-

Články

Reklama

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

ReklamaMutagenesis by AID: Being in the Right Place at the Right Time

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005489

Category: Perspective

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005489Summary

article has not abstract

Deamination of cytosine is a common consequence of the natural hydrolytic decay of DNA. However, it is also part of a mutagenesis programme in immune cells, initiated by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) acting on the genes that encode antibodies. Cytosine deamination by AID results in a staggering number of localised point mutations. This is achieved within a few cell divisions despite the rather innocuous nature of base change in the DNA, deoxy-uracil, which is efficiently removed by the uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG). Highly abundant during S phase, the main role of UNG is to remove uracil misincorporated during DNA replication, but it can act at other times, both on double and single stranded DNA (dsDNA and ssDNA, respectively). Cells have a back up glycosylase, SMUG1 [1], that removes uracil from double stranded DNA, a pathway ideally suited to faithfully repair deaminated cytosines outside replication. It has been quite a mystery why repair of uracils induced by AID is mostly mutagenic; a favoured hypothesis was that uracil excision at the wrong time during the cell cycle would prevent faithful repair. The work by Le and Maizels [2] on this issue goes some way to resolving this question.

AID is a powerful mutator of single stranded DNA in B cells. Its activity can be misdirected to other parts of the genome, leading to translocations and oncogenic transformation in many B cell malignancies. It is also responsible for clustered kataegic mutations, the telltale of indiscriminate deaminase activity on ssDNA [3] found in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemias and other cancers [4,5]. It is therefore not surprising that under normal circumstances AID entry into the cell nucleus is tightly regulated and, once there, its abundance is limited. The key mechanism regulating AID abundance is through nuclear degradation and, in order to balance this, AID is rapidly exported to the cytoplasm where it resides as part of a stable complex [6]. Indeed, loss of AID’s C-terminal nuclear export signal, a mutation observed in immunodeficiency patients, leads to rapid degradation of the protein as it cannot be translocated back to the cytosol.

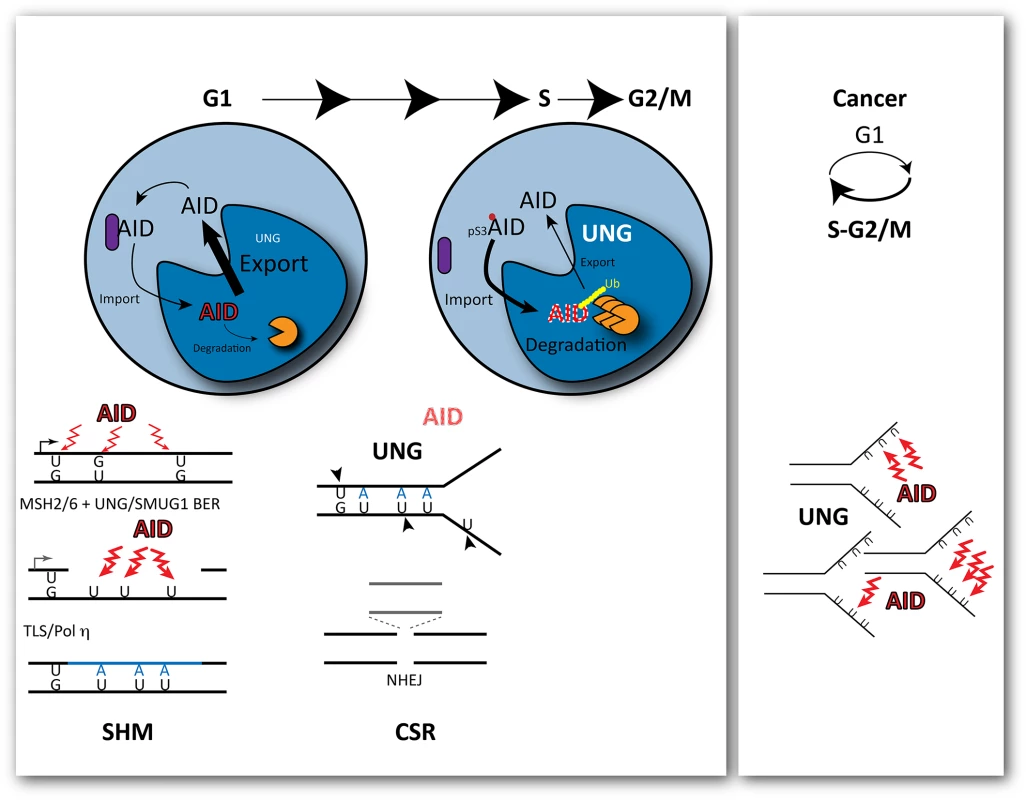

Thus, the mutagenic activity of AID depends on its ability to overcome faithful uracil repair but also to remain in the nucleus of B cells. In an elegant study, Le and Maizels [2] have illuminated important aspects of how this is accomplished by manipulating the subcellular localisation of AID at different times of the cell cycle. By fusing AID to cell-cycle regulated "degrons," they limited the levels of AID to mainly G1 or S-G2/M and show that deamination by AID is only mutagenic during G1 (Fig 1). This had been intimated by the Reynaud group in 2002 [7] based on mutation emergence post-AID induction and, more recently, by the Jolly group, by inhibiting UNG in G1 or S-G2/M [8] using a strategy similar to Le and Maizels [2]. However, neither study separated AID activity from processing of the deaminated C or explained how AID activity was restricted to G1. The new study by Le and Maizels fully explains these results by demonstrating that the enforced presence of AID in the nucleus is toxic in S phase (with the cellular response leading to its rapid degradation), whereas it is tolerated during G1, when it enhances hypermutation and class switching [2]. The study goes further in providing some mechanistic insight as to how phosphorylation of AID modulates its cell cycle related stability.

Fig. 1. Outcomes of cytosine deamination during the cell cycle.

AID is selectively recruited to the immunoglobulin locus by transcription during G1. Its mutagenic activity is restricted to G1 during the cell cycle, with rapid nuclear degradation during S phase. This is modulated by phosphorylation of AID at Ser3, which promotes its rapid degradation in the cell nucleus. As a consequence, cytosine deamination-resulting uracils opposite guanines are processed before replication by base excision repair and non-canonical mismatch repair, creating single stranded gaps in the DNA and further localised substrates for deamination. At the transition to S phase, the levels of UNG, the uracil glycosylase that removes uracils, are increased leading to double-strand breaks and deletions that promote class switching though the non-homologous end joining of the broken ends. In cancer cells, cell-cycle deregulation can expose single stranded DNA during replication to the activity of AID, leading to clustered mutations. Mutagenesis induced by AID results from a plethora of misfortunes, from simple miscoding by uracil/abasic sites to mismatch-induced error-prone repair or the generation of double strand breaks (DSBs) resolved with loss of genetic information by the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway. All these events can result from engaging DNA repair at the wrong time, during G1 (Fig 1). Recruitment of the Mismatch Repair (MMR) factor MSH2 to U:G mismatches in dsDNA prior to replication in the presence of nearby uracils that are substrates of Base Excision Repair (BER), which leads to ssDNA gaps [9] (a further substrate of deamination and uracil excision) and, eventually, translesion DNA synthesis by Polη. Increased UNG levels in early S phase facilitate uracil excision in ss and dsDNA, leading to breaks before the homologous recombination pathway has a chance to act and to NHEJ-mediated deletions.

With AID activity restricted to G1, it follows that secondary deaminations on the ssDNA generated during MMR of the initial U:G mispairs could be perpetuated by Polη during gap filling as U:A pairs. These uracils would no longer be the substrate of MMR or a preferred substrate for SMUG1 (preventing futile rounds of additional MMR or BER), but would offer additional substrates for UNG. This scenario also obviates a requirement for persistent abasic sites, which are intrinsically chemically unstable, for the generation of transversions at G:C pairs or of breaks. Indeed, the strict association of cell division with DSBs required for class switching could just reflect a requirement for high levels of UNG activity on closely spaced U:G and U:A pairs.

Le and Maizels go on to show that the abundance of AID is modulated by phosphorylation at Ser3, resulting in enhanced degradation in G1 [2]. This suggests that the balance between nuclear import and export of AID is cell-cycle regulated. AID is preferentially recruited to the immunoglobulin locus by transcription, which takes place mostly during G1. Thus, its activity leads to localized mutagenesis when its presence in the cell nucleus can be tolerated. During S phase, when ssDNA is abundant, AID's presence in the nucleus would lead to catastrophic global mutagenesis; therefore, it is actively degraded, exported, and kept away in a cytosolic complex [10]. Questions remain regarding how phosphorylation itself is regulated, and how exactly it modulates AID abundance: does it increase active import, does it reduce export, or does it release cytosolic retention? Alternatively, phosphorylation could affect the ubiquitin dependent and/or independent degradation of nuclear AID.

In the meantime, Le and Maizels findings also offer an immediate practical application, expanding the potential use of modified or enhanced AID enzymes as a biotechnology tool to evolve antibodies in vitro by manipulating the toxicity of AID in cells and targeting its activity to the time-window during which it can best do its job [2].

Zdroje

1. Dingler FA, Kemmerich K, Neuberger MS, Rada C. Uracil excision by endogenous SMUG1 glycosylase promotes efficient Ig class switching and impacts on A:T substitutions during somatic mutation. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44 : 1925–1935. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444482 24771041

2. Le Q, Maizels N. Cell Cycle Regulates Nuclear Stability of AID and Determines the Cellular Response to AID. PLoS Genet.

3. Taylor BJ, Nik-Zainal S, Wu YL, Stebbings LA, Raine K, Campbell PJ, et al. DNA deaminases induce break-associated mutation showers with implication of APOBEC3B and 3A in breast cancer kataegis. Elife. 2013 Apr 16;2:e00534. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00534 23599896

4. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SAJR, Behjati S, Biankin AV, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500 : 415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477 23945592

5. Pettersen HS, Galashevskaya A, Doseth B, Sousa MML, Sarno A, Visnes T, et al. AID expression in B-cell lymphomas causes accumulation of genomic uracil and a distinct AID mutational signature. DNA Repair (Amst). 2015;25 : 60–71.

6. Orthwein A, Di Noia JM. Activation induced deaminase: how much and where? Seminars in Immunology. 2012;24 : 246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.05.001 22687198

7. Faili A, Aoufouchi S, Guéranger Q, Zober C, Léon A, Bertocci B, et al. AID-dependent somatic hypermutation occurs as a DNA single-strand event in the BL2 cell line. Nat Immunol. 2002;3 : 815–821. 12145648

8. Sharbeen G, Yee CWY, Smith AL, Jolly CJ. Ectopic restriction of DNA repair reveals that UNG2 excises AID-induced uracils predominantly or exclusively during G1 phase. J Exp Med. 2012;209 : 965–974. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112379 22529268

9. Peña-Diaz J, Jiricny J. Mammalian mismatch repair: error-free or error-prone? Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37 : 206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.03.001 22475811

10. Häsler J, Rada C, Neuberger MS. The cytoplasmic AID complex. Seminars in Immunology. 2012;24 : 273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.05.004 22698843

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The Chromatin Protein DUET/MMD1 Controls Expression of the Meiotic Gene during Male Meiosis inČlánek Tissue-Specific Gain of RTK Signalling Uncovers Selective Cell Vulnerability during Embryogenesis

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 9

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Retraction: RNAi-Dependent and Independent Control of LINE1 Accumulation and Mobility in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Signaling from Within: Endocytic Trafficking of the Robo Receptor Is Required for Midline Axon Repulsion

- A Splice Region Variant in Lowers Non-high Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Protects against Coronary Artery Disease

- The Chromatin Protein DUET/MMD1 Controls Expression of the Meiotic Gene during Male Meiosis in

- A NIMA-Related Kinase Suppresses the Flagellar Instability Associated with the Loss of Multiple Axonemal Structures

- Slit-Dependent Endocytic Trafficking of the Robo Receptor Is Required for Son of Sevenless Recruitment and Midline Axon Repulsion

- Expression of Concern: Protein Under-Wrapping Causes Dosage Sensitivity and Decreases Gene Duplicability

- Mutagenesis by AID: Being in the Right Place at the Right Time

- Identification of as a Genetic Modifier That Regulates the Global Orientation of Mammalian Hair Follicles

- Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

- Evaluating the Performance of Fine-Mapping Strategies at Common Variant GWAS Loci

- KLK5 Inactivation Reverses Cutaneous Hallmarks of Netherton Syndrome

- Differential Expression of Ecdysone Receptor Leads to Variation in Phenotypic Plasticity across Serial Homologs

- Receptor Polymorphism and Genomic Structure Interact to Shape Bitter Taste Perception

- Cognitive Function Related to the Gene Acquired from an LTR Retrotransposon in Eutherians

- Critical Function of γH2A in S-Phase

- Arabidopsis AtPLC2 Is a Primary Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Phosphoinositide Metabolism and the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response

- XBP1-Independent UPR Pathways Suppress C/EBP-β Mediated Chondrocyte Differentiation in ER-Stress Related Skeletal Disease

- Integration of Genome-Wide SNP Data and Gene-Expression Profiles Reveals Six Novel Loci and Regulatory Mechanisms for Amino Acids and Acylcarnitines in Whole Blood

- A Genome-Wide Association Study of a Biomarker of Nicotine Metabolism

- Cell Cycle Regulates Nuclear Stability of AID and Determines the Cellular Response to AID

- A Genome-Wide Association Analysis Reveals Epistatic Cancellation of Additive Genetic Variance for Root Length in

- Tissue-Specific Gain of RTK Signalling Uncovers Selective Cell Vulnerability during Embryogenesis

- RAB-10-Dependent Membrane Transport Is Required for Dendrite Arborization

- Basolateral Endocytic Recycling Requires RAB-10 and AMPH-1 Mediated Recruitment of RAB-5 GAP TBC-2 to Endosomes

- Dynamic Contacts of U2, RES, Cwc25, Prp8 and Prp45 Proteins with the Pre-mRNA Branch-Site and 3' Splice Site during Catalytic Activation and Step 1 Catalysis in Yeast Spliceosomes

- ARID1A Is Essential for Endometrial Function during Early Pregnancy

- Predicting Carriers of Ongoing Selective Sweeps without Knowledge of the Favored Allele

- An Interaction between RRP6 and SU(VAR)3-9 Targets RRP6 to Heterochromatin and Contributes to Heterochromatin Maintenance in

- Photoreceptor Specificity in the Light-Induced and COP1-Mediated Rapid Degradation of the Repressor of Photomorphogenesis SPA2 in Arabidopsis

- Autophosphorylation of the Bacterial Tyrosine-Kinase CpsD Connects Capsule Synthesis with the Cell Cycle in

- Multimer Formation Explains Allelic Suppression of PRDM9 Recombination Hotspots

- Rescheduling Behavioral Subunits of a Fixed Action Pattern by Genetic Manipulation of Peptidergic Signaling

- A Gene Regulatory Program for Meiotic Prophase in the Fetal Ovary

- Cell-Autonomous Gβ Signaling Defines Neuron-Specific Steady State Serotonin Synthesis in

- Discovering Genetic Interactions in Large-Scale Association Studies by Stage-wise Likelihood Ratio Tests

- The RCC1 Family Protein TCF1 Regulates Freezing Tolerance and Cold Acclimation through Modulating Lignin Biosynthesis

- The AMPK, Snf1, Negatively Regulates the Hog1 MAPK Pathway in ER Stress Response

- The Parkinson’s Disease-Associated Protein Kinase LRRK2 Modulates Notch Signaling through the Endosomal Pathway

- Multicopy Single-Stranded DNA Directs Intestinal Colonization of Enteric Pathogens

- Recurrent Domestication by Lepidoptera of Genes from Their Parasites Mediated by Bracoviruses

- Three Different Pathways Prevent Chromosome Segregation in the Presence of DNA Damage or Replication Stress in Budding Yeast

- Identification of Four Mouse Diabetes Candidate Genes Altering β-Cell Proliferation

- The Intolerance of Regulatory Sequence to Genetic Variation Predicts Gene Dosage Sensitivity

- Synergistic and Dose-Controlled Regulation of Cellulase Gene Expression in

- Genome Sequence and Transcriptome Analyses of : Metabolic Tools for Enhanced Algal Fitness in the Prominent Order Prymnesiales (Haptophyceae)

- Ty3 Retrotransposon Hijacks Mating Yeast RNA Processing Bodies to Infect New Genomes

- FUS Interacts with HSP60 to Promote Mitochondrial Damage

- Point Mutations in Centromeric Histone Induce Post-zygotic Incompatibility and Uniparental Inheritance

- Genome-Wide Association Study with Targeted and Non-targeted NMR Metabolomics Identifies 15 Novel Loci of Urinary Human Metabolic Individuality

- Outer Hair Cell Lateral Wall Structure Constrains the Mobility of Plasma Membrane Proteins

- A Large-Scale Functional Analysis of Putative Target Genes of Mating-Type Loci Provides Insight into the Regulation of Sexual Development of the Cereal Pathogen

- A Genetic Selection for Mutants Reveals an Interaction between DNA Polymerase IV and the Replicative Polymerase That Is Required for Translesion Synthesis

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Arabidopsis AtPLC2 Is a Primary Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Phosphoinositide Metabolism and the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response

- Bridges Meristem and Organ Primordia Boundaries through , , and during Flower Development in

- KLK5 Inactivation Reverses Cutaneous Hallmarks of Netherton Syndrome

- XBP1-Independent UPR Pathways Suppress C/EBP-β Mediated Chondrocyte Differentiation in ER-Stress Related Skeletal Disease

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání