-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaIs Co-Expressed with Closely Adjacent Uncharacterised Genes Spanning a Breast Cancer Susceptibility Locus at 6q25.1

Approximately 80% of human breast carcinomas present as oestrogen receptor α-positive (ER+ve) disease, and ER status is a critical factor in treatment decision-making. Recently, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the region immediately upstream of the ER gene (ESR1) on 6q25.1 have been associated with breast cancer risk. Our investigation of factors associated with the level of expression of ESR1 in ER+ve tumours has revealed unexpected associations between genes in this region and ESR1 expression that are important to consider in studies of the genetic causes of breast cancer risk. RNA from tumour biopsies taken from 104 postmenopausal women before and after 2 weeks treatment with an aromatase (oestrogen synthase) inhibitor was analyzed on Illumina 48K microarrays. Multiple-testing corrected Spearman correlation revealed that three previously uncharacterized open reading frames (ORFs) located immediately upstream of ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97, and C6ORF211 were highly correlated with ESR1 (Rs = 0.67, 0.64, and 0.55 respectively, FDR<1×10−7). Publicly available datasets confirmed this relationship in other groups of ER+ve tumours. DNA copy number changes did not account for the correlations. The correlations were maintained in cultured cells. An ERα antagonist did not affect the ORFs' expression or their correlation with ESR1, suggesting their transcriptional co-activation is not directly mediated by ERα. siRNA inhibition of C6ORF211 suppressed proliferation in MCF7 cells, and C6ORF211 positively correlated with a proliferation metagene in tumours. In contrast, C6ORF97 expression correlated negatively with the metagene and predicted for improved disease-free survival in a tamoxifen-treated published dataset, independently of ESR1. Our observations suggest that some of the biological effects previously attributed to ER could be mediated and/or modified by these co-expressed genes. The co-expression and function of these genes may be important influences on the recently identified relationship between SNPs in this region and breast cancer risk.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001382

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001382Summary

Approximately 80% of human breast carcinomas present as oestrogen receptor α-positive (ER+ve) disease, and ER status is a critical factor in treatment decision-making. Recently, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the region immediately upstream of the ER gene (ESR1) on 6q25.1 have been associated with breast cancer risk. Our investigation of factors associated with the level of expression of ESR1 in ER+ve tumours has revealed unexpected associations between genes in this region and ESR1 expression that are important to consider in studies of the genetic causes of breast cancer risk. RNA from tumour biopsies taken from 104 postmenopausal women before and after 2 weeks treatment with an aromatase (oestrogen synthase) inhibitor was analyzed on Illumina 48K microarrays. Multiple-testing corrected Spearman correlation revealed that three previously uncharacterized open reading frames (ORFs) located immediately upstream of ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97, and C6ORF211 were highly correlated with ESR1 (Rs = 0.67, 0.64, and 0.55 respectively, FDR<1×10−7). Publicly available datasets confirmed this relationship in other groups of ER+ve tumours. DNA copy number changes did not account for the correlations. The correlations were maintained in cultured cells. An ERα antagonist did not affect the ORFs' expression or their correlation with ESR1, suggesting their transcriptional co-activation is not directly mediated by ERα. siRNA inhibition of C6ORF211 suppressed proliferation in MCF7 cells, and C6ORF211 positively correlated with a proliferation metagene in tumours. In contrast, C6ORF97 expression correlated negatively with the metagene and predicted for improved disease-free survival in a tamoxifen-treated published dataset, independently of ESR1. Our observations suggest that some of the biological effects previously attributed to ER could be mediated and/or modified by these co-expressed genes. The co-expression and function of these genes may be important influences on the recently identified relationship between SNPs in this region and breast cancer risk.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women, accounting for more than 400,000 deaths per year worldwide [1]. Approximately 80% of human breast carcinomas present as oestrogen receptor α-positive (ER+ve) disease and ER status is arguably the most clinically important biological factor in all oncology [2]. The major molecular features of breast cancer segregate differentially between ER+ve and ER−ve tumours [3], [4]. Tumours which express ERα have been termed luminal type [3], [5] and are associated with response to antioestrogen therapy and improved survival, although the mechanisms by which oestrogen receptor dictates tumour status are poorly understood.

Recent genome wide studies have identified SNPs around C6ORF97, an open reading frame (ORF) immediately upstream of the gene encoding ER (ESR1) to be associated with increased risk of breast cancer. Zheng et al. found that heterozygosity at rs2046210, a SNP in the region between C6ORF97 and ESR1, increased breast cancer risk by an odds ratio of 1.59 in a Chinese population and that this risk was also present in a European population, albeit to a weaker extent [6]. Easton and colleagues confirmed the risk associated with this SNP and reported an at least partly independent risk associated with a second adjacent SNP (rs3757318) in intron 7 of C6ORF97 [7]. Using ancestry-shift refinement mapping, Stacey et al. closed in on the identification of the pathogenic variant and found that the risk allele of a novel SNP in this region (rs77275268), disrupts a partially methylated CpG sequence within a known CTCF binding site [8]. More recently, two further studies have confirmed an association with the region [9], [10]. Our studies have revealed unexpected relationships in the expression patterns in breast carcinomas between ESR1, C6ORF97 and the two genes immediately upstream (C6ORF211 and C6ORF96 [RMND1]).

Oestrogenic ligands, predominantly oestradiol, are the key mitogens for ER+ve breast cancer. In recent years, high throughput genomic technologies have revealed significant numbers of genes that are expressed in response to oestradiol stimulation in vitro [11]–[13] and downregulated in response to oestrogen deprivation in tumours [14]–[16]. Similarly, the transcriptional targets of ERα have been characterised in detail using genome wide chromatin interaction mapping in MCF7 cells [17], [18]. Key oestrogen responsive genes such as TFF1 and GREB1 have been shown to be highly responsive to oestradiol stimulation in cell culture models through the binding of ERα to their promoters [19], [20]. Additional genes have been found in hierarchical clustering analyses of ER+ve and ER−ve tumours as part of the so-called “luminal epithelial” gene set characterized by the expression of genes typically expressed in the cells that line the ducts of normal mammary glands including GATA3 and FOXA1 [12]. However, the correlates of ESR1 within an exclusively ER+ve group and the inherent heterogeneity within an exclusively ER+ subgroup remain poorly defined.

Modern, non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are widely used, effective treatments for ER+ve breast cancer [21], [22] and are also excellent pharmacological probes for oestrogen-dependent processes in vivo because of their specificity and highly effective suppression of oestrogen synthesis. In this study, we found that the expression of genes in the region immediately upstream of ESR1 associate strongly with ESR1 expression in ER+ve primary breast cancers before and after AI treatment and uncover evidence that these associations might impact upon the biological and clinical importance of ERα.

Results

ESR1 expression is correlated with three open reading frames on chromosome 6 in tumours

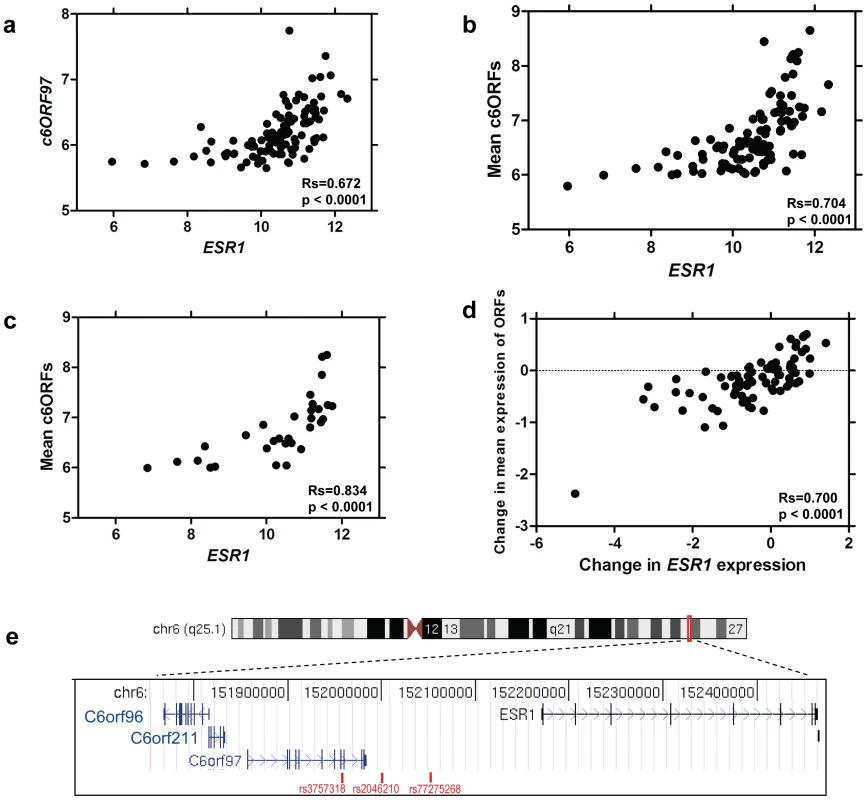

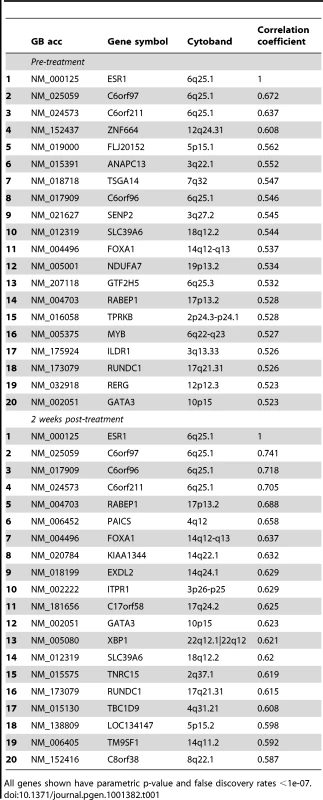

To investigate correlates of ESR1, expression profiles were derived from pairs of 14-guage core cut biopsies before and after 2 weeks' treatment with 1 mg/d anastrozole, an AI, from 104 patients with ER+ve primary breast cancer [23]. Genes whose expression correlated with expression of ESR1 levels pre-treatment were identified (Spearman corrected for multiple testing at false discovery rate <1×10−7, Table 1 pre-treatment). The mRNA species most highly correlated with ESR1 were chromosome 6 ORF 97 (C6ORF97, Rs = 0.67) (Figure 1a), followed by C6ORF211. Other notable inclusions amongst the top 20 most correlated genes included well-established ER-associated genes such as FOXA1, MYB and GATA3, plus C6ORF96, also known as RMND1 (Required for Meiotic Nuclear Division 1 homolog). The mean pre-treatment expression of the three ORFs was highly correlated with ESR1 (Rs = 0.70, Figure 1b). After 2 weeks' AI treatment, the top three genes correlating with ESR1 were C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 (Rs>0.7 for all, Table 1 two weeks post-treatment). These three ORFs are all located less than 0.5 MB upstream of the ESR1 start site on the q arm of chromosome 6 (Figure 1e). The expression of other genes located within a 50 MB region surrounding ESR1 were not correlated with ESR1 expression (Rs<0.25) (Table S1).

Fig. 1. Correlation of ESR1 expression and oestrogen-responsive gene expression.

a. Scatterplot of relationship between expression of ESR1 and C6ORF97 in baseline biopsies. b. Correlation between expression of ESR1 and the mean of C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 in baseline biopsies. c. Correlation between ESR1 and the mean of C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 with samples with measured copy number variations shown omitted. d. Scatterplot of relationship between change in ESR1 and the mean change in C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 e. Location of open reading frames, ESR1 and breast cancer associated SNPs on chromosome 6q25.1. Tab. 1. Genes positively correlated with ESR1 gene expression ranked according to Spearman correlation.

All genes shown have parametric p-value and false discovery rates <1e-07. The correlation was present in all of five published microarray data sets of ER+ve breast cancer in which the C6orfs were included on the array (Table 2). The expression of the three ORFs was lower in ER−ve than ER+ve tumours in the Wang dataset [24] (p = 0.002). No significant correlation was found in the ER−ve subgroup of this dataset. This may be a characteristic of ER−ve tumours or, alternatively, the measurement error associated with low levels of ESR1 transcript could preclude detection of a significant correlation in microarray data.

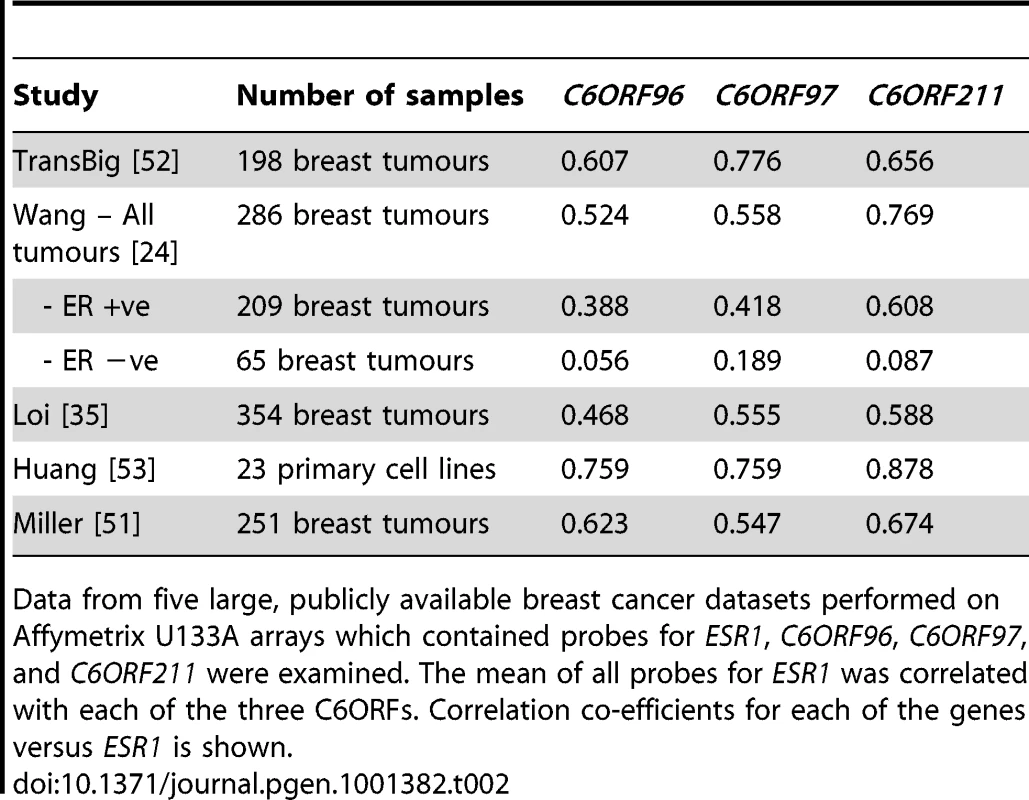

Tab. 2. Correlations in other breast cancer datasets.

Data from five large, publicly available breast cancer datasets performed on Affymetrix U133A arrays which contained probes for ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97, and C6ORF211 were examined. The mean of all probes for ESR1 was correlated with each of the three C6ORFs. Correlation co-efficients for each of the genes versus ESR1 is shown. Correlation between ESR1 and the C6orfs is not explained by amplification

Amplification of the ESR1 locus has been reported inconsistently [25], [26]. To determine whether the ESR1/C6ORFs correlation may be the result of underlying genomic co-amplification or deletion events, copy number (CN) status of ESR1 and the C6orfs was examined using array CGH analysis (resolution 40–60 kb) [27] on DNA from the 44 tumour samples from which adequate further tissue was available. One tumour was shown to be amplified and eight showed gains at ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211, while four showed losses at all four loci. One was measured as having loss of C6ORF96, C6ORF211 and part of C6ORF97. While there was some correlation between CN and transcription of the four genes (Figure S1), CN alterations did not explain the correlation between ESR1 and the C6orfs. In fact, when samples with identified CN changes were removed from the dataset, the correlation between ESR1 and mean C6orf expression levels strengthened rather than weakened (Rs = 0.83) (Figure 1c), suggesting that transcriptional co-regulation rather than genomic changes is more likely to underlie ESR1/C6ORF co-expression.

Change in ESR1 expression upon aromatase inhibitor treatment is correlated with change in C6orf expression

To assess whether the correlation in ESR1/C6ORF expression seen in pre-treatment biopsies is reflected in a concordant change in expression of these genes upon treatment, the relationship between the magnitude of change of each of these genes was investigated. Change in expression of ESR1 induced by aromatase inhibitor treatment over 2 weeks was strongly correlated with change in the C6orfs (Rs = 0.70) (Figure 1d). Given that this short duration of treatment, which has no measurable impact on cellularity or tumour size, is unlikely to facilitate DNA copy number changes throughout the sample this supports the probability that the co-regulation of these genes is at a transcriptional level.

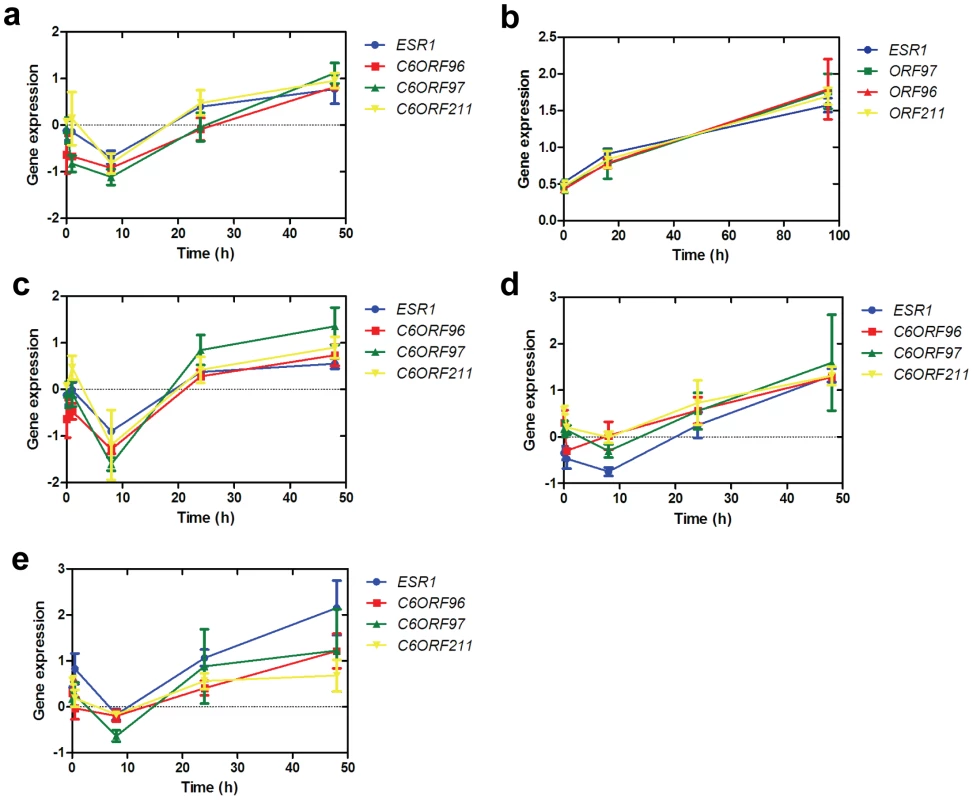

Expression of ESR1 and the C6orfs are correlated in MCF7 and BT-474 cells in vitro

To determine whether the ESR1/C6ORF correlations were maintained in vitro, transcript levels of ERα and the three C6orfs were measured in oestrogen-deprived MCF7 cells and lapatinib-treated BT-474 cells over a 48 - and 96-hour period, respectively. These treatments are both known to have significant effects on the expression of ESR1. Lapatinib has been shown to increase ERα in BT-474 cells [28], [29], potentially via loss of Akt and de-repression of FOXO3a. This provides a useful model for manipulation to test the correlation between ESR1 and the C6orfs in vitro. Conversely, absence of oestradiol leads to a short-term reduction in ER expression [30]. Expression of all four genes followed a similar time-course of expression and was highly correlated (Figure 2a and 2b).

Fig. 2. Correlation of C6orf expression in vitro.

a. Timecourse of expression of ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 in MCF7 cells cultured in the absence of oestradiol. Each gene is normalized to the mean of two housekeeping genes, TBP and FKBP15. b. Timecourse of expression of ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 in BT-474 cells after addition of lapatinib. c. Timecourse of expression of ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 in MCF7 cells cultured with the addition of ICI 182,780. d. Analysis of expression of nascent ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 in MCF7 cells. e. Analysis of expression of nascent ESR1, C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 in MCF7 cells treated with ICI. Points represent the mean of three triplicate samples ± SEM. ICI 182,780 (ICI) is a steroidal pure anti-oestrogen which causes ERα expression to be suppressed and downregulated [31], [32]. Treatment of MCF7 cells with ICI did not affect ORF expression or their correlation with ESR1 (Figure 2c). To confirm that the observed correlation was not being influenced by RNA transcribed prior to the addition of ICI, we also measured newly synthesised nascent RNA using PCR amplicons designed to cross an exon/intron boundary [33]. This analysis revealed that nascent transcripts for ESR1 and the C6orfs remained correlated in both the presence and absence of ICI. The observation that transcription of the genes remains strongly correlated in the presence of ICI suggests that transcriptional regulation by ERα is not the main driver of the ESR1/C6ORF co-expression.

Knockdown of C6ORF211 by siRNA induces a reduction in proliferation in MCF7cells

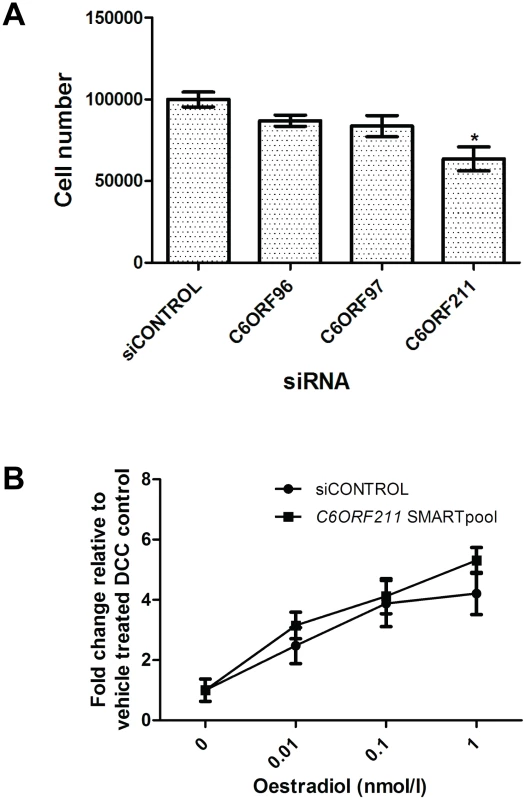

The effect of reducing expression of each C6orf on cell proliferation was determined by transfecting siRNA SMARTPOOLs directed against each ORF into MCF7 cells. In cells grown in both E2-containing media and without E2, all three siRNAs reduced transcript levels of their target ORF to <30% of levels in cells transfected with the control non-targeting siRNA pool. Levels of ESR1, and the non-targeted ORFs were unaffected by the SMARTpool's (Figure S2) while ESR1-SMARTpool siRNA led to a reduction in levels of all three C6orfs (Figure S3). Immunoblotting with a polyclonal antibody raised against a polypeptide of the predicted product of C6ORF211 showed an 86% reduction at the protein level (Figure S4). Cells transfected with C6ORF211 siRNA showed a mean 36% reduction in cell number (p<0.0001) over four separate repeat experiments (Figure 3A). C6ORF211 knockdown had no effect on oestrogen-dependent proliferation (Figure 3B). Deconvolution of the SMARTPOOL showed that the four constituent siRNAs had a reproducible anti-proliferative effect when compared with scrambled control siRNA (Figure S5). No consistent alteration in proliferation was observed in cells transfected with siRNAs directed against C6ORF96 or C6ORF97 (Figure 3A).

Fig. 3. Exploration of the function of the C6orfs in MCF7 cells.

a. Wild type-MCF7 cells were stripped of steroid for 48 hours then transfected with either control siRNA, siRNA SMARTpool for C6ORF96, C6ORF97 or C6ORF211. b. Stripped MCF7 cells were transfected with C6ORF211 siRNA SMARTpool and 48 hours post transfection these were treated with increasing concentrations of oestradiol. After 6 days, proliferation in response to siRNA knockdown was established by change in cell number using a Coulter counter. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of four separate repeats of the experiment. Oestradiol-dependent proliferation is shown as fold change relative to cells with no added oestradiol. C6ORF211 correlates with proliferation and clinical outcome in tumours

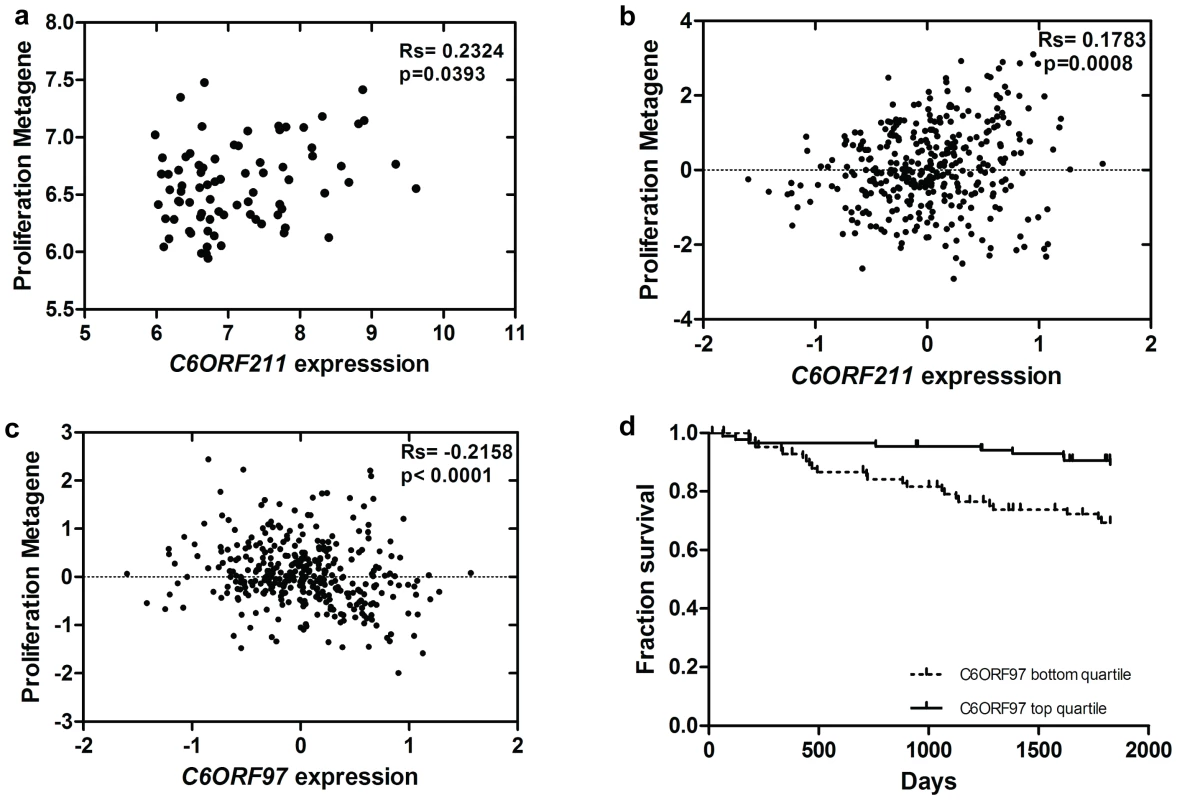

To determine whether the association between C6ORF211 expression and proliferation seen in cultured cells is reflected in tumours, the relationship between C6ORF211 expression and a metagene composed of known proliferation-associated genes [34] was investigated. In baseline biopsies, levels of C6ORF211 but not ESR1 correlated significantly with proliferation (C6ORF211, Rs = 0.23, p = 0.04; ESR1, Rs = −0.01, p = ns) (Figure 4a), suggesting that C6ORF211 is more strongly associated with proliferation than ESR1. Correlations were also observed with a number of well-known proliferation-associated genes (Table S2). The relationship with proliferation was validated in data from a set of 354 ER+ve tumours [35] (Rs = 0.18, p = 0.0008) (Figure 4b) and the 209 ER+ve tumours from the Wang dataset [24] (Rs = 0.21, p = 0.004). Consistent with the findings in our own data, ESR1 was not significantly correlated with the proliferation metagene in either of the publicly available datasets (Loi, Rs = −0.03, p = ns; Wang, Rs = 0.02, p = ns). In contrast, C6ORF97 showed an independent, reproducible negative correlation with proliferation, in our dataset (Rs = −0.19, p = 0.05) and in the Loi (Rs = −0.22, p<0.0001) (Figure 4c) and ER+ve Wang datasets (Rs = −0.24, p = 0.0007).

Fig. 4. Association between C6orf expression, proliferation, and outcome in tumours.

a. Relationship between C6ORF211 expression and expression of proliferation metagene in 104 breast cancers. b. Relationship between C6ORF211 expression and expression of proliferation metagene in 354 breast cancers from the Loi dataset. c. Relationship between C6ORF97 expression and expression of proliferation metagene in the Loi dataset. d. Kaplan–Meier curve representing the fraction relapse-free survival comparing the lowest quartile of C6ORF97 expression with the highest in the Loi dataset. To determine whether the relationship of the ORFs with proliferation is related to clinical outcome, recurrence free survival (RFS) in tamoxifen-treated patients was investigated for association with C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 expression. Despite the fact that in the Loi dataset ESR1 was not predictive of a significant difference in survival over 5 years [36], the lowest quartile of C6ORF97 was associated with significantly higher risk of recurrence (HR = 3.1, p = 0.0014) (Figure 4d). A similar trend was observed in untreated ER+ve tumours from the Wang dataset [24], although this was not significant (HR = 1.6, p = 0.16) (Figure S6a). C6ORF211 was not significantly associated with RFS (Figure S6b and S6c).

Discussion

Our observation of a previously unreported transcriptional activity hub in the ESR1/C6ORF region of 6q25.1 has implications for recently identified associations between SNPs in the ESR1 region and breast cancer risk, as well as broader implications for the biological and clinical importance of ERα in established breast cancer. A number of SNPs, including rs3757318 within intron 7 of C6ORF97 [7], have been associated with breast cancer risk but the causative variant and mechanism remain undefined [6]–[10]. In an attempt to identify the pathogenic variant, Stacey and colleagues recently reported that GG homozygotes at rs9397435, located immediately downstream of C6ORF97, may express higher mean levels of ESR1 and that the rs9397435 [G] allele conferred significant risk of both hormone receptor positive and hormone receptor negative breast cancer in European and Taiwanese patients [8]. The association of a SNP in this region with ER expression is consistent with findings from our own group which have revealed that the variant genotype of SNP rs2046210 is associated with increased ERα expression as measured by immunohistochemistry [37]. The findings reported in this paper suggest that, due to their high degree of correlation with ESR1, levels of C6ORF97, C6ORF96 and C6ORF211 are also likely to correlate with the rs2046210 and rs9397435 genotype. Consequently, these genes may be involved in the pathogenesis of the variant SNPs and could explain the apparent anomaly noted by Stacey and colleagues in that the SNPs predispose to both hormone receptor positive and negative disease.

To date, analysis of ESR1 co-expressed genes has focussed on genes which are also downstream targets of the oestradiol-activated transcription factor activity of ERα such as FOXA1, TFF1 and GATA3. High throughput technologies have identified numerous classical and novel ERα-dependent targets of oestradiol [11], [17]. This association with the expression of ORFs has, however, not been reported other than by ourselves in abstract form [38].

The transcriptional correlation between ESR1 and these ORFs is highly statistically significant in our dataset, and in all of the publicly available datasets we examined. In our own patient cohort, we showed that two weeks' treatment with anastrozole induces a concomitant change in ESR1 and the C6orfs and a yet stronger correlation in their expression. Genomic amplification does not account for the correlations. This suggests that transcriptional co-regulation rather than major genomic rearrangement is likely to underlie their co-expression. To our knowledge, a transcriptional activity hub surrounding a major cancer related gene has not previously been identified.

The observation that the four transcripts remain correlated over a short timecourse in MCF7 and BT474 cells further supports the idea that the co-regulation of these genes is likely to occur at a transcriptional level. Given that ERα can autoregulate its own transcription by binding to an oestrogen responsive element (ERE) in its promoter [17], [39], the possibility that ERα could co-regulate itself and the C6orfs provides an attractive potential explanation for the correlation. We tested this hypothesis by treating MCF7 cells with the ERα antagonist ICI in the absence of E2. Our finding that the nascent transcripts of ESR1 and the three C6orfs remain correlated in the presence of ICI (Figure 2c) suggests that this co-regulation is not dependent on ERα transcriptional activation.

Regulation of the steady-state level of ERα in breast cancer cells is a complex phenomenon that includes transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms [40]–[42]. C6ORF96 is transcribed off the opposite DNA strand to ESR1 (Figure 1e), therefore excluding the possibility that ESR1 and the ORFs are transcribed as a single polycistronic mRNA. Recent genome-wide mapping experiments have revealed the importance of chromatin organisation for gene expression [18], [43] suggesting that 3-D chromatin arrangement could represent a potential explanation for C6ORF/ESR1 co-expression. However, analysis of the data produced by Fullwood and colleagues [18] shows that C6ORF96, C6ORF97 and C6ORF211 are not encompassed by an ERα-bound long-range chromatin loop. Nevertheless, it remains possible that a loop driven by an alternative transcription factor could explain the transcriptional activity in this area.

At the nucleotide level, all three ORFs show some homology with ESR1, suggesting they may have arisen from gene duplication events [44]. C6ORF97 encodes a 715 amino acid coiled-coil domain-containing protein that is conserved across 11 species [45] while C6ORF211 is a member of the UPF0364 protein family of unknown function and is also conserved across multiple species [45]. Confocal analysis revealed that the protein encoded by C6ORF211 was expressed mainly in the cytoplasm and did not co-localize with ER (Figure S7). In a proteomic screen it has been found to interact with SAP18, a Sin3A-associated cell growth inhibiting protein [46].

This reported interaction with a growth inhibitory protein could explain our observation that knockdown of C6ORF211 induces suppression of proliferation in cultured cells. This association is mirrored in tumours, where a proliferation metagene correlates significantly with C6ORF211. Conversely, C6ORF97 expression correlates negatively with expression of the proliferation metagene and high C6ORF97 predicts for improved disease-free survival in a tamoxifen-treated published dataset, independently of ESR1 (Figure 4d). As high ESR1 has previously been shown to be associated with improved outcome on endocrine therapy [47], this raises the possibility that, given the observed correlation of C6ORF97 with ESR1, some of this association with outcome could be attributable to C6ORF97.

The high degree of correlation between ESR1 and the C6orfs has significant potential implications for our interpretation of ER levels and therapy of ER+ve breast cancers. As a transducer of mitogenic oestrogen signalling, disruption of ER represents a key target of therapies for ER+ve breast cancer, including tamoxifen and fulvestrant. Our data shows that C6ORF211 and C6ORF97 may contribute to the proliferative phenotype of ER+ve tumours, yet these proteins are unlikely to be affected by therapies targeted directly at ERα. Consequently, these proteins may represent potential targets for synergistic therapies in patients with high levels of C6orf expression or targets for breast cancer prevention. In addition, along with further research these relationships could shed light on recent associations between breast cancer risk and SNPs in the region.

Materials and Methods

Patient samples

Core-cut tumor biopsies (14-gauge) were obtained from 112 postmenopausal women with stage I to IIIB ER+ early breast cancer before and after two-weeks' anastrozole treatment in a neoadjuvant trial [23]. This study received approval from an institutional review board at each site and was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki [48] and International Conference on Harmonization/Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before participation. Tissue was stored in RNAlater at −20°C. Two 4 µm sections from the core were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to confirm the presence of cancerous tissue and the histopathology and six 8 µm sections were retained for microarray CGH analysis (see below). Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen, Sussex, UK). RNA quality was checked using an Agilent Bioanalyser (Santa Clara, CA, USA): samples with RNA integrity values of less than 5 were excluded from further analysis. ER status and Ki67 values by immunohistochemistry were already available [23].

Gene expression analysis and data pre-processing

RNA amplification, labelling and hybridization on HumanWG-6 v2 Expression BeadChips were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (http://www.illumina.com) at a single Illumina BeadStation facility. Tumor RNA of sufficient quality and quantity was available to generate expression data from 104 pre-treatment biopsies. Data was extracted using BeadStudio software and normalized with variance-stabilizing transformation (VST) and Robust Spline Normalisation method (RSN) in the Lumi package [49]. Probes that were not detected in any samples (detection p value >1%) were discarded from further analysis.

Data analysis

Multiple correlation analysis was performed in BRB-Array Tools (http://linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools.html). A statistical significance level for each gene for testing the hypothesis that the Spearman's correlation between expression of ESR1 and other genes was zero was calculated and p-values were then used in a multivariate permutation test [50] from which false discovery rates were computed. Other statistical analyses were performed in SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), S-PLUS (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA) and Graphpad Prism (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Multivariable analysis was performed in a forward stepwise fashion, the most significant additional variable (satisfying p<0.05) being added at each stage. Cases with missing values for any of the variables in the model were excluded from analysis.

Analysis of publicly available datasets

For analysis of the breast cancer datasets from public resources the publicly available normalised gene expression data and clinical data were retrieved from Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (‘Wang’ dataset [24], n = 286;GEO, accession number GSE2034) or obtained from the authors (‘Loi’ dataset [35], n = 354 tamoxifen-treated tumours composed of GEO, accession numbers GSE9195, GSE6532 and GSE2990; combined normalised dataset received courtesy of Dr Christos Sotiriou). Correlations between ESR1 and the C6orfs in the ‘Miller’ [51] (n = 251), ‘TransBig’ (n = 198) [52] and Huang [53] (n = 23 cell lines) were calculated using the correlation analysis tool in Oncomine (http://www.oncomine.org).

Data from the 72 genes comprising the proliferation metagene was retrieved from tumours from the Wang and Loi datasets and proliferation metagene scores were calculated as described previously [54]. Spearman correlation between the proliferation metagene and ESR1 and the C6orfs was calculated in Graphpad Prism. Survival analysis was carried out in these datasets using the quartiled expression of the C6orfs and the endpoints of recurrence free survival or time to relapse, according to the original publication.

DNA extraction

Five 8 µm sections from frozen core biopsies were mounted onto Superfrost glass slides, stained with nuclear fast red, and microdissected with a sterile needle under a stereomicroscope to obtain a percentage of tumor cells >75% as described previously [55]. Genomic DNA was extracted as described previously [55]. The concentration of the DNA was measured with Picogreen according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen).

Array CGH analysis

The 32K bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) re-array collection (CHORI) tiling path aCGH platform used for this study was constructed in the Breakthrough Breast Cancer Research Centre [55]. DNA labelling, array hybridisations, image acquisition and filtering were performed as described in Natrajan et al. [56]. Data were smoothed using the circular binary segmentation (cbs) algorithm [27]. A categorical analysis was applied to the BACs after classifying them as representing gain, loss or no-change according to their smoothed Log2 ratio values as defined [56].

Cell culture

MCF7 cells were routinely maintained in phenol red free RPMI1640 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and oestradiol (1 nM). Cells were passaged weekly and medium replenished every 48–72 hours. In the case of BT474, cell monolayers were cultured in phenol red containing medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum. Cell lines were shown to be free of mycoplasma by routine testing.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA from treated MCF7 and BT-474 cells was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All RNA quantification was performed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA Nano LabChip Kits (Agilent Technologies, Wokingham, Berkshire, UK). RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen), and random primers. Twenty nanograms of resulting cDNA of each sample was analyzed in triplicates by qRT-PCR using the ABI Perkin-Elmer Prism 7900HT Sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Taqman gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) were used to quantitate processed transcripts of ESR1 (Hs01046818_m1), C6ORF96 (Hs00215537_m1), C6ORF97 (Hs01563344_m1), C6ORF211 (Hs00226188_m1), which were normalized to two housekeeping genes, FKBP15 (Hs00391480_m1) and TBP (Hs00427620_m1). These housekeepers were selected from a previously published list of appropriate reference genes for breast cancer [57]. Custom assays using primers designed to span intron-exon boundaries were used to measure nascent RNA (Table S3). Gene expression was quantified using a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of reference cDNA from a pooled breast cancer cell line RNA.

Immunoblots

Cell monolayers were washed with cold PBS twice and collected by scraping. Cell pellets were lysed in extraction buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as described previously [30]. Membranes were blocked and probed with a polyclonal antibody directed against the predicted peptide (amino acids 368–382) of C6orf211 (Eurogentec, Southampton, UK) and anti β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK) using the methods described previously [58]. Quantification of immunoblots was performed using the NIH ImageJ software, and immunoblots were normalized to actin.

Immunofluorescence and confocal studies

Cells were grown on glass coverslips in standard growth medium. Cells were fixed and incubated in the presence of primary antibodies as described previously [58]. Coverslips were washed with PBS and cells were incubated in the presence of appropriate Alexa Fluor 555 (red) or Alexa Fluor 488 (green)-labeled secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) diluted 1∶1000 for 1 hr. Cells were washed in PBS and nuclei (DNA) were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen) diluted 1∶10000. Coverslips were mounted onto glass slides using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK). Images were collected sequentially in three channels on a Zeiss LSM710 (Carl Zeiss Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, UK) laser scanning confocal microscope at the same magnification (×63 oil immersion objective).

Cell proliferation assays

Cell lines were depleted of steroids for 3 days by culturing in DCC-medium [59], seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well for MCF7 and 4×104 cells per well for BT474, monolayers were allowed to acclimatize for 24 h before treatment with drug combinations indicated for 6 d with daily changes. Cell number was determined using a Z1 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter). Results were confirmed in a minimum of three independent experiments, and each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Effect of oestradiol and ICI182780 on ORF RNA expression

Wt-MCF7 cells were stripped of steroid for 3 days as described above. Cells were subsequently seeded into 12 well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well. After 24 hours monolayers were treated with vehicle (0.01% v/v ethanol), oestradiol (1 nM) or ICI182780 (10 nM) for the time intervals indicated. RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and subjected to qRT-PCR as described.

SiRNA knockdown of ORFs

Wt-MCF7 cells were stripped of steroid for 24 hours in DCC-medium. Stripped cells were subsequently seeded into 12 well plates at a density of 2×104 cells/well for proliferation assays or 1×105 cells/well for RNA expression analysis. After 24 hours monolayers were transfected with 100 nM of either siRNA against C6ORF96, C6ORF97, C6ORF211 or control siRNA using DharmaFECT 1 reagent (Dharmacon, Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK). Medium was then replenished the following day and cells were allowed to acclimatise for a further 24 hours. After 24 hours samples were taken for RNA expression analysis. For analysis of oestrogen-dependent proliferation, the monolayers were treated with increasing concentrations of oestradiol (0.01, 0.1 or 1 nM) 48 hours post transfection. The remaining plates were treated daily with the treatments indicated for 6 days before carrying out cell counts as described above.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. ParkinDM

BrayF

FerlayJ

PisaniP

2005 Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55 74 108

2. DowsettM

DunbierAK

2008 Emerging biomarkers and new understanding of traditional markers in personalized therapy for breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14 8019 8026

3. PerouCM

SorlieT

EisenMB

van de RijnM

JeffreySS

2000 Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 406 747 752

4. HammesSR

LevinER

2007 Extranuclear steroid receptors: nature and actions. Endocr Rev 28 726 741

5. SorlieT

TibshiraniR

ParkerJ

HastieT

MarronJS

2003 Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 8418 8423

6. ZhengW

LongJ

GaoYT

LiC

ZhengY

2009 Genome-wide association study identifies a new breast cancer susceptibility locus at 6q25.1. Nat Genet 41 324 328

7. TurnbullC

AhmedS

MorrisonJ

PernetD

RenwickA

2010 Genome-wide association study identifies five new breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nat Genet 42 504 7

8. StaceySN

SulemP

ZanonC

GudjonssonSA

ThorleifssonG

2010 Ancestry-Shift Refinement Mapping of the C6orf97-ESR1 Breast Cancer Susceptibility Locus. PLoS Genet 6 e1001029 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001029

9. FletcherO

JohnsonN

OrrN

HoskingFJ

GibsonLJ

2011 Novel Breast Cancer Susceptibility Locus at 9q31.2: Results of a Genome-Wide Association Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 103 425 35

10. CaiQ

WenW

QuS

LiG

EganKM

2011 Replication and Functional Genomic Analyses of the Breast Cancer Susceptibility Locus at 6q25.1 Generalize Its Importance in Women of Chinese, Japanese, and European Ancestry. Cancer Res 71 1344 1355

11. FrasorJ

DanesJM

KommB

ChangKC

LyttleCR

2003 Profiling of estrogen up - and down-regulated gene expression in human breast cancer cells: insights into gene networks and pathways underlying estrogenic control of proliferation and cell phenotype. Endocrinology 144 4562 4574

12. OhDS

TroesterMA

UsaryJ

HuZ

HeX

2006 Estrogen-regulated genes predict survival in hormone receptor-positive breast cancers. J Clin Oncol 24 1656 1664

13. YuJ

YuJ

CorderoKE

JohnsonMD

GhoshD

2008 A transcriptional fingerprint of estrogen in human breast cancer predicts patient survival. Neoplasia 10 79 88

14. MillerWR

LarionovAA

RenshawL

AndersonTJ

WhiteS

2007 Changes in breast cancer transcriptional profiles after treatment with the aromatase inhibitor, letrozole. Pharmacogenet Genomics 17 813 826

15. MackayA

UrruticoecheaA

DixonJM

DexterT

FenwickK

2007 Molecular response to aromatase inhibitor treatment in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 9 R37

16. Mello-GrandM

SinghV

GhimentiC

ScatoliniM

RegoloL

2010 Gene expression profiling and prediction of response to hormonal neoadjuvant treatment with anastrozole in surgically resectable breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat

17. CarrollJS

MeyerCA

SongJ

LiW

GeistlingerTR

2006 Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genet 38 1289 1297

18. FullwoodMJ

LiuMH

PanYF

LiuJ

XuH

2009 An oestrogen-receptor-alpha-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature 462 58 64

19. RaeJM

JohnsonMD

ScheysJO

CorderoKE

LariosJM

2005 GREB 1 is a critical regulator of hormone dependent breast cancer growth. Breast Cancer Res Treat 92 141 149

20. ShangY

HuX

DiRenzoJ

LazarMA

BrownM

2000 Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell 103 843 852

21. MusgroveEA

SutherlandRL

2009 Biological determinants of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 9 631 643

22. AliS

CoombesRC

2002 Endocrine-responsive breast cancer and strategies for combating resistance. Nat Rev Cancer 2 101 112

23. SmithIE

WalshG

SkeneA

LlombartA

MayordomoJI

2007 A phase II placebo-controlled trial of neoadjuvant anastrozole alone or with gefitinib in early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25 3816 3822

24. WangY

KlijnJG

ZhangY

SieuwertsAM

LookMP

2005 Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet 365 671 679

25. HolstF

StahlPR

RuizC

HellwinkelO

JehanZ

2007 Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) gene amplification is frequent in breast cancer. Nat Genet 39 655 660

26. Reis-FilhoJS

DruryS

LambrosMB

MarchioC

JohnsonN

2008 ESR1 gene amplification in breast cancer: a common phenomenon? Nat Genet 40 809 810; author reply 810-802

27. MackayA

TamberN

FenwickK

IravaniM

GrigoriadisA

2009 A high-resolution integrated analysis of genetic and expression profiles of breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat 118 481 498

28. XiaW

BacusS

HegdeP

HusainI

StrumJ

2006 A model of acquired autoresistance to a potent ErbB2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor and a therapeutic strategy to prevent its onset in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 7795 7800

29. LearyAF

MartinL

ThornhillA

DowsettM

JohnstonS

2010 Combining or Sequencing Targeted Therapies in ER+/HER2 Amplified Breast Cancer (BC): In Vitro and In Vivo Studies of Letrozole and Lapatinib in an ER+/HER2+ Aromatase-Transfected BC Model. Cancer Res 70 292s

30. MartinLA

FarmerI

JohnstonSR

AliS

MarshallC

2003 Enhanced estrogen receptor (ER) alpha, ERBB2, and MAPK signal transduction pathways operate during the adaptation of MCF-7 cells to long term estrogen deprivation. J Biol Chem 278 30458 30468

31. WakelingAE

BowlerJ

1992 ICI 182,780, a new antioestrogen with clinical potential. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 43 173 177

32. McClellandRA

GeeJM

FrancisAB

RobertsonJF

BlameyRW

1996 Short-term effects of pure anti-oestrogen ICI 182780 treatment on oestrogen receptor, epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor-alpha protein expression in human breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 32A 413 416

33. LiGJ

ZhaoQ

ZhengW

2005 Alteration at translational but not transcriptional level of transferrin receptor expression following manganese exposure at the blood-CSF barrier in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 205 188 200

34. GhazouiZ

BuffaFM

DunbierAK

AndersonH

DexterT

2011 Close and stable relationship between proliferation and a hypoxia metagene in aromatase inhibitor treated ER-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res

35. LoiS

Haibe-KainsB

DesmedtC

WirapatiP

LallemandF

2008 Predicting prognosis using molecular profiling in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. BMC Genomics 9 239

36. LoiS

Haibe-KainsB

DesmedtC

LallemandF

TuttAM

2007 Definition of clinically distinct molecular subtypes in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinomas through genomic grade. J Clin Oncol 25 1239 1246

37. DruryS

JohnsonN

HillsM

SalterJ

DunbierA

2010 A breast cancer-associated SNP adjacent to ESR1 correlates with oestrogen receptor-alpha (ER alpha) level in invasive breast tumours. Cancer Res 69 4138

38. DunbierAK

AndersonH

GhazouiZ

PancholiS

SidhuK

2010 ESR1 is co-expressed with closely adjacent novel genes in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Presented at the 101st American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting, Washington DC, USA Abstract number 2916

39. LazennecG

HuignardH

ValotaireY

KernL

1995 Characterization of the transcription start point of the trout estrogen receptor-encoding gene: evidence for alternative splicing in the 5′ untranslated region. Gene 166 243 247

40. MartinMB

SacedaM

Garcia-MoralesP

GottardisMM

1994 Regulation of estrogen receptor expression. Breast Cancer Res Treat 31 183 189

41. MartinMB

AngeloniSV

Garcia-MoralesP

ShollerPF

Castro-GalacheMD

2004 Regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha expression in MCF-7 cells by taxol. J Endocrinol 180 487 496

42. AngeloniSV

MartinMB

Garcia-MoralesP

Castro-GalacheMD

FerragutJA

2004 Regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha expression by the tumor suppressor gene p53 in MCF-7 cells. J Endocrinol 180 497 504

43. Lieberman-AidenE

van BerkumNL

WilliamsL

ImakaevM

RagoczyT

2009 Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326 289 293

44. http://www.genecards.org/

45. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene

46. EwingRM

ChuP

ElismaF

LiH

TaylorP

2007 Large-scale mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry. Mol Syst Biol 3 89

47. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group 1998 Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 351 1451 1467

48. The World Medical Association: Declaration of Helsinki. http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3htm

49. DuP

KibbeWA

LinSM

2008 lumi: a pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics 24 1547 1548

50. KornEL

TroendleJF

McShaneLM

SimonR

2004 Controlling the number of false discoveries: application to high-dimensional genomic data. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference 124 379 398

51. MillerLD

SmedsJ

GeorgeJ

VegaVB

VergaraL

2005 An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 13550 13555

52. DesmedtC

PietteF

LoiS

WangY

LallemandF

2007 Strong time dependence of the 76-gene prognostic signature for node-negative breast cancer patients in the TRANSBIG multicenter independent validation series. Clin Cancer Res 13 3207 3214

53. HuangF

ReevesK

HanX

FairchildC

PlateroS

2007 Identification of candidate molecular markers predicting sensitivity in solid tumors to dasatinib: rationale for patient selection. Cancer Res 67 2226 2238

54. GhazouiZ

BuffaFM

DunbierAK

AndersonH

DexterT

2009 Aromatase Inhibitors Reduce the Expression of a Hypoxia Metagene in Oestrogen Receptor Positive Breast Cancer in Postmenopausal Women. Cancer Res 69 408

55. MarchioC

IravaniM

NatrajanR

LambrosMB

SavageK

2008 Genomic and immunophenotypical characterization of pure micropapillary carcinomas of the breast. J Pathol 215 398 410

56. NatrajanR

WeigeltB

MackayA

GeyerFC

GrigoriadisA

2010 An integrative genomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals molecular pathways and networks regulated by copy number aberrations in basal-like, HER2 and luminal cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 121 575 589

57. DruryS

AndersonH

DowsettM

2009 Selection of REFERENCE genes for normalization of qRT-PCR data derived from FFPE breast tumors. Diagn Mol Pathol 18 103 107

58. PancholiS

LykkesfeldtAE

HilmiC

BanerjeeS

LearyA

2008 ERBB2 influences the subcellular localization of the estrogen receptor in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 cells leading to the activation of AKT and RPS6KA2. Endocr Relat Cancer 15 985 1002

59. DarbreP

YatesJ

CurtisS

KingRJ

1983 Effect of estradiol on human breast cancer cells in culture. Cancer Res 43 349 354

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Incorporating Biological Pathways via a Markov Random Field Model in Genome-Wide Association StudiesČlánek Survival Motor Neuron Protein Regulates Stem Cell Division, Proliferation, and Differentiation inČlánek Epigenetic Regulation of Cell Type–Specific Expression Patterns in the Human Mammary Epithelium

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 4

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Is Co-Expressed with Closely Adjacent Uncharacterised Genes Spanning a Breast Cancer Susceptibility Locus at 6q25.1

- The Liberation of Embryonic Stem Cells

- Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies Regions on 7p21 () and 15q24 () As Determinants of Habitual Caffeine Consumption

- A Sustained Dietary Change Increases Epigenetic Variation in Isogenic Mice

- The Exocyst Protein Sec10 Interacts with Polycystin-2 and Knockdown Causes PKD-Phenotypes

- Incorporating Biological Pathways via a Markov Random Field Model in Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Survival Motor Neuron Protein Regulates Stem Cell Division, Proliferation, and Differentiation in

- Identification and Functional Validation of the Novel Antimalarial Resistance Locus in

- Does Positive Selection Drive Transcription Factor Binding Site Turnover? A Test with Drosophila Cis-Regulatory Modules

- Protein Phosphatase 2A Controls Ethylene Biosynthesis by Differentially Regulating the Turnover of ACC Synthase Isoforms

- Ribosomal DNA Deletions Modulate Genome-Wide Gene Expression: “–Sensitive” Genes and Natural Variation

- Reciprocal Sign Epistasis between Frequently Experimentally Evolved Adaptive Mutations Causes a Rugged Fitness Landscape

- Variable Pathogenicity Determines Individual Lifespan in

- Evolution of Vertebrate Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 3 Channels: Opposite Temperature Sensitivity between Mammals and Western Clawed Frogs

- Towards Establishment of a Rice Stress Response Interactome

- Mouse Genome-Wide Association and Systems Genetics Identify As a Regulator of Bone Mineral Density and Osteoclastogenesis

- Quantitative Fitness Analysis Shows That NMD Proteins and Many Other Protein Complexes Suppress or Enhance Distinct Telomere Cap Defects

- Highly Precise and Developmentally Programmed Genome Assembly in Requires Ligase IV–Dependent End Joining

- PDP-1 Links the TGF-β and IIS Pathways to Regulate Longevity, Development, and Metabolism

- Genome-Wide Association Study Using Extreme Truncate Selection Identifies Novel Genes Affecting Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk

- Eight Common Genetic Variants Associated with Serum DHEAS Levels Suggest a Key Role in Ageing Mechanisms

- 14-3-3 Proteins Regulate Exonuclease 1–Dependent Processing of Stalled Replication Forks

- HDA6 Regulates Locus-Directed Heterochromatin Silencing in Cooperation with MET1

- Epigenetic Regulation of Cell Type–Specific Expression Patterns in the Human Mammary Epithelium

- Enhanced Statistical Tests for GWAS in Admixed Populations: Assessment using African Americans from CARe and a Breast Cancer Consortium

- Beyond Missing Heritability: Prediction of Complex Traits

- An Evolutionary Genomic Approach to Identify Genes Involved in Human Birth Timing

- Long-Lost Relative Claims Orphan Gene: in a Wasp

- PTG Depletion Removes Lafora Bodies and Rescues the Fatal Epilepsy of Lafora Disease

- Chromatin Organization in Sperm May Be the Major Functional Consequence of Base Composition Variation in the Human Genome

- GWAS of Follicular Lymphoma Reveals Allelic Heterogeneity at 6p21.32 and Suggests Shared Genetic Susceptibility with Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma

- Loss-of-Function Mutations in Cause Metachondromatosis, but Not Ollier Disease or Maffucci Syndrome

- DNA Damage, Somatic Aneuploidy, and Malignant Sarcoma Susceptibility in Muscular Dystrophies

- The Phylogenetic Origin of Coincided with the Origin of Maternally Provisioned Germ Plasm and Pole Cells at the Base of the Holometabola

- Genome Analysis Reveals Interplay between 5′UTR Introns and Nuclear mRNA Export for Secretory and Mitochondrial Genes

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Soluble ICAM-1 Concentration Reveals Novel Associations at the , , , and Loci

- The Complete Spectrum of Yeast Chromosome Instability Genes Identifies Candidate CIN Cancer Genes and Functional Roles for ASTRA Complex Components

- Dynamic Regulation of H3K27 Trimethylation during Differentiation

- Phosphorylation-Dependent Differential Regulation of Plant Growth, Cell Death, and Innate Immunity by the Regulatory Receptor-Like Kinase BAK1

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- PTG Depletion Removes Lafora Bodies and Rescues the Fatal Epilepsy of Lafora Disease

- Evolution of Vertebrate Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 3 Channels: Opposite Temperature Sensitivity between Mammals and Western Clawed Frogs

- Survival Motor Neuron Protein Regulates Stem Cell Division, Proliferation, and Differentiation in

- An Evolutionary Genomic Approach to Identify Genes Involved in Human Birth Timing

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání