-

Články

Reklama

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

ReklamaYeast Prions: Proteins Templating Conformation and an Anti-prion System

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004584

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004584Summary

article has not abstract

Introduction

Most yeast prions (infectious proteins) are amyloids, linear β-sheet-rich polymers of a single protein with the β-strands perpendicular to the long axis of the filament. A single prion protein can form any of many different prion variants, differing in structure and biological properties, but with the same amino acid sequence. The folded in-register parallel β-sheet architecture we have shown for several yeast prions explains how a given prion variant can be propagated stably, how a protein can template its conformation, just as DNA can template its sequence. We have found an anti-prion system that sequesters prion seeds, preventing their even distribution to daughter cells. This system involves Btn2p, Cur1p, and Hsp42, and cures most of the [URE3] variants arising. Btn2p is weakly homologous to mammalian HOOK proteins, which include the aggresome-active HOOK2.

While mammalian prions (infectious proteins) are rare, many common human amyloid diseases, such as Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and others, have prion aspects, including infectivity in some cases. Most yeast prions are infectious amyloids, filamentous polymers of a single protein. Work on yeast prions was the first to establish the protein-only (prion) hypothesis, and, now, work on the structure of yeast prion infectious amyloid explains how a prion protein can template its conformation, just as DNA can template its sequence. The recent discovery of a cellular anti-prion system that cures most arising prions of the yeast Ure2 protein offers a possible direction to look for treatments of amyloidoses.

The yeast non-chromosomal genetic elements [URE3] and [PSI+] were discovered to be prions of Ure2p and Sup35p, respectively, based on their unusual genetic properties [1], and were demonstrated to be based on amyloids of these proteins [2–4]. There are now at least eight amyloid-based prions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (reviewed in [5,6]) and one of Podospora anserina [7]. In addition to the PrP-related mammalian prion diseases, recent work indicates that Alzheimer disease and other common human amyloidoses have prion-like aspects, including infectivity (reviewed by [8]). This broadens the importance of detailed studies of yeast prions.

Prion Variants

[PSI+] and [URE3] show a remarkably wide array of variants: strong and several degrees of weak variants differ in the intensity of the prion phenotype; stable and unstable (each of which can be strong or weak); transmissible (or not) to a given sequence polymorph of the prion protein (each of which can be strong or weak); curable (or not) by overproduction or deficiency of various chaperones; and lethal, toxic, or mild in its detrimental effects on cells [9–11].

Biology of Yeast Prions

Mammalian prions are uniformly fatal, and common variants of [PSI+] and [URE3] are lethal or nearly so [11], but other, quite mild variants of the same prions are most often studied. [PSI+] and [URE3] are rare in wild strains [12,13] showing that even the mildest variants are a net detriment to their hosts. Whether even the mildest [PSI+] or [URE3] confer any benefit in any strain is controversial, but the [HET-s] prion of P. anserina is beneficial to its host (reviewed by Saupe [7]). The ability of Ure2p and Sup35p to form the prions [URE3] and [PSI+] is not conserved but is found sporadically distributed among the species examined so far (e.g., [14]).

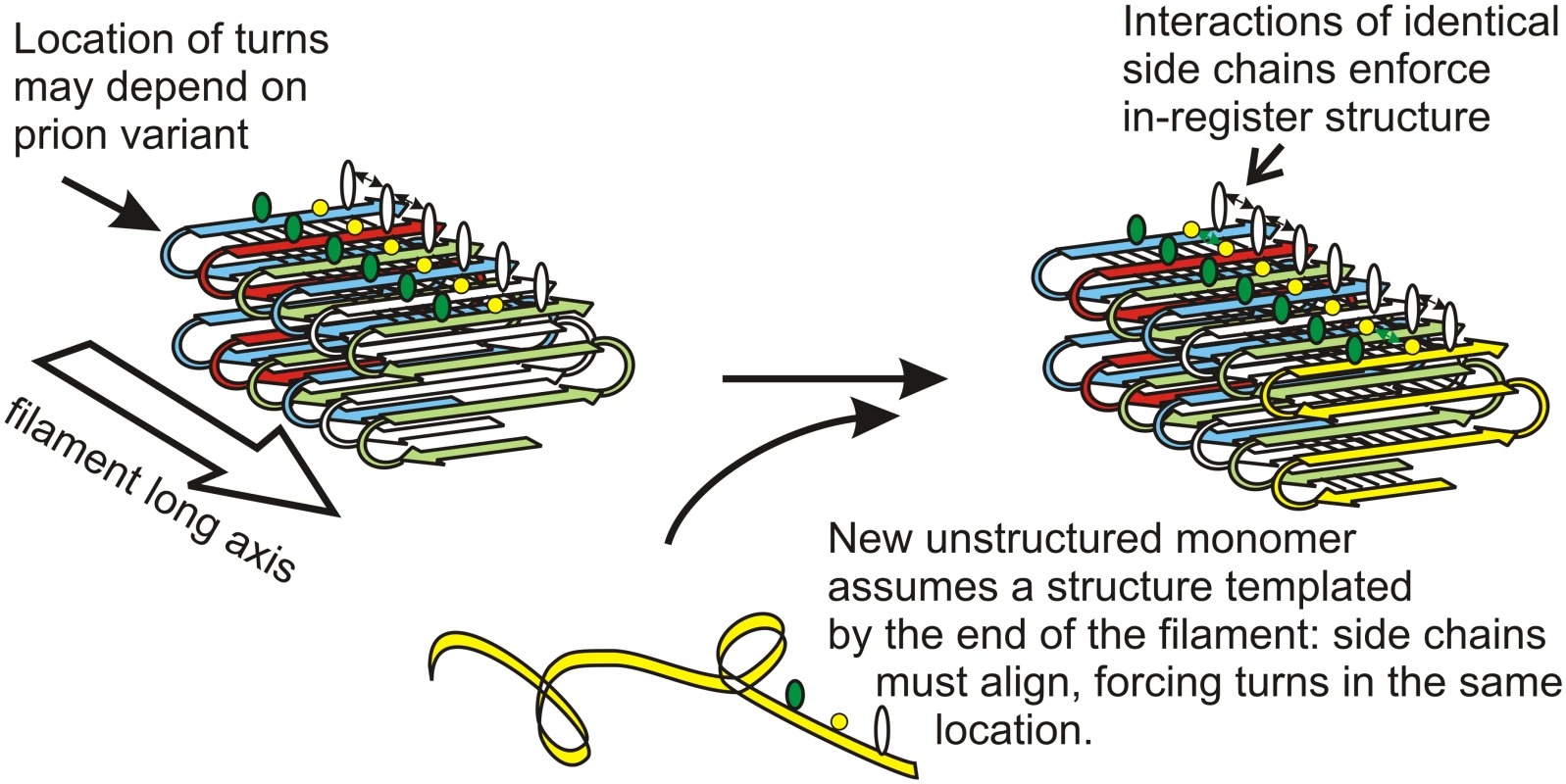

Structure Explains Inheritance

Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements and filament mass per length determinations show that amyloid filaments of the prion domains (the amyloid-forming parts) of the yeast prion proteins Sup35p, Ure2p, and Rnq1p have a folded, in-register, parallel β-sheet architecture (Fig. 1) (e.g., [15,16]). For Sup35p, we have evidence for the location of some folds [16]. This means that for each residue, there is a line of identical side chains along the long axis of the fiber. Positive interactions among these side chains (hydrophobic interactions for LVIYFWM or hydrogen bonding for QNST; there are very few charged residues) can only happen if the structure is in-register, and so serve to keep it in-register. Filament elongation occurs by addition of monomers [17], and the same positive interactions force a new monomer joining the end of the filament to align with monomers already in the filament, and so have its turns (locations of the folds in the sheet) in the same locations, and the same extent of β-sheet (Fig. 1) [6,18]. In this way, the protein molecules template their conformation and impose it on monomers joining the ends of the filament, just as DNA templates its sequence [6,18].

Fig. 1. Protein conformation templating mechanism.

The in-register parallel amyloid architecture naturally suggests a mechanism for transfer of conformation information from molecules in the filament to those joining the filament. H-bonding or hydrophobic favorable interactions among identical side chains require in-register alignment for the interactions. This directs the monomer joining the end of the filament to have its folds/turns at the same residues as previous molecules in the filament. Different prion variants have folds/turns at different locations, but each is faithfully propagated by this mechanism. Modified from [6]. The Anti-prion Proteins Btn2 and Cur1

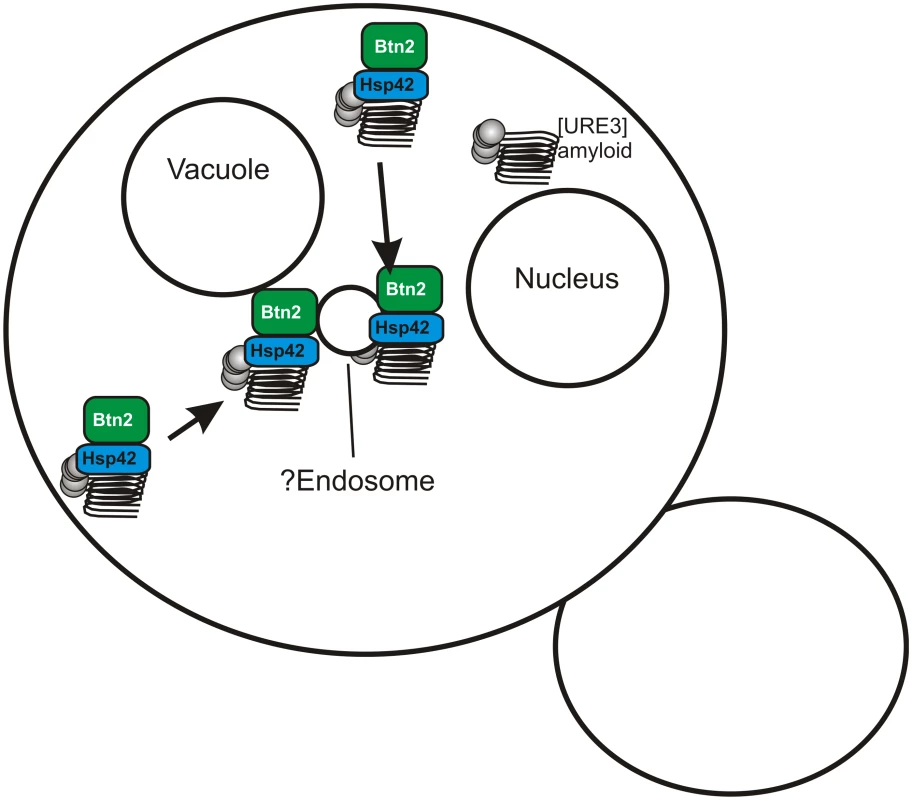

A search for yeast proteins whose overproduction cures the [URE3–1] prion produced two paralogs, Btn2p and Cur1p [19]. Early in the process of curing of [URE3–1] by overproduction of Btn2p, the aggregates of Ure2p, normally scattered in the cytoplasm in [URE3] strains [20], were concentrated at a single locus in the cell, coincident with Btn2p, also in a single site in the cell [19]. This suggests that the overproduced Btn2p sequesters prion aggregates at one site in the cell so that on division, only one of the two daughter cells gets aggregates and the other is cured. In a double mutant btn2Δ cur1Δ strain, the number of infectious aggregates (“seeds”) is significantly greater than in an isogenic wild-type cell suggesting that Btn2p and Cur1p are sequestering aggregates even at their normal levels [19].

Recently, we generated an array of [URE3]s in a btn2Δ cur1Δ strain, and found that nearly all such prion isolates were cured by restoration of just the normal levels of either Btn2p or Cur1p (although curing was most efficient if both were restored) [21]. Direct measurements showed that prion variants cured by normal levels of Btn2p or Cur1p had seed numbers several fold lower than variants that were only cured by overproduction of one or the other of these proteins [21]. These “Btn2-Cur1-hypersensitive” variants ([URE3-bcs]) were somewhat unstable and often converted to variants only cured by overproduction of Btn2p or Cur1p. Such less sensitive prion “mutants” had a much higher seed number than their parent. These results support our prion sequestration model of curing: low seed number variants can be well-sequestered by normal levels of Btn2, while higher seed number variants need overproduced Btn2 to be cured (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Btn2p sequesters prion amyloid filaments, curing the prion.

Btn2p gathers filaments of Ure2p amyloid (the [URE3] prion) to a single site in the cell, possibly the endosome. If the prion has a low seed number then even the normal levels of Btn2p are sufficient to sequester nearly all of the seeds, so that daughter cells without seeds, and therefore cured of the prion, are often produced. Yeast have an array of methods of dealing with protein aggregates, whether amyloid or non-amyloid, including degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, the autophagy system, aggresomes in mammalian cells, chaperones to resolubilize, and others. Inducing autophagy does not cure [URE3], nor does blocking autophagy prevent overproduced Btn2 or Cur1 from curing [URE3] [19]. Bmh1p is necessary for the collection of polyQ aggregates at a special site in yeast, possibly comparable to the aggresome [22], but bmh1Δ does not interfere with curing of [URE3] by overproduced Btn2 or Cur1 [21]. The E3 ubiquitin ligases San1p and Ubr1p responsible for marking cytoplasmic proteins for degradation in nuclear proteasomes [23] are not needed for [URE3] curing by overproduced Btn2 or Cur1 [21].

Hsp42, a small heat shock protein, was found to bring several non-amyloid aggregates to a site peripheral to the nucleus, and to be necessary for their collection at that site [24]. Hsp42 interacts with Btn2 and these two proteins colocalize with each other and non-amyloid aggregated proteins [25,26]. We found that Hsp42 is needed for curing of [URE3] by overproduction of Btn2p, and overproduction of Hsp42 itself cures [URE3]. Hsp42 curing of [URE3] requires Cur1p [21]. Evidently Btn2p, Cur1p, and Hsp42 work together in this prion-curing process, apparently by sequestering prion aggregates.

The Btn2/Cur1 system(s) selects the small minority of [URE3] variants that are not cured by normal levels of these proteins and, accordingly, the frequency of spontaneous [URE3] is five-fold higher in a btn2Δ cur1Δ strain than in wild type [21]. Thus, cells are quite effective in eliminating this prion, suggesting that the cells do not consider having this prion to be a “good thing.”

Conclusions

Remarkably, a single protein sequence can be the basis of many different protein variants, based on different (but as yet not precisely defined) conformations of the protein in the amyloid (e.g., [3,27]). The folded parallel in-register β-sheet architecture of yeast prion amyloids naturally suggests a templating mechanism that explains this remarkable fact [18]. Just as DNA can be a gene by templating its sequence, proteins can be genes by templating their conformation.

While an array of methods have been found to cure yeast prions by over - or underproduction of various chaperones and other proteins and by various conditions (reviewed in [28]), Btn2 and Cur1 cure the [URE3] prion at normal expression levels, indicating that this is a cellular anti-prion system. The homology of Btn2p to human HOOK proteins, a family that includes the aggresome-promoting protein HOOK2, suggests that information gleaned from the yeast systems will have application in efforts to control human prions and amyloidoses.

Zdroje

1. Wickner RB (1994) [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in S. cerevisiae. Science 264 : 566–569. 7909170

2. King CY, Diaz-Avalos R (2004) Protein-only transmission of three yeast prion strains. Nature 428 : 319–323. 15029195

3. Tanaka M, Chien P, Naber N, Cooke R, Weissman JS (2004) Conformational variations in an infectious protein determine prion strain differences. Nature 428 : 323–328. 15029196

4. Brachmann A, Baxa U, Wickner RB (2005) Prion generation in vitro: amyloid of Ure2p is infectious. Embo J 24 : 3082–3092. 16096644

5. Liebman SW, Chernoff YO (2012) Prions in yeast. Genetics 191 : 1041–1072. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137760 22879407

6. Wickner RB, Edskes HK, Bateman DA, Kelly AC, Gorkovskiy A, et al. (2013) Amyloids and yeast prion biology. Biochemistry 52 : 1514–1527. doi: 10.1021/bi301686a 23379365

7. Saupe SJ (2011) The [Het-s] prion of Podospora anserina and its role in heterokaryon incompatibility. Sem Cell & Dev Biol 22 : 460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.02.019 21334447

8. Kraus A, Groveman BR, Caughey B (2013) Prions and the potential transmissibility of protein misfolding diseases. Ann Rev Microbiol 67 : 543–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155735 23808331

9. Derkatch IL, Chernoff YO, Kushnirov VV, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW (1996) Genesis and variability of [PSI] prion factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 144 : 1375–1386. 8978027

10. King CY (2001) Supporting the structural basis of prion strains: induction and identification of [PSI] variants. J Mol Biol 307 : 1247–1260. 11292339

11. McGlinchey R, Kryndushkin D, Wickner RB (2011) Suicidal [PSI+] is a lethal yeast prion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108 : 5337–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102762108 21402947

12. Nakayashiki T, Kurtzman CP, Edskes HK, Wickner RB (2005) Yeast prions [URE3] and [PSI+] are diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 10575–10580. 16024723

13. Halfmann R, Jarosz DF, Jones SK, Chang A, Lancster AK, et al. (2012) Prions are a common mechanism for phenotypic inheritance in wild yeasts. Nature 482 : 363–368. doi: 10.1038/nature10875 22337056

14. Edskes HE, Khamar HJ, Winchester C-L, Greenler AJ, Zhou A, et al. (2014) Sporadic distribution of prion-forming ability of Sup35p from yeasts and fungi. Genetics epub ahead of print.

15. Shewmaker F, Wickner RB, Tycko R (2006) Amyloid of the prion domain of Sup35p has an in-register parallel β-sheet structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103 : 19754–19759. 17170131

16. Gorkovskiy A, Thurber KR, Tycko R, Wickner RB (2014) Locating the folds of the in-register parallel β-sheet of the Sup35p prion domain infectious amyloid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: in press. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421566112 25552562

17. Collins SR, Douglass A, Vale RD, Weissman JS (2004) Mechanism of prion propagation: amyloid growth occurs by monomer addition. Plos Biol 2 : 1582–1590.

18. Wickner RB, Edskes HK, Shewmaker F, Nakayashiki T (2007) Prions of fungi: inherited structures and biological roles. Nat Rev Microbiol 5 : 611–618. 17632572

19. Kryndushkin D, Shewmaker F, Wickner RB (2008) Curing of the [URE3] prion by Btn2p, a Batten disease-related protein. EMBO J 27 : 2725–2735. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.198 18833194

20. Edskes HK, Gray VT, Wickner RB (1999) The [URE3] prion is an aggregated form of Ure2p that can be cured by overexpression of Ure2p fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 : 1498–1503. 9990052

21. Wickner RB, Beszonov E, Bateman DA (2014) Normal levels of the antiprion proteins Btn2 and Cur1 cure most newly formed [URE3] prion variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421566112 25552562

22. Wang Y, Meriin AB, Zaarur N, Romanova NV, Chernoff YO, et al. (2009) Abnormal proteins can form aggresome in yeast: aggresome-targeting signals and components of the machinery. FASEB J 23 : 451–463. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-117614 18854435

23. Gardner RG, Nelson ZW, Gottschling DE (2005) Degradation-mediated protein quality control in the nucleus. Cell 120 : 803–815. 15797381

24. Specht S, Miller SBM, Mogk A, Bukau B (2011) Hsp42 is required for sequestration of protein aggregates into deposition sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 195 : 617–629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106037 22065637

25. Malinovska L, Kroschwald S, Munder MC, Richter D, Alberti S (2012) Molecular chaperones and stress-inducible protein-sorting factors coordinate the spaciotemporal distribution of protein aggregates. Mol Biol Cell 23 : 3041–3056. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-03-0194 22718905

26. Kryndushkin D, Ihrke G, Piermartiri TC, Shewmaker F (2012) A yeast model of optineurin proteinopathy reveals a unique aggregation pattern associated with cellular toxicity. Mol Microbiol Epub ahead of print.

27. Bessen RA, Marsh RF (1992) Biochemical and physical properties of the prion protein from two strains of the transmissible mink encephalopathy agent. J Virol 66 : 2096–2101. 1347795

28. Liebman SW, Chernoff YO (2012) Prions in yeast. Genetics 191 : 1041–1072. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137760 22879407

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek 2014 Reviewer Thank YouČlánek Characterization of Metabolically Quiescent Parasites in Murine Lesions Using Heavy Water LabelingČlánek High Heritability Is Compatible with the Broad Distribution of Set Point Viral Load in HIV Carriers

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 2- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- 2014 Reviewer Thank You

- A Case for Two-Component Signaling Systems As Antifungal Drug Targets

- Prions—Not Your Immunologist’s Pathogen

- Telomeric ORFS in : Does Mediator Tail Wag the Yeast?

- Livestock-Associated : The United States Experience

- The Neurotrophic Receptor Ntrk2 Directs Lymphoid Tissue Neovascularization during Infection

- The Intracellular Bacterium Uses Parasitoid Wasps as Phoretic Vectors for Efficient Horizontal Transmission

- CD200 Receptor Restriction of Myeloid Cell Responses Antagonizes Antiviral Immunity and Facilitates Cytomegalovirus Persistence within Mucosal Tissue

- Phage-mediated Dispersal of Biofilm and Distribution of Bacterial Virulence Genes Is Induced by Quorum Sensing

- CXCL9 Contributes to Antimicrobial Protection of the Gut during Infection Independent of Chemokine-Receptor Signaling

- Mitigation of Prion Infectivity and Conversion Capacity by a Simulated Natural Process—Repeated Cycles of Drying and Wetting

- Approaches Reveal a Key Role for DCs in CD4+ T Cell Activation and Parasite Clearance during the Acute Phase of Experimental Blood-Stage Malaria

- Revealing the Sequence and Resulting Cellular Morphology of Receptor-Ligand Interactions during Invasion of Erythrocytes

- Crystal Structures of the Carboxyl cGMP Binding Domain of the cGMP-dependent Protein Kinase Reveal a Novel Capping Triad Crucial for Merozoite Egress

- Non-redundant and Redundant Roles of Cytomegalovirus gH/gL Complexes in Host Organ Entry and Intra-tissue Spread

- Characterization of Metabolically Quiescent Parasites in Murine Lesions Using Heavy Water Labeling

- A Working Model of How Noroviruses Infect the Intestine

- CD44 Plays a Functional Role in -induced Epithelial Cell Proliferation

- Novel Inhibitors of Cholesterol Degradation in Reveal How the Bacterium’s Metabolism Is Constrained by the Intracellular Environment

- G-Quadruplexes in Pathogens: A Common Route to Virulence Control?

- A Rho GDP Dissociation Inhibitor Produced by Apoptotic T-Cells Inhibits Growth of

- Manipulating Adenovirus Hexon Hypervariable Loops Dictates Immune Neutralisation and Coagulation Factor X-dependent Cell Interaction and

- The RhoGAP SPIN6 Associates with SPL11 and OsRac1 and Negatively Regulates Programmed Cell Death and Innate Immunity in Rice

- Lymph-Node Resident CD8α Dendritic Cells Capture Antigens from Migratory Malaria Sporozoites and Induce CD8 T Cell Responses

- Coordinated Function of Cellular DEAD-Box Helicases in Suppression of Viral RNA Recombination and Maintenance of Viral Genome Integrity

- IL-33-Mediated Protection against Experimental Cerebral Malaria Is Linked to Induction of Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells, M2 Macrophages and Regulatory T Cells

- Evasion of Autophagy and Intracellular Killing by Human Myeloid Dendritic Cells Involves DC-SIGN-TLR2 Crosstalk

- CD8 T Cell Response Maturation Defined by Anentropic Specificity and Repertoire Depth Correlates with SIVΔnef-induced Protection

- Diverse Heterologous Primary Infections Radically Alter Immunodominance Hierarchies and Clinical Outcomes Following H7N9 Influenza Challenge in Mice

- Human Adenovirus 52 Uses Sialic Acid-containing Glycoproteins and the Coxsackie and Adenovirus Receptor for Binding to Target Cells

- Super-Resolution Imaging of ESCRT-Proteins at HIV-1 Assembly Sites

- Disruption of an Membrane Protein Causes a Magnesium-dependent Cell Division Defect and Failure to Persist in Mice

- Recognition of Hyphae by Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Is Mediated by Dectin-2 and Results in Formation of Extracellular Traps

- Essential Domains of Invasins Utilized to Infect Mammalian Host Cells

- High Heritability Is Compatible with the Broad Distribution of Set Point Viral Load in HIV Carriers

- Yeast Prions: Proteins Templating Conformation and an Anti-prion System

- A Novel Mechanism of Bacterial Toxin Transfer within Host Blood Cell-Derived Microvesicles

- A Wild Strain Has Enhanced Epithelial Immunity to a Natural Microsporidian Parasite

- Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection by γδ T Cells

- Dimorphism in Fungal Pathogens of Mammals, Plants, and Insects

- Recognition and Activation Domains Contribute to Allele-Specific Responses of an Arabidopsis NLR Receptor to an Oomycete Effector Protein

- Direct Binding of Retromer to Human Papillomavirus Type 16 Minor Capsid Protein L2 Mediates Endosome Exit during Viral Infection

- Characterization of the Mycobacterial Acyl-CoA Carboxylase Holo Complexes Reveals Their Functional Expansion into Amino Acid Catabolism

- Prion Infections and Anti-PrP Antibodies Trigger Converging Neurotoxic Pathways

- Evolution of Genome Size and Complexity in the

- Antibiotic Modulation of Capsular Exopolysaccharide and Virulence in

- IFNγ Signaling Endows DCs with the Capacity to Control Type I Inflammation during Parasitic Infection through Promoting T-bet+ Regulatory T Cells

- Identification of Effective Subdominant Anti-HIV-1 CD8+ T Cells Within Entire Post-infection and Post-vaccination Immune Responses

- Viral and Cellular Proteins Containing FGDF Motifs Bind G3BP to Block Stress Granule Formation

- ATPaseTb2, a Unique Membrane-bound FoF1-ATPase Component, Is Essential in Bloodstream and Dyskinetoplastic Trypanosomes

- Cytoplasmic Actin Is an Extracellular Insect Immune Factor which Is Secreted upon Immune Challenge and Mediates Phagocytosis and Direct Killing of Bacteria, and Is a Antagonist

- A Specific A/T Polymorphism in Western Tyrosine Phosphorylation B-Motifs Regulates CagA Epithelial Cell Interactions

- Within-host Competition Does Not Select for Virulence in Malaria Parasites; Studies with

- A Membrane-bound eIF2 Alpha Kinase Located in Endosomes Is Regulated by Heme and Controls Differentiation and ROS Levels in

- Cytosolic Access of : Critical Impact of Phagosomal Acidification Control and Demonstration of Occurrence

- Role of Pentraxin 3 in Shaping Arthritogenic Alphaviral Disease: From Enhanced Viral Replication to Immunomodulation

- Rational Development of an Attenuated Recombinant Cyprinid Herpesvirus 3 Vaccine Using Prokaryotic Mutagenesis and In Vivo Bioluminescent Imaging

- HITS-CLIP Analysis Uncovers a Link between the Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus ORF57 Protein and Host Pre-mRNA Metabolism

- Molecular and Functional Analyses of a Maize Autoactive NB-LRR Protein Identify Precise Structural Requirements for Activity

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection by γδ T Cells

- ATPaseTb2, a Unique Membrane-bound FoF1-ATPase Component, Is Essential in Bloodstream and Dyskinetoplastic Trypanosomes

- Rational Development of an Attenuated Recombinant Cyprinid Herpesvirus 3 Vaccine Using Prokaryotic Mutagenesis and In Vivo Bioluminescent Imaging

- Telomeric ORFS in : Does Mediator Tail Wag the Yeast?

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání