA polymerase eta is required for nuclear accumulation of REV1 and suppression of spontaneous mutations in human cells.

DNA Repair (Amst)

8

585

599

47. TissierA

KannoucheP

ReckMP

LehmannAR

FuchsRP

2004

Co-localization in replication foci and interaction of human Y-family members, DNA polymerase pol eta and REVl protein.

DNA Repair (Amst)

3

1503

1514

48. KannouchePL

WingJ

LehmannAR

2004

Interaction of human DNA polymerase eta with monoubiquitinated PCNA: a possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage.

Mol Cell

14

491

500

49. NiimiA

BrownS

SabbionedaS

KannouchePL

ScottA

2008

Regulation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen ubiquitination in mammalian cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

105

16125

16130

50. WatanabeK

TateishiS

KawasujiM

TsurimotoT

InoueH

2004

Rad18 guides poleta to replication stalling sites through physical interaction and PCNA monoubiquitination.

EMBO J

23

3886

3896

51. BienkoM

GreenCM

CrosettoN

RudolfF

ZapartG

2005

Ubiquitin-binding domains in Y-family polymerases regulate translesion synthesis.

Science

310

1821

1824

52. PloskyBS

VidalAE

Fernandez de HenestrosaAR

McLeniganMP

McDonaldJP

2006

Controlling the subcellular localization of DNA polymerases iota and eta via interactions with ubiquitin.

EMBO J

25

2847

2855

53. GuoC

FischhaberPL

Luk-PaszycMJ

MasudaY

ZhouJ

2003

Mouse Rev1 protein interacts with multiple DNA polymerases involved in translesion DNA synthesis.

EMBO J

22

6621

6630

54. YuasaMS

MasutaniC

HiranoA

CohnMA

YamaizumiM

2006

A human DNA polymerase eta complex containing Rad18, Rad6 and Rev1; proteomic analysis and targeting of the complex to the chromatin-bound fraction of cells undergoing replication fork arrest.

Genes Cells

11

731

744

55. YamazoeM

SonodaE

HocheggerH

TakedaS

2004

Reverse genetic studies of the DNA damage response in the chicken B lymphocyte line DT40.

DNA Repair (Amst)

3

1175

1185

56. SonodaE

SasakiMS

BuersteddeJM

BezzubovaO

ShinoharaA

1998

Rad51-deficient vertebrate cells accumulate chromosomal breaks prior to cell death.

EMBO J

17

598

608

57. FujimoriA

TachiiriS

SonodaE

ThompsonLH

DharPK

2001

Rad52 partially substitutes for the Rad51 paralog XRCC3 in maintaining chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells.

EMBO J

20

5513

5520

58. TakataM

SasakiMS

SonodaE

MorrisonC

HashimotoM

1998

Homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways of DNA double-strand break repair have overlapping roles in the maintenance of chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells.

EMBO J

17

5497

5508

59. SaleJE

CalandriniDM

TakataM

TakedaS

NeubergerMS

2001

Ablation of XRCC2/3 transforms immunoglobulin V gene conversion into somatic hypermutation.

Nature

412

921

926

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 10

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Common Genetic Variants and Modification of Penetrance of -Associated Breast Cancer

- FSHD: A Repeat Contraction Disease Finally Ready to Expand (Our Understanding of Its Pathogenesis)

- Genome-Wide Identification of Targets and Function of Individual MicroRNAs in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Allele-Specific Down-Regulation of Expression Induced by Retinoids Contributes to Climate Adaptations

- The Meiotic Recombination Checkpoint Suppresses NHK-1 Kinase to Prevent Reorganisation of the Oocyte Nucleus in

- Actin Depolymerizing Factors Cofilin1 and Destrin Are Required for Ureteric Bud Branching Morphogenesis

- DSIF and RNA Polymerase II CTD Phosphorylation Coordinate the Recruitment of Rpd3S to Actively Transcribed Genes

- Continuous Requirement for the Clr4 Complex But Not RNAi for Centromeric Heterochromatin Assembly in Fission Yeast Harboring a Disrupted RITS Complex

- Genome-Wide Association Study of Blood Pressure Extremes Identifies Variant near Associated with Hypertension

- The Cytosine Methyltransferase DRM2 Requires Intact UBA Domains and a Catalytically Mutated Paralog DRM3 during RNA–Directed DNA Methylation in

- β-Actin and γ-Actin Are Each Dispensable for Auditory Hair Cell Development But Required for Stereocilia Maintenance

- Genetic Association Study Identifies as a Risk Gene for Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy

- Evidence for a Xer/ System for Chromosome Resolution in Archaea

- Four Novel Loci (19q13, 6q24, 12q24, and 5q14) Influence the Microcirculation

- Lifespan Extension by Preserving Proliferative Homeostasis in

- Ancient and Recent Adaptive Evolution of Primate Non-Homologous End Joining Genes

- Loss of the p53/p63 Regulated Desmosomal Protein Perp Promotes Tumorigenesis

- Altering a Histone H3K4 Methylation Pathway in Glomerular Podocytes Promotes a Chronic Disease Phenotype

- Characterization of LINE-1 Ribonucleoprotein Particles

- Conserved Genes Act as Modifiers of Invertebrate SMN Loss of Function Defects

- Alternative Splicing at a NAGNAG Acceptor Site as a Novel Phenotype Modifier

- Tight Regulation of the Gene of the KplE1 Prophage: A New Paradigm for Integrase Gene Regulation

- Conjugative DNA Transfer Induces the Bacterial SOS Response and Promotes Antibiotic Resistance Development through Integron Activation

- Nasty Viruses, Costly Plasmids, Population Dynamics, and the Conditions for Establishing and Maintaining CRISPR-Mediated Adaptive Immunity in Bacteria

- Stress-Induced Activation of Heterochromatic Transcription

- H3K27me3 Profiling of the Endosperm Implies Exclusion of Polycomb Group Protein Targeting by DNA Methylation

- Simultaneous Disruption of Two DNA Polymerases, Polη and Polζ, in Avian DT40 Cells Unmasks the Role of Polη in Cellular Response to Various DNA Lesions

- Characterising and Predicting Haploinsufficiency in the Human Genome

- Dual Functions of ASCIZ in the DNA Base Damage Response and Pulmonary Organogenesis

- Pervasive Cryptic Epistasis in Molecular Evolution

- Transition from Positive to Neutral in Mutation Fixation along with Continuing Rising Fitness in Thermal Adaptive Evolution

- Comprehensive Analysis Reveals Dynamic and Evolutionary Plasticity of Rab GTPases and Membrane Traffic in

- Regulates Tissue-Specific Mitochondrial DNA Segregation

- Role for the Mammalian Swi5-Sfr1 Complex in DNA Strand Break Repair through Homologous Recombination

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Identification of Targets and Function of Individual MicroRNAs in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Common Genetic Variants and Modification of Penetrance of -Associated Breast Cancer

- Allele-Specific Down-Regulation of Expression Induced by Retinoids Contributes to Climate Adaptations

- Simultaneous Disruption of Two DNA Polymerases, Polη and Polζ, in Avian DT40 Cells Unmasks the Role of Polη in Cellular Response to Various DNA Lesions

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání