-

Články

Reklama

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Reklamaand Regulate Reproductive Habit in Rice

Sexual reproduction is essential for the life cycle of most angiosperms. However, pseudovivipary is an important reproductive strategy in some grasses. In this mode of reproduction, asexual propagules are produced in place of sexual reproductive structures. However, the molecular mechanism of pseudovivipary still remains a mystery. In this work, we found three naturally occurring mutants in rice, namely, phoenix (pho), degenerative palea (dep), and abnormal floral organs (afo). Genetic analysis of them indicated that the stable pseudovivipary mutant pho was a double mutant containing both a Mendelian mutation in DEP and a non-Mendelian mutation in AFO. Further map-based cloning and microarray analysis revealed that dep mutant was caused by a genetic alteration in OsMADS15 while afo was caused by an epigenetic mutation in OsMADS1. Thus, OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 are both required to ensure sexual reproduction in rice and mutations of them lead to the switch of reproductive habit from sexual to asexual in rice. For the first time, our results reveal two regulators for sexual and asexual reproduction modes in flowering plants. In addition, our findings also make it possible to manipulate the reproductive strategy of plants, at least in rice.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000818

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000818Summary

Sexual reproduction is essential for the life cycle of most angiosperms. However, pseudovivipary is an important reproductive strategy in some grasses. In this mode of reproduction, asexual propagules are produced in place of sexual reproductive structures. However, the molecular mechanism of pseudovivipary still remains a mystery. In this work, we found three naturally occurring mutants in rice, namely, phoenix (pho), degenerative palea (dep), and abnormal floral organs (afo). Genetic analysis of them indicated that the stable pseudovivipary mutant pho was a double mutant containing both a Mendelian mutation in DEP and a non-Mendelian mutation in AFO. Further map-based cloning and microarray analysis revealed that dep mutant was caused by a genetic alteration in OsMADS15 while afo was caused by an epigenetic mutation in OsMADS1. Thus, OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 are both required to ensure sexual reproduction in rice and mutations of them lead to the switch of reproductive habit from sexual to asexual in rice. For the first time, our results reveal two regulators for sexual and asexual reproduction modes in flowering plants. In addition, our findings also make it possible to manipulate the reproductive strategy of plants, at least in rice.

Introduction

Flowering is an important process essential for sexual reproduction, seed development and fruit production. Although flowering is composed of a series of typically irreversible sequential events, reversion from floral to vegetative growth is frequently observed in nature. Reversions can be divided into two categories: inflorescence reversion, in which vegetative growth is resumed after or intercalated within inflorescence development, and flower reversion, in which vegetative growth is resumed in an individual flower [1],[2]. Reversion, which can serve a function in the life history strategy (perenniality) or reproductive habit (pseudovivipary), is essential for the life cycle of some plant species [1],[2].

Vivipary in flowering plants is defined as the precocious and continuous growth of the offspring while still attached to the parent plant [3],[4]. Vivipary can be divided into two distinct types: true vivipary and pseudovivipary [3]. True vivipary is a sexual reproduction process in which seeds germinate before they detach from maternal plant. On the other hand, pseudovivipary is a specific asexual reproductive strategy in which bulbils or plantlets replace sexual reproductive structures [3],[5]. Pseudovivipary has been widely recorded in monocots, in particular grasses that grow in extreme environments [1], [3], [5]–[11]. Characteristics of the environments which favour pseudovivipary include climate changes, high precipitation and humidity, drought, fungal infection, high altitudes and latitudes, late-thawing habitats, or arid/semi-arid areas [1],[3],[5]. Several authors have argued that pseudovivipary has evolved in response to a short growing season, enabling plants to rapidly complete the cycle of offspring production, germination and establishment during the brief periods favourable to growth and reproduction [3]. In developmental terms pseudovivipary occurs in two principal ways. The first way to proliferate, as in Festuca ovina, Poa alpina and Poa bulbosa, is through the transformation of the spikelet axis into the leafy shoot. The second way is to form the first leaf of the plantlet by lemma elongation, as is the case in Deschampsia caespitose and Poa robusta [1],[11]. In some cases, such as Deschampsia alpine and Phleum pratense, both modes of propagule development have been found in a single plant [11], indicating that the molecular difference between the two types of pseudovivipary might be rather small.

Pseudovivipary has fascinated biologists, as elucidation of its mechanism could lead to an understanding of flower evolution and sexual reproduction; hence, it might provide an opportunity to manipulate a plant's reproductive strategy. As pseudovivipary is always closely associated with various environmental factors, the molecular basis of pseudovivipary is still unknown. Here we report mutations of two MADS-box transcription factors that are essential for sexual reproduction and mutations of which lead to stable pseudovivipary in rice.

Results

Characterization of pho mutant

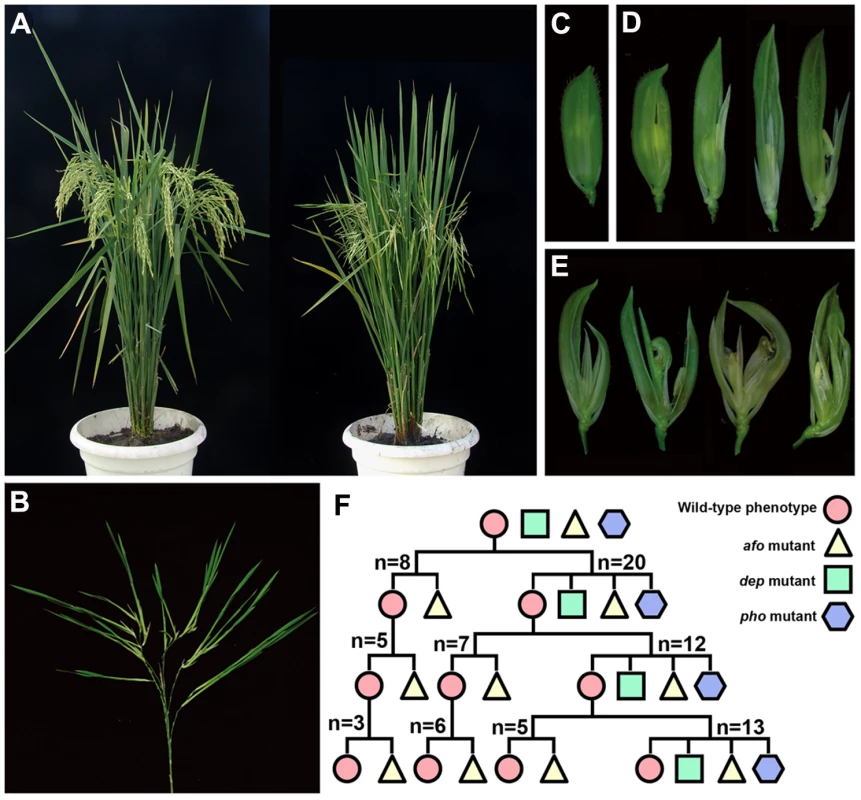

In this study, a naturally occurring mutant showing inflorescence reversion was found in the offspring of an Oryza sativa spp. indica var. Zhongxian 3037. Instead of normal floral organs, this mutant generated new plantlets (Figure 1A and 1B). The plantlets, like normal juvenile plants, generated roots, produced tillers and showed normal vegetative growth when explanted in paddy fields (Figure S1A and S1B). In the subsequent life cycle, plants again displayed inflorescence reversion. Thus, this mutant could be considered to be a complete pseudovivipary mutant in which the reproductive mode has completely changed from sexual to asexual. In fact, this mutant has accomplished six life cycles via this asexual reproductive method. This type of mutation has not been reported before in rice. We named the mutant phoenix (pho) to reflect its stable “never die and reborn anew” phenotype. Two additional mutants were also found in this segregating population. The first mutant was named degenerative palea (dep), and was characterized by shrunken paleas. Paleas in severe dep florets degenerated to glume-like organs that were prone to splitting. The lemmas and glumes in dep florets were slightly elongated (Figure 1D). The second mutant abnormal floral organs (afo) displayed a phenotype opposite to dep, with abnormalities primarily in lemma and the inner three whorls (Figure 1E).

Fig. 1. Phenotypic characterization and genetic analysis of pho, dep, and afo mutants.

(A) The phenotype of wild-type (left) and pho (right) plants. (B) All flowers are replaced by young plantlets in pho panicle. (C) The spikelet of wild-type rice. (D) The spikelets of dep in the order of increasing severity showing the defects of paleas. (E) The spikelets of the afo mutant showing pleiotropic defects in lemmas and the inner three whorls. (F) Genetic analysis of pho, dep, and pho mutants indicates that pho might be a double mutant containing both a Mendelian mutation in DEP and a non-Mendelian mutation in AFO; “n” indicates the line number. In order to examine the genetic basis of the three mutations, seeds of the 28 individual plants showing the normal phenotype from the above population were planted into lines by parent plants. We found that those genotypes self-segregated into two categories. The first category only produced afo and wild phenotype plants, while the second category produced dep, afo, and pho, as well as wild phenotype plants. As the segregation ratios in both categories seemed unclear, seeds of the wild phenotype plants from each category were planted in individual lines for two more generations. Subsequently, all plants in the final generation were counted and analyzed (summarized in Figure 1F). In the first category lines, 35.34% of plants displayed the afo phenotype, while 64.66% of plants exhibited the wild phenotype (n = 232). As the segregation did not follow Mendelian patterns (3∶1 ratio, χ2 (1) = 13.24, P<0. 01), we proposed that afo might be a non-Mendelian mutant. In the second category lines, 28.44% plants showed the afo phenotype, 18.35% plants showed the dep phenotype and 7.34% plants showed the pho phenotype (n = 218). We observed that pho only appeared in the line where afo and dep mutants coexisted. In addition, when we put the wild phenotype plants and afo mutants into one group and dep and pho into another group, the segregation ratio would fit a 3∶1 ratio (162∶56, χ2 (1) = 0.06, P>0.50), indicating that dep might be a Mendelian mutant. Therefore, we further hypothesized that pho might be a double mutant containing both a Mendelian mutation in DEP and a non-Mendelian mutation in AFO.

Single amino acid mutation disrupts the transcriptional activation of OsMADS15 in dep

To understand the molecular mechanism of pseudovivipary in pho, we began by isolating the DEP gene through map-based cloning. The dep mutants from the second category line were crossed to O. sativa spp japonica var. Zhonghua11 to generate a mapping population. In the F2 population, 71 of 302 plants showed the dep phenotype (3∶1 ratio, χ2 (1) = 0.36, P>0.50), confirming that the phenotype of the dep mutant is controlled by a single recessive gene. 2,292 F2 and F3 plants showing the dep phenotype were used to map DEP to a 50-kbp region on the short arm of chromosome 7. All genes within this region were amplified and sequenced. A single nucleotide G to C substitution at position 94 in coding region was found in the first exon of the OsMADS15 in the dep mutant. This substitution results in a change from a MADS-box conserved alanine residue to proline (Figure 2A and Figure S5). The same nucleotide mutation was also found in all the pho mutants analyzed (n = 20), further implying that the mutation of OsMADS15 might be partly responsible for the pho phenotype. To confirm that the loss of function of OsMADS15 is responsible for dep, we utilized an RNA interference approach to down-regulate OsMADS15. Forty transgenic plants expressing an inverted repeat of 317 bases of OsMADS15 were generated in Nipponbare. Among them, 35 plants also displayed the dep degenerative palea phenotype (Figure S1C and S1D). Therefore, we concluded that the phenotype of the dep mutant is indeed caused by mutation in OsMADS15.

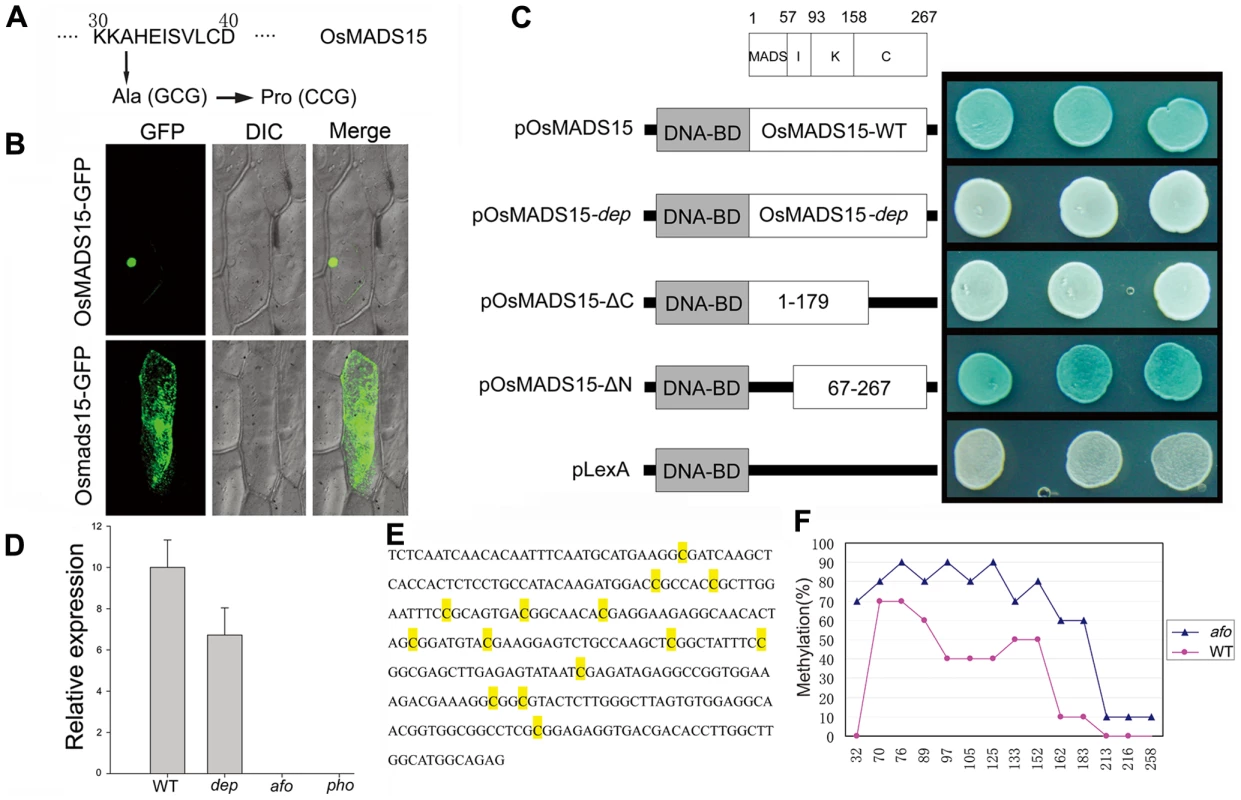

Fig. 2. Molecular mechanisms of dep mutant and afo mutant.

(A) Amino acid mutation corresponding to the nucleotide change in dep. (B) OsMADS15-GFP fusion protein is localized in nucleus while Osmads15 (dep)-GFP fusion protein is localized in cytosol. (C) Transcriptional activation assay of pOsMADS15, pOsMADS15-dep, pOsMADS15△C180-267, pOsMADS15△N1-66, and pLexA. White clones indicate no activation of the reporter gene while blue clones indicate activation of the reporter gene. (D) OsMADS1 expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR analysis in WT, dep, afo, and pho panicles shows the silencing of OsMADS1 in afo and pho. (E) 294-bp sequence in the promoter region of OsMADS1 gene shows different cytosine methylation in WT and afo. The yellow-marked cytosines were found to be methylated in WT or afo. (F) Profiles of DNA methylation in 294-bp region in WT (red line) and afo (blue line) plants. The numbers on the X axis represent cytosine positions in the analyzed region, and the Y axis represents methylation ratios in WT and afo. We found five OsMADS15 transcripts with differing sequences in GeneBank. To identify the WT DEP sequence, we performed RT-PCR and found that our cDNA sequence was identical to GB accession AB003325. This cDNA was used for subsequent analysis. MADS-box proteins are transcription factors, so we conducted experiments to evaluate whether amino acid substitution impaired the transcriptional activation function of OsMADS15 in the dep mutant. OsMADS15 from both WT and dep were fused with GFP protein and transiently expressed in onion epidermal cells as well as rice protoplast cells. The OsMADS15 GFP signal was localized in the nucleus, whereas the dep mutant caused redistribution of OsMADS15 GFP to the cytosol (Figure 2B and Figure S2). Previous study has revealed that the KC region of OsMADS15 (Amino acids of AF058698) does not show any transcriptional activation function [12]. However, a single amino acid substitution, from leucine to histidine mutation, has occurred at position 117 of the amino acids of AF058698. In our study, we found that the OsMADS15 protein itself exhibited transcriptional activator activity. Furthermore, when the MADS domain of OsMADS15 was eliminated, the residual IKC region of OsMADS15 also displayed transcriptional activator activity. However, the mutated protein in dep lost its transcriptional activator activity completely, though the amino acid mutation only occurred in the MADS domain (Figure 2C). Taken together, it is very likely that the mutated OsMADS15 protein has lost its transcriptional activation function in dep.

afo is an epigenetic mutant of OsMADS1, while pho is a spontaneous mutant containing both genetic mutation in OsMADS15 and epigenetic mutation in OsMADS1

From the above genetic analysis, it was deduced that pho and afo were non-Mendelian mutants, so we proposed that they might be epigenetic mutants. Epigenetic mutations are often marked by a reduction or elimination of an associated transcript. Microarray experiments were carried out to investigate whether there were any variations in transcript accumulation between pho and WT young panicles (Table 1). These experiments showed that the transcript levels of multiple genes were altered. Of those altered genes, OsMADS1 (also known as LEAFY HULL STERILE1, LHS1 [13]), was the most significantly altered transcript, with a 2,208-fold reduced expression in pho relative to WT. Real-time PCR was further performed using WT, dep, afo and pho panicle transcripts to confirm this result and to examine whether the afo mutant also showed a reduced expression of OsMADS1 transcripts. As expected, the expression of OsMADS1 was hardly detectable in afo as well as pho (Figure 2D). Additionally, no mutations were detected in the 12,879-bp genomic sequence of the OsMADS1 locus, including the eight exons, seven introns, 2,507-bp upstream sequence and 1,870-bp downstream sequence. We hypothesized that the afo mutant might be caused by an epigenetic modification of OsMADS1. Interestingly, recent studies in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum) revealed that WLHS1-B, one of the homologs of OsMADS1, was silenced by cytosine methylation [14]. To test if this was also the case in rice, we used bisulfate sequencing of exon 1 and the 5′ upstream regions of OsMADS1 in afo to characterize their methylation status. Compared with the WT plants, the promoter region of OsMADS1 in afo was more heavily methylated (from 31.43% to 62.86%), which might contribute to the silencing of OsMADS1 (Figure 2E and 2F).

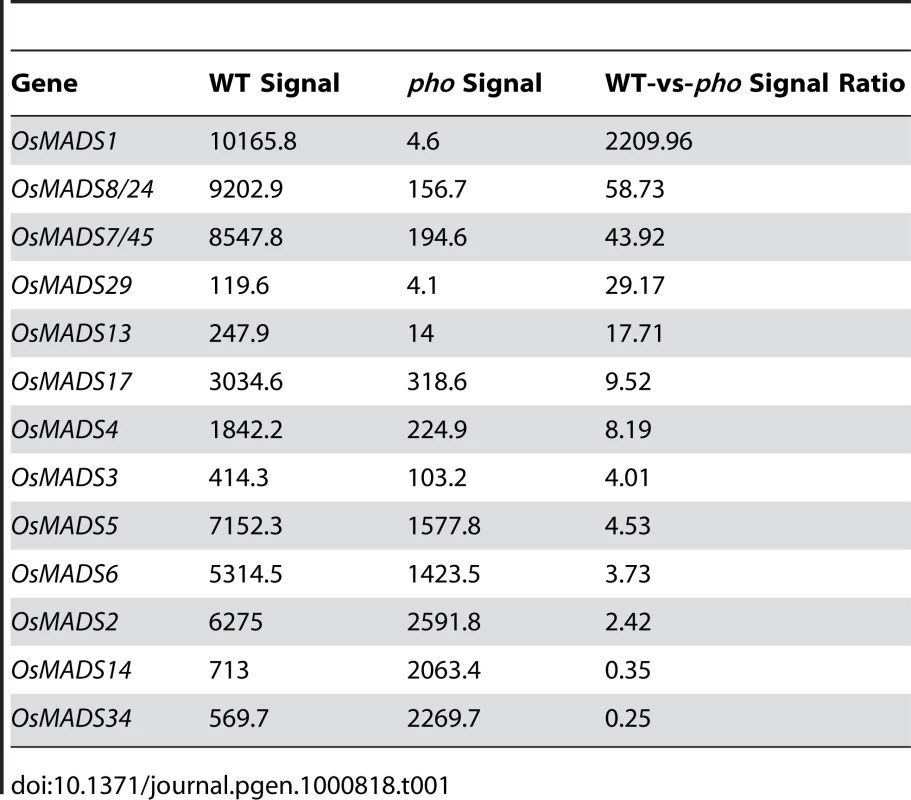

Tab. 1. Expression analysis of MADS-box genes in <i>pho</i> mutant according to the microarray data.

To ascertain whether pho was a dep/afo double mutant, We crossed dep with naked seed rice (nsr), a mutant of the OsMADS1 gene [15], to generate dep/nsr double mutants. In the F2 and F3 population, all the dep/nsr double mutants analyzed (n = 35) showed a similar pseudovivipary phenotype to that of the pho mutants (Figure S3). This double mutant has accomplished three life cycles via asexual reproductive method. So, this result confirmed that pho was a double mutant of Osmads1 and Osmads15.

dep displays pseudovivipary occasionally

The spikelet development of each of the three mutants was further analyzed to explore functions of the two MADS-box genes during spikelet development. Previous studies have characterized OsMADS1 as a SEPALLATA (SEP)-like gene and performed multiple investigations in rice. However, the function of OsMADS1 is still not fully elucidated [13], [15]–[20]. The afo mutant shared many similarities with those severely affected Osmads1 (lhs1) mutants and OsMADS1RNAi plants (Figure 1E): all spikelets were sterile; lemmas were more severely affected than paleas; palea marginal tissues (PMTs) were absent while palea main structures (PMSs) were only slightly effected; lodicules were converted into glume-like organs; and ectopic florets that are indicative of partial reversion had frequently arisen from the parent florets [13],[15],[19],[20]. In summary, the phenotype of afo mutant suggests that OsMADS1 is required for the specification of lemma, PMTs and the three inner whorls [13],[15],[19],[20]. Its pleiotropic defects indicate that OsMADS1 is essential for flower meristem (FM) determinacy [13], [15], [19]–[22].

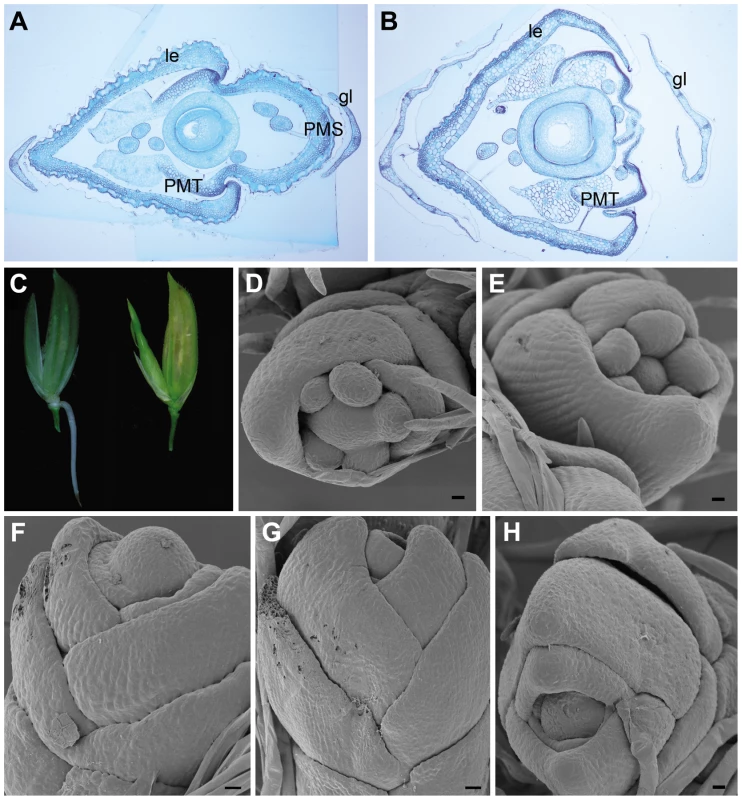

Phylogenetic analyses have characterized OsMADS15 as an APETALA1 (AP1)/FRUITFUL (FUL)-like gene (Figure S4 and Figure S5) [21]–[23]. In addition, previous study has shown that OsMADS15 (RAP1A) RNA was expressed in the incipient floral primordium and later mainly accumulated in empty glumes, lemma, palea and lodicules [23]. However, the function of OsMADS15 is still unclear [21],[22]. The effects of OsMADS15 on cell specifications of all spikelet whorls were histologically examined. In a severely affected dep spikelet, the transformed palea was actually only composed of two PMTs while the PMS was completely lost (Figure 3A and 3B). This implied that the identity of palea was lost in the dep spikelet with the severe phenotype. The lemma in the dep spikelet was also slightly affected, but its identity was still maintained (Figure 3A and 3B, and Figure S6). The glumes of dep spikelets contained many more bundles than the WT glumes, suggesting a possible partial reversion of glumes to leaf-like organs. No obvious difference was found in the inner three whorls, hinting that they are not affected by the mutation of OsMADS15. Thus, OsMADS15 is required for the specification of PMS and empty glumes, those floral organs are just opposite to the affecting whorls of OsMADS1.

Fig. 3. Spikelet morphologies of WT, dep, afo, and pho plants.

(A) Transverse section of the WT spikelet shows normal glumes (gl), lemma (le), palea main structure (PMS) and palea marginal tissue (PMT). (B) Transverse section of the severely affected dep spikelet shows the loss of PMS. (C) Occasional emergence of root at the base of dep rachilla on the lemma side (left) and occasional emergence of tiller between palea and upper empty glume in dep spikelets (right, see also Figure S7). (D,E) SEM of the floral primordium in WT shows that only two empty glumes, lemma (le) and palea (pa) are arranged in alternate phyllotaxis. (F–H) SEM of the floral primordium in pho shows that all lateral organs are arranged in alternate phyllotaxy. Bars in (A,B), 200 µm; bars in (D–H), 10 µm. dep showed a stable degenerative palea phenotype when grown in paddy fields with a normal climate. Unexpectedly, however, we found that, under a continuous rain for several days during its heading stage, roots occasionally emerged from the base of dep rachillas (Figure 3C). Only one root was formed in each spikelet and it merely located at the lemma side (n = 22). These roots would soon degenerate if the spikelets were dried. Interestingly, if the continuous rain occurred after the heading stage, the inner floral organs or developing seeds of dep always got mildewed because of the lack of protection by paleas, but emergence of new shoots was occasionally visible in dep spikelets (Figure 3C and Figure S7A, S7B, and S7C). In contrast to the emerged roots that were only formed on the lemma side, these emerged shoots only appeared between paleas and upper empty glumes on the other side (n = 24). Moreover, prophylls were found on these shoots, indicating that these emerged shoots are actually tillers. These tillers also generated roots, produced new tillers and showed normal vegetative growth when replanted in fields (Figure S7D and S7E). So, dep can also be considered to be an unstable pseudovivipary mutant that was closely associated with environmental factors. In the dep mutant, most floral organs develop normally, demonstrating that OsMADS15 might only play a minor role in the FM determinacy. However, the occasional emergence of roots and tillers in dep implies that the shoot apical meristem (SAM) identity is restored and begins to grow under a suitable environment (continuous rain), so OsMADS15 might also participate in inhibiting SAM formation in incipient floral primordium. However, pseudovivipary has not been observed in DEP RNAi plants that grow in paddy fields; it is probably that the residual transcripts in RNAi plants are sufficient to inhibit SAM formation in incipient floral primordium. Alternatively, pseudovivipary, which is mainly observed in natural plants, might be a dep allele–specific phenomenon.

Finally, the primordium development of pho mutant was also analyzed. In WT, two empty glumes, lemma and palea were arranged in alternate phyllotaxis while stamens and carpel were not (Figure 3D and 3E). In contrast, in the pho mutant, no stamen or carpel was observed and all lateral organs were arranged in alternate phyllotaxis (Figure 3F–3H). As those lateral organs finally grew into true leaves but not simple leaf-like organs, it is obvious that FM at least partially transformed into functional SAM although some following floral genes still expressed at this stage (Table 1).

Discussion

Pseudovivipary of dep and pho occurs in two distinct ways

Morphological studies in other grasses have revealed that pseudovivipary occurs either by proliferation of the spikelet axis or by transformation of the lemma [1],[11]. In most cases, pseudovivipary is achieved by the transformation of the spikelet axis.

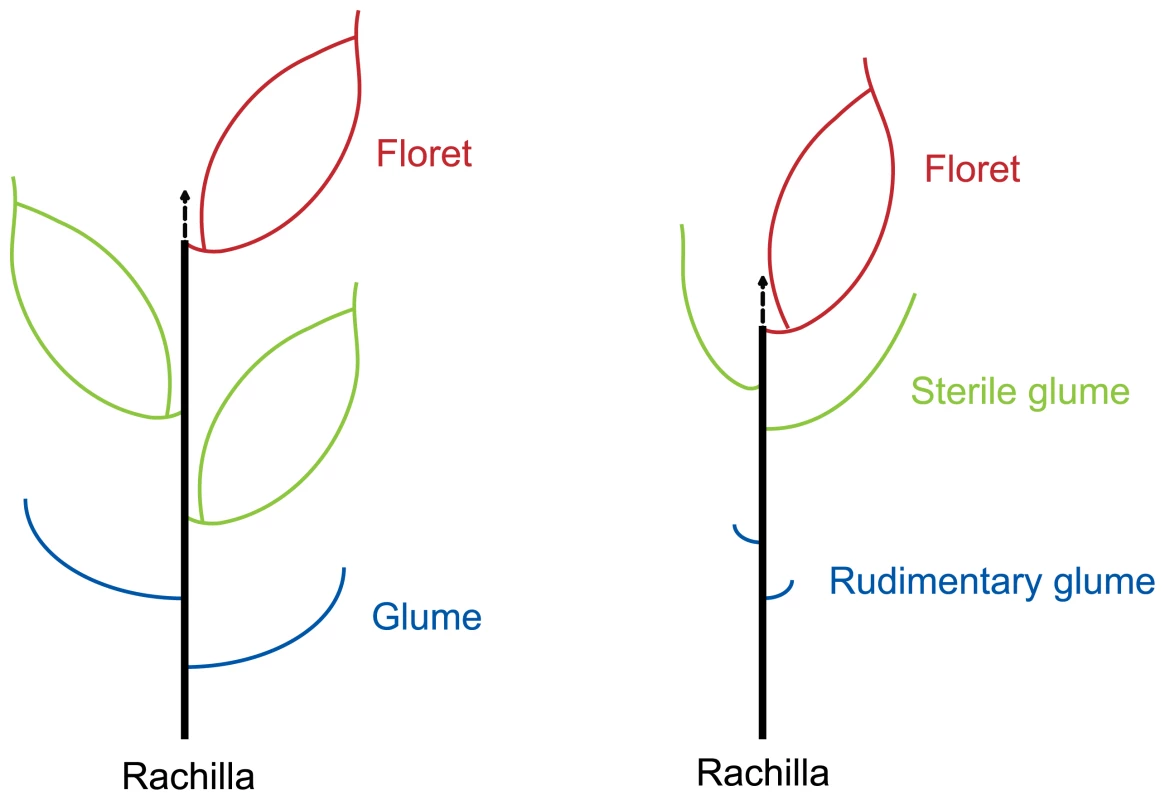

The grass spikelet is a structure consisting of two glumes subtending one or more small florets. The rice spikelet is generally considered to have three florets, which are subtended by two tiny glumes (rudimentary glumes) [21],[24]. The uppermost floret is fertile while the two lower florets are reduced and sterile. The two empty glumes (or sterile lemmas) are considered to be reduced lemmas of two lower florets [21],[24]. So, theoretically, rice spikelet axis is located between the palea and upper empty glume (Figure 4). In this study, new shoots in the dep mutant are merely found between paleas and upper empty glumes. Thus, we conclude that pseudovivipary in the dep mutant is also achieved by the transformation of the spikelet axis.

Fig. 4. Diagrammatic representation of the spikelets of typical grass with three florets (left) and rice (right).

The arrows indicate the spikelet axes, which are transformed to shoots in dep plants. Poa alopecurus and Poa fuegiana, which are non-pseudoviviparous and pseudoviviparous species, respectively, can also be recognized as the same species because of the close affinities between them [11]. The characters of Poa fuegiana have been well described [11]. A detailed comparison of rice dep plant with Poa fuegiana shows that there are many similarities between the two pseudoviviparous plants: the palea is reduced or rudimentary; the lemma is elongated; new shoots are only formed on the palea side; both are not stable pseudoviviparous plants; and pseudovivipary mainly happens under high rainfall conditions. Considering so many similarities, it is very likely that the occurrence of pseudovivipary in Poa fuegiana and rice dep mutant might share the same mechanism. However, the validity of this speculation remains to be verified by molecular investigations on Poa fuegiana.

The pho mutant should be classified into the second type of pseudoviviparous plant since the lemma in pho undergoes elongation to form the first leaf of the propagule. However, pho, which differs from those environment-dependent pseudoviviparous grasses, shows stable pseudovivipary phenotype and is not associated with environmental factors. Till now, to our knowledge, no similar stable pseudoviviparous plant has been reported in nature. If similar stable pseudoviviparous plants are found in nature, they are very likely to be recognized as new species, because of the extreme difference in morphology and reproductive method.

Roles of OsMADS1 and OsMADS15

Early studies have showed that both OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 are expressed in the incipient floral primordium [16]–[18],[23]. Furthermore, OsMADS1 interacts with OsMADS15 in yeast two-hybrid experiments [12]. The defects of their mutants indicate that OsMADS1 might work cooperatively with OsMADS15 to determine FM, but their individual roles are divergent: OsMADS1 mainly works in promoting the determinacy of FM while OsMADS15 mainly functions in inhibiting the formation of SAM in incipient floral primordium. Consistent with those indications, the mutations of both OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 in pho result in a stable inflorescence reversion. In addition, OsMADS1 is required for the specification of lemma, PMTs and three inner whorls. On the contrary, OsMADS15 is required for the specification of PMS and empty glumes. So, it is also probably that all floral organs in the double mutant, pho, lost their modifications and transformed into their basal state, namely, leaves.

It has been shown that both transcripts of OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 are eventually accumulated in lemma and palea, suggesting that OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 might also be involved in the development of lemma and palea [17],[23]. In severely affected Osmads1 spikelets, both lemma and palea are affected, but the lemma is affected to a greater extent, suggesting that OsMADS1 might function as a lemma identity gene [19],[22]. Additionally, PMTs are lost in Osmads1 spikelets, indicating that OsMADS1 is also essential for the specification of PMTs. In contrast, in severely affected Osmads15 spikelets, both lemma and palea are affected, but the palea is affected to a greater extent and PMS is completely lost, implying that OsMADS15 might be mainly involved in the specification of PMS. Collectively, both OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 might control the differentiation of lemma and palea, but their different roles might contribute to the asymmetric development of the first whorl of rice spikelets.

OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 are characterized as SEP-like gene and AP1/FUL-like gene, respectively [12], [13], [15]–[23]. AP1, FUL and SEP1/2/3/4 genes in dicot model plant Arabidopsis are also involved in floral meristem identity determination [25]–[28]. In addition, previous studies in Arabidopsis have transformed floral organs into leaf-like organs [26],[29],[30]. However, transformation of flowers into true plantlets that is indicative of pseudovivipary has not been found in Arabidopsis, but has been reported in many grasses in nature [1]. The difference might be caused by the distinction of floral development between grasses and dicot plants, as well as the diversification of those floral genes during evolution [16],[21],[31].

Is grass flower a modified plantlet meant for reproduction?

More than 200 years ago, Goethe proposed that the floral organs are modified leaves. This belief is supported by the observation that triple mutants lacking the ABC genes in Arabidopsis have a conversion of all floral organs into leaf-like organs [29],[30]. In this study, we revealed that mutations in OsMADS1 and OsMADS15 lead to the transformation of all rice flowers into plantlets that can produce true leaves, thereby further confirming Goethe's hypothesis. The complete transformation of flowers into juvenile plantlets in rice, as well as similar transformations in other grasses, leads us to hypothesize that in grasses a flower may be a modified juvenile plantlet meant for reproduction.

It is widely accepted that sexual reproduction evolves from asexual reproduction, so we speculate that pho might be an atavistic mutant, and plants with similar phenotype might play an important role in the evolution of reproductive strategy from asexual to sexual. The dep mutant, which can produce both flowers and plantlets, is more similar to most natural pseudoviviparous plants than the pho mutant. Thus, its analogous plants might play an intermediate role in this evolution, because such environment-dependent pseudoviviparous plant has the ability not only to reproduce via sexual way under favourable conditions, but also to reproduce via asexual way when the harsh conditions affect its sexual reproduction.

In conclusion, we have shown that dep is a genetic mutant in OsMADS15 while afo is an epigenetic mutant in OsMADS1, and their combination led to stable pseudovivipary. These findings suggest that the two MADS-box genes might play important roles in plant adaptation to various reproductive strategies.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

All plant materials were grown in individual lines in paddy fields to monitor climate-change triggered pseudovivipary. In summer, all materials were planted in Beijing and Yangzhou, while, in winter, all materials were grown in Hainan Island in South China.

Primers

The primers used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Molecular cloning of DEP

To fine map DEP, STS markers (P1–P8) were developed based on sequence differences between indica variety 9311 and japonica variety Nipponbare according to the data published in http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Construction of RNA interference and rice transformation

A 317-bp fragment of OsMADS15 was amplified by PCR with their specific primers; this fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega) and sequentially cloned into the BamHI/SalI and BglII/XhoI sites of the pUCRNAi vector. Subsequently, the stem-loop fragment was cloned into the pCAMBIA2300-Actin vector. The resulting RNAi construct was transformed into an A. tumefaciens strain and used for further rice transformation.

Subcellular localization

The amplified coding region of OsMADS15 of both wild-type and dep was fused with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and cloned into the HindIII/BamHI sites of the vector pJIT163. Those plasmids were bombarded into onion epidermal cells using a PDS-1000/He particle gun (Bio-Rad). The expression constructs were also transfected into rice Nipponbare protoplasts. Twenty hours after transfection, protein expression was observed and images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope.

Transcriptional activation assay

We carried out the transcriptional activation assay using a MATCHMAKER LexA Two-Hybrid system (Clontech). Different length sequences were amplified and fused in frame to the pLexA to construct pOsMADS15, pOsMADS15-dep, pOsMADS15△C180-267 and pOsMADS15△N1-66. All constructs were used to transform the recipient strain EGY48 with p8op-lacZ. Transformants were selected on Ura/His depleted plates at 30°C for 3 days. The activation ability was assayed on Gal/Raf (Ura−/His−)/X-gal to test the activation of the LacZ reporter gene for 3 days.

Affymetrix GeneChip hybridization and data analysis

In order to generate gene expression profiles of WT and the pho mutant, we conducted 57K Affymetrix rice whole genome array. The total RNA of rice panicle (5–8 cm) samples was isolated using TRizol reagent (Invitrogen) and purified using Qiagen RNeasy columns (Qiagen). All the processes for cDNA and cRNA synthesis, cRNA fragmentation, hybridization, staining, and further scanning, were conducted according to the GeneChip Standard Protocol (Eukaryotic Target Preparation, Affymetrix). 5 ug of total RNA was used for making biotin-labeled cRNA targets. 10 ug of cRNA was hybridized for 16 h at 45°C on GeneChip Rice Genome Array. GeneChips were washed and stained in the Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450. GeneChip were scanned using the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner. The information about GeneChip Rice Genome Array (MAS 5.0) could be accessed from Affymetrix website: http://www.affymetrix.com/products_services/arrays/specific/rice.affx. GCOS software (Affymetrix GeneChip Operating Software) was used for data collection and normalization. The overall intensity of all probe sets of each array was scaled to 500 to guaranty that hybridization intensity of all arrays was equivalent, each probe set was assigned with present “P”, absent “A” and marginal “M” and p-value from algorithm in GCOS. The microarray data has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) of NCBI under accession GSE17194.

Phylogenetic analysis

All MADS-box proteins were retrieved by BLAST searches using the conserved M-, I-, K-domain regions (174 amino acids) of OsMADS15 protein (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Protein sequences were aligned using the CLUSTALX 1.83 [32]. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Molecular Evolution and Genetic Analysis (MEGA) package version 3.1 [33].

Morphological analysis

For SEM, samples were fixed overnight at room temperature with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and dehydrated through an ethanol series. Then the samples were replaced by isoamyl acetate, critical point dried, sputter coated with gold, and observed with a scanning electron microscope. For histology, samples were fixed in FAA (5% formaldehyde, 5% glacial acetic acid and 63% ethanol) overnight at 4°C, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, embedded in Technovit 7100 resin (Hereaus Kulzer) and polymerized at room temperature. Transverse sections were performed using an Ultratome III ultramicrotome (LKB), stained with 0.25% toluidine blue (Chroma Gesellshaft Shaud) and photographed using an Olympus BX61 microscope.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from rice young panicles (5–8 cm) using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) as described by the supplier. 3 µg RNA was reverse-transcribed with Oligo-dT(18) primer using the superscript II RNaseH reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). For quantitative real-time RT-PCR, first strand cDNAs were used as templates in real-time PCR reactions using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The amplification of the target genes were analyzed using the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System and Software (PE Applied Biosystems). Ubiquitin was used as a control to normalize all data.

Bisulfite sequencing

Five micrograms genomic DNA isolated from panicles (5–8 cm) was digested with EcoRI and PstI. After centrifugation, pellets were dissolved in 50 µL of water, heated at 95°C for 15 min, and quenched on ice. Fifty microliters of NaOH (3 M) was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by the addition of 565 µL bisulfite solution to the denatured DNA. Samples were treated at 55°C for 20 h. After being purified using a Wizard DNA clean-up system (Promega), 50 µL bisulfite-treated DNA was added with 5 µL NaOH (3 M) and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The Bisulfite-treated DNA was precipitated with ammonium acetate and ethanol, and the pellets were dissolved in 50 µL of water. PCR analysis was performed at 50°C using four primer sets (BSP1-4). PCR products were cloned into PMD18-T vectors. Ten clones of each product were sequenced to determine the methylation ratio. Cytosine methylation was only found in the BSP1 region.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. TookeF

OrdidgeM

ChiurugwiT

BatteyN

2005 Mechanisms and function of flower and inflorescence reversion. J Exp Bot 56 2587 2599

2. BatteyNH

LyndonRF

1990 Reversion of flowering. The Botanical Review 56 162 189

3. ElmqvistT

CoxPA

1996 The evolution of vivipary in flowering plants. Oikos 77 3 9

4. GoebelKE

1905 Organography of plants, especially of the Archegoniata and Spermaphyta. Oxford Clarendon press 1 707

5. CoelhoFF

CapeloC

NevesAC

MartinsRP

FigueiraJE

2006 Seasonal timing of pseudoviviparous reproduction of Leiothrix (Eriocaulaceae) rupestrian species in South-eastern Brazil. Ann Bot (Lond) 98 1189 1195

6. PierceS

StirlingCM

BaxterR

2003 Pseudoviviparous reproduction of Poa alpina var. vivipara L. (Poaceae) during long-term exposure to elevated atmospheric CO2. Ann Bot (Lond) 91 613 622

7. VegaAS

Rúgolo de AgrasarZE

2006 Vivipary and pseudovivipary in the Poaceae, including the first record of pseudovivipary in Digitaria (Panicoideae: Paniceae). South African Journal of Botany 72 559 564

8. Gordon-GrayKD

BaijnathH

WardCJ

WraggPD

2009 Studies in Cyperaceae in southern Africa 42: Pseudo-vivipary in South African Cyperaceae. South African Journal of Botany 75 165 171

9. MiltonSJ

DeanWRJ

RahlaoSJ

2008 Evidence for induced pseudo-vivipary in Pennisetum setaceum (Fountain grass) invading a dry river, arid Karoo, South Africa. South African Journal of Botany 74 348 349

10. BallesterosE

CebrianE

Garcia-RubiesA

AlcoverroT

RomeroJ

2005 Pseudovivipary, a new form of asexual reproduction in the seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Botanica Marina 48 175 177

11. MooreDM

DoggettMC

1976 Pseudo-vivipary in Fuegian and Falkland Islands grasses. Br Antarct Surv Bull 43 103 110

12. LimJ

MoonYH

AnG

JangSK

2000 Two rice MADS domain proteins interact with OsMADS1. Plant Mol Biol 44 513 527

13. JeonJS

JangS

LeeS

NamJ

KimC

2000 leafy hull sterile1 is a homeotic mutation in a rice MADS box gene affecting rice flower development. Plant Cell 12 871 884

14. ShitsukawaN

TahiraC

KassaiK

HirabayashiC

ShimizuT

2007 Genetic and epigenetic alteration among three homoeologous genes of a class E MADS box gene in hexaploid wheat. Plant Cell 19 1723 1737

15. ChenZX

WuJG

DingWN

ChenHM

WuP

2006 Morphogenesis and molecular basis on naked seed rice, a novel homeotic mutation of OsMADS1 regulating transcript level of AP3 homologue in rice. Planta 223 882 890

16. MalcomberST

KelloggEA

2004 Heterogeneous expression patterns and separate roles of the SEPALLATA gene LEAFY HULL STERILE1 in grasses. Plant Cell 16 1692 1706

17. PrasadK

SriramP

KumarCS

KushalappaK

VijayraghavanU

2001 Ectopic expression of rice OsMADS1 reveals a role in specifying the lemma and palea, grass floral organs analogous to sepals. Dev Genes Evol 211 281 290

18. JeonJS

LeeS

AnG

2008 Intragenic Control of Expression of a Rice MADS Box Gene OsMADS1. Mol Cells 26 474 480

19. PrasadK

ParameswaranS

VijayraghavanU

2005 OsMADS1, a rice MADS-box factor, controls differentiation of specific cell types in the lemma and palea and is an early-acting regulator of inner floral organs. Plant J 43 915 928

20. AgrawalGK

AbeK

YamazakiM

MiyaoA

HirochikaH

2005 Conservation of the E-function for floral organ identity in rice revealed by the analysis of tissue culture-induced loss-of-function mutants of the OsMADS1 gene. Plant Mol Biol 59 125 135

21. YamaguchiT

HiranoHY

2006 Function and diversification of MADS-box genes in rice. ScientificWorldJournal 6 1923 1932

22. KaterMM

DreniL

ColomboL

2006 Functional conservation of MADS-box factors controlling floral organ identity in rice and Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 57 3433 3444

23. KyozukaJ

KobayashiT

MoritaM

ShimamotoK

2000 Spatially and temporally regulated expression of rice MADS box genes with similarity to Arabidopsis class A, B and C genes. Plant Cell Physiol 41 710 718

24. BommertP

Satoh-NagasawaN

JacksonD

HiranoHY

2005 Genetics and evolution of inflorescence and flower development in grasses. Plant Cell Physiol 46 69 78

25. FerrandizC

GuQ

MartienssenR

YanofskyMF

2000 Redundant regulation of meristem identity and plant architecture by FRUITFULL, APETALA1 and CAULIFLOWER. Development 127 725 734

26. DittaG

PinyopichA

RoblesP

PelazS

YanofskyMF

2004 The SEP4 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana functions in floral organ and meristem identity. Curr Biol 14 1935 1940

27. BowmanJL

AlvarezJ

WeigelD

MeyerowitzEM

SmythDR

1993 Control of flower development in Arabidopsis thaliana by APETALA1 and interacting genes. Development 119 721 743

28. PelazS

Gustafson-BrownC

KohalmiSE

CrosbyWL

YanofskyMF

2001 APETALA1 and SEPALLATA3 interact to promote flower development. Plant J 26 385 394

29. BowmanJL

SmythDR

MeyerowitzEM

1991 Genetic interactions among floral homeotic genes of Arabidopsis. Development 112 1 20

30. MeyerowitzEM

SmythDR

BowmanJL

1989 Abnormal flowers and pattern formation in floral. Development 106 209 217

31. IkedaK

SunoharaH

NagatoY

2004 Developmental course of inflorescence and spikelet in rice. Breeding Science 54 147 156

32. ThompsonJD

GibsonTJ

PlewniakF

JeanmouginF

HigginsDG

1997 The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 25 4876 4882

33. KumarS

TamuraK

NeiM

2004 MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform 5 150 163

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70Článek Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse ModelČlánek Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin PathwayČlánek Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Irradiation-Induced Genome Fragmentation Triggers Transposition of a Single Resident Insertion Sequence

- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- Modeling of Environmental Effects in Genome-Wide Association Studies Identifies and as Novel Loci Influencing Serum Cholesterol Levels

- Inverse Correlation between Promoter Strength and Excision Activity in Class 1 Integrons

- Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70

- Postnatal Survival of Mice with Maternal Duplication of Distal Chromosome 7 Induced by a / Imprinting Control Region Lacking Insulator Function

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse Model

- Understanding Gene Sequence Variation in the Context of Transcription Regulation in Yeast

- miR-30 Regulates Mitochondrial Fission through Targeting p53 and the Dynamin-Related Protein-1 Pathway

- Elevated Levels of the Polo Kinase Cdc5 Override the Mec1/ATR Checkpoint in Budding Yeast by Acting at Different Steps of the Signaling Pathway

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

- Co-Orientation of Replication and Transcription Preserves Genome Integrity

- A Comprehensive Map of Insulator Elements for the Genome

- Environmental and Genetic Determinants of Colony Morphology in Yeast

- U87MG Decoded: The Genomic Sequence of a Cytogenetically Aberrant Human Cancer Cell Line

- The MCM-Binding Protein ETG1 Aids Sister Chromatid Cohesion Required for Postreplicative Homologous Recombination Repair

- Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

- Differential Localization and Independent Acquisition of the H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 Chromatin Modifications in the Adult Germ Line

- Genetic Crossovers Are Predicted Accurately by the Computed Human Recombination Map

- Collaborative Action of Brca1 and CtIP in Elimination of Covalent Modifications from Double-Strand Breaks to Facilitate Subsequent Break Repair

- Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies as a Novel Susceptibility Gene for Osteoporosis

- and Regulate Reproductive Habit in Rice

- Nonsense-Mediated Decay Enables Intron Gain in

- Altered Gene Expression and DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Cells from Friedreich's Ataxia Patients: Cellular Model of Pathology

- The Systemic Imprint of Growth and Its Uses in Ecological (Meta)Genomics

- The Gift of Observation: An Interview with Mary Lyon

- Genotype and Gene Expression Associations with Immune Function in

- The Elongator Complex Regulates Neuronal α-tubulin Acetylation

- Rising from the Ashes: DNA Repair in

- Mis-Spliced Transcripts of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α6 Are Associated with Field Evolved Spinosad Resistance in (L.)

- BRIT1/MCPH1 Is Essential for Mitotic and Meiotic Recombination DNA Repair and Maintaining Genomic Stability in Mice

- Non-Coding Changes Cause Sex-Specific Wing Size Differences between Closely Related Species of

- Evidence for Pervasive Adaptive Protein Evolution in Wild Mice

- Evolutionary Mirages: Selection on Binding Site Composition Creates the Illusion of Conserved Grammars in Enhancers

- VEZF1 Elements Mediate Protection from DNA Methylation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání