-

Články

Reklama

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

ReklamaThe NLRP3 Inflammasome Is a Pathogen Sensor for Invasive via Activation of α5β1 Integrin at the Macrophage-Amebae Intercellular Junction

Amebiasis caused by the enteric protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica is among the three top causes of death from parasitic infections worldwide, as a result of amebic colitis (dysentery) and liver or brain abscess. When Eh invades the intestinal barrier and contacts host tissue there is a profound inflammatory response, which is thought to drive the disease. One of the central outstanding questions has been how the immune response is escalated at sites of invasion. Adherence of the parasite to host cells has long been appreciated in the pathogenesis of amebiasis, but was never considered as a “cue” that host cells use to detect Eh and initiate host defense. Here we introduce the idea, and demonstrate, that an intercellular junction forms between Eh and host cells upon contact that engages the NLRP3 inflammasome. The NLRP3 inflammasome belongs to a group of “danger” sensors that are uniquely designed to rapidly activate highly inflammatory host defenses. In this work, we identified a surface receptor on macrophages that normally functions in adhesion and polarization recognizes a protein on the outer surface of Eh. Intriguingly, Eh also secretes this protein. However, the full activation of the surface receptor leading to inflammasome activation only occurs when the Eh protein is immobilized on the parasite surface. Thus, we uncovered a molecular mechanism though which host cells distinguish direct contact, and therefore recognize parasites that are immediately present in the tissue, to mobilize a highly inflammatory response. We believe this concept is central to understanding the biology of amebiasis.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004887

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004887Summary

Amebiasis caused by the enteric protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica is among the three top causes of death from parasitic infections worldwide, as a result of amebic colitis (dysentery) and liver or brain abscess. When Eh invades the intestinal barrier and contacts host tissue there is a profound inflammatory response, which is thought to drive the disease. One of the central outstanding questions has been how the immune response is escalated at sites of invasion. Adherence of the parasite to host cells has long been appreciated in the pathogenesis of amebiasis, but was never considered as a “cue” that host cells use to detect Eh and initiate host defense. Here we introduce the idea, and demonstrate, that an intercellular junction forms between Eh and host cells upon contact that engages the NLRP3 inflammasome. The NLRP3 inflammasome belongs to a group of “danger” sensors that are uniquely designed to rapidly activate highly inflammatory host defenses. In this work, we identified a surface receptor on macrophages that normally functions in adhesion and polarization recognizes a protein on the outer surface of Eh. Intriguingly, Eh also secretes this protein. However, the full activation of the surface receptor leading to inflammasome activation only occurs when the Eh protein is immobilized on the parasite surface. Thus, we uncovered a molecular mechanism though which host cells distinguish direct contact, and therefore recognize parasites that are immediately present in the tissue, to mobilize a highly inflammatory response. We believe this concept is central to understanding the biology of amebiasis.

Introduction

Entamoeba histolytica, the etiologic agent of amebiasis, is a protozoan parasite of the human colon that colonizes about 10% of the world’s population resulting in 106 deaths/year and is endemic in areas that lack adequate water sanitation [1]. Infection is acquired by ingesting cysts that release trophozoites that feed and replicate in the colon [2]. The majority of infections remain in the lumen and are tolerated without disease. For unknown reasons Eh occasionally breaches innate mucosal barriers and invades the lamina propria and submucosa where the parasite can further disseminate through the portal circulation and infect the liver. When Eh invades, there is a florid inflammatory response, components of which are thought to exacerbate the disease [2]. Currently, we lack an understanding of normal immune mechanisms that trigger this inflammatory response.

One of the central outstanding questions has been how the immune response is escalated at sites of invasion. In this regard, adherence of the parasite to host cells has long been appreciated in the pathogenesis of amebiasis, but has been overlooked as an event that itself initiates host defense and inflammation [3, 4]. During a microbial encounter the innate immune system uses a variety of cues to distinguish both the organism and the level of danger that that organism presents in order to respond appropriately so that robust host defenses that cause significant bystander damage are only triggered when pathogenic threats are severe. In this manner, a direct interaction between host cells and Eh should signify the presence of an immediate infection. In turn, the immune response should be rapidly scaled-up precisely at locations where active infections are detected to eliminate and prevent further spread of the parasite. Therefore, how the innate immune system directly recognizes Eh and how this scenario initiates and shapes host defense is critical to understand the basis of the host response and the pathogenesis of amebiasis. To address this issue, it needs to be appreciated that Eh are large, between 20–60 μM in diameter and are too big to be phagocytosed by innate immune cells. As Eh remain extracellular throughout infection, host cells acquire information about the immediate presence of Eh at points of membrane contact with trophozoites. We think this interaction is critical in understanding the pathogenesis of amebiasis.

Macrophages are thought to be crucial in the innate immune response to invasive Eh by killing the parasite directly and by driving an inflammatory response that recruits additional immune cell help to combat the infection [5, 6]. High mobility and the ability to form dynamic intercellular contacts are central to the macrophage immune-surveillance system enabling them to survey their environment for microorganisms [7]. From the onset of contact macrophages gather information about the nature of a target by exploring it’s surface by engagement of surface receptors and interactions with the plasma membrane. This leads to the recruitment and clustering of receptors at points of contact to specific molecules on the target surface, and selective activation of signaling pathways. We recently identified that direct Eh contact with macrophages induces inflammasome activation, though we did not identify the type of inflammasome involved [8]. Inflammasomes are a group of intracellular multi-protein complexes that link specific pro-inflammatory stimuli to the activation of caspase-1 [9]. Active caspase-1 in turn initiates highly potent inflammatory responses by cleaving the intracellular pro-forms of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 into their active forms and mediates their release, along with a number of other pro-inflammatory mediators, by a secretion event that remains to be defined. We determined that the major Eh surface adhesin, the Gal-lectin, provides an “adhesive” signal that enables intercellular contacts with macrophages to form, which was critical for activating the inflammasome [8]. Thus, if we blocked Eh-Gal-lectin with monoclonal antibodies that specifically target regions involved in adhesion, or if we added D-galactose to disrupt binding to galactose moieties on unknown macrophage receptors, or if we added soluble Eh-Gal-lectin to competitively inhibit Eh adherence, inflammasome activation as well as intercellular contacts were abolished [8]. The surface receptors on macrophages that ligate Eh-Gal-lectin are currently unknown and remain an area of interest. However, in the present study we explored the possibility that contact provides a platform through which other Eh surface molecules interact to coordinate inflammasome activation. Here we show that an Eh cysteine protease, termed EhCP5 that like Eh-Gal-lectin is expressed on the trophozoite surface and is secreted, is necessary for contact-dependent inflammasome activation.

We found that α5β1 integrin, a surface receptor critically involved in cell adhesion, polarization and migration is recruited into sites of contact and is highly activated by surface-bound EhCP5 through its integrin-binding RGD sequence and proteolytic activity. When soluble EhCP5 was presented to macrophages it ligated α5β1 integrin but did not enhance activation. However, when an intercellular junction was formed, EhCP5 on the trophozoite surface stimulated rapid and robust activation of α5β1 integrin. This event triggered macrophages to produce an extracellular burst of ATP through opening surface pannexin-1 (Panx1) channels that were activated by α5β1 integrin signaling. Subsequently, ATP delivered a critical stimulus to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Thus, direct sensing of Eh occurs by engagement of α5β1 integrin at the intercellular junction where NLRP3 functions as a pathogenicity sensor for invasive Eh.

Results

NLRP3 recruitment into contact sites with E. histolytica is required to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome

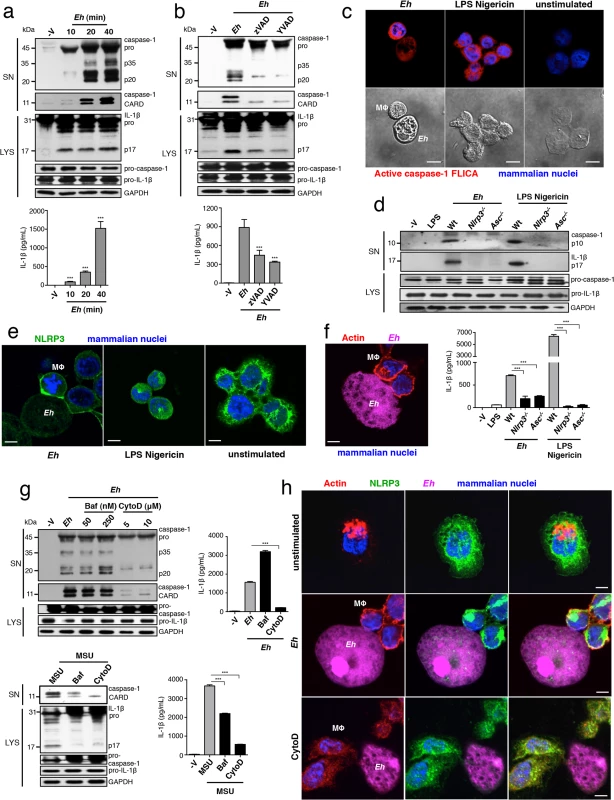

In unstimulated macrophages, caspase-1 exists as a partially active pro-enzyme of 45–55 kDa, and after recruitment to an active inflammasome platform undergoes sequential autoproteolysis to become fully active, and is secreted from the cell. Eh placed in direct contact with macrophages rapidly induced caspase-1 and IL-1β activation, as caspase-1 and IL-1β began to appear in the culture media within 10 min (Fig 1A–1C). Note that the cleavage patterns of caspase-1 result from different steps of caspase-1 processing and differences in where pro-caspase-1 and fully active caspase-1 cleave caspase-1 molecules [10]. The pro-enzyme is first cleaved into the C-terminal p10 subunit and a more active p35 fragment composed of the p20 subunit and the N-terminal CARD [10]. Cleavage of the p35 fragment separates the CARD and p20 subunit, and the p10 and p20 subunits form a fully active heterodimer [10]. We used two different human caspase-1 antibodies to assess caspase-1 activation in response to Eh: one that detects the p20, p35 and pro-caspase-1 (top immunoblot) and another that detects the cleaved CARD domain (bottom immunoblot).

Fig. 1. E. histolytica activates the NLRP3 inflammasome upon contact.

PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages (a-c, e-h) and BMDM (d) treated for 30 min or the indicated time with live Eh at a 1:30 ratio, without inhibitors (a, c, d), or with the addition of 100 μM zVAD-fmk (b), 100 μM YVAD-fmk (b), bafiolmycin A (g) or cytochalasin D (g) to the cultures before stimulation. Secretion and processing of IL-1β was determined by immunoblot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (a, b, d, g). Secretion of active caspase-1 cleavage products (p20 and CARD, human; p10, mouse) was determined by immunoblot (a, b, d, g). (c) Caspase-1 activation after 30 min with LPS Nigericin or upon contact with Eh in which active caspase-1 was stained with YVAD-FLICA, red; mammalian nuclei, blue (Eh nuclei are not stained). (e, h) Localization of endogenous NLRP3 after stimulation with Eh or LPS Nigericin. (f, h) Localization of F-actin after Eh stimulation; CFSE-labeled Eh, purple. Eh, E. histolytica; Mϕ, macrophages; Baf, bafiolmycin A; CytoD, cytochalasin D; MSU, monosodium urate; SN, supernatants; LYS, cell lysates. Scale bars, 10 μM. Data are representative of three separate experiments (error bars SEM). ***P < 0.005. We have previously shown that intact ameba directly in contact with macrophages triggers inflammasome activation, while soluble components of whole Eh, even after extended culture, do not [8]. We observed that intercellular contacts formed between Eh and macrophages were dependent on the major Eh surface adhesin, the Gal-lectin, and that Gal-lectin-mediated contact was necessary for inflammasome activation. In contrast, soluble Eh-Gal-lectin did not stimulate the inflammasome and competitively inhibited Eh-contact-from triggering inflammasome activation [8]. These data suggested the inflammasome involved is a selective sensor for Eh contact and furthermore, that signaling at the point of contact critically regulates inflammasome activation.

To determine which type of inflammasome was involved we used pharmacological inhibitors of the NLRP3 inflammasome and found these abrogated Eh-induced caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage and secretion in human THP-1 macrophages (S1A–S1C Fig). To verify whether the NLRP3 inflammasome was required, we performed siRNA knockdown of NLRP3 and the adaptor ASC in human macrophages, which inhibited the cleavage and secretion of caspase-1 and IL-1β (S2A and S2B Fig). Similarly, caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage and secretion did not occur in nlrp3-/- and asc-/- BMDMs stimulated with Eh (Fig 1D). These data established that NLRP3 is the inflammasome activated by Eh contact. Interestingly, we observed that NLRP3 redistributed to the cell periphery and intensely localized at Eh-macrophage junctions (Fig 1E). This localization pattern was dramatically different from unstimulated macrophages, where NLRP3 was dispersed throughout the cytoplasm, and from cells stimulated with soluble NLRP3 inflammasome activators LPS and nigericin, where NLRP3 organized in cytoplasmic puncta (Fig 1E). These data indicate that attachment of Eh to macrophages triggers recruitment of NLRP3 to the microenvironment near the point of contact and that this is a critical step in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Macrophages undergo dramatic cytoskeletal reorganization upon contact with Eh where F-actin accumulates at the intercellular junction similar to NLRP3 (Fig 1F). This led us to ask whether actin remodeling was required for Eh to recruit and induce NLRP3 activation. Addition of cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of F-actin inhibited caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage and secretion in response to Eh (Fig 1G). Several NLRP3 stimuli require actin-dependent phagocytosis to initiate phagolysosomal damage [11–13], though we suspected this pathway was not involved because Eh induced caspase-1 and IL-1β release within 10 min (Fig 1A), and phagolysosomal-induced activation of NLRP3 takes several hours [11–13]. To confirm this we cultured macrophages in bafilomycin to block endosome acidification, which is essential for phagolysosomal damage to activate NLRP3. While bafilomycin inhibited inflammasome activation in response to monosodium urate, which is phagocytosis-dependent, it had no effect on Eh-induced activation (Fig 1G). Microtubules have been reported to universally regulate the activation of NLRP3 by relocating mitochondria into the proximity of NLRP3 on the endoplasmic reticulum [14]. However, inhibition of tubulin polymerization with colchicine did not suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation by Eh. Instead, it significantly enhanced activation, indicating that the microtubule system is not required for Eh-induced NLRP3 activation (S3 Fig). Furthermore, cytochalasin D abrogated NLRP3 recruitment into contact sites (Fig 1H), indicating these are signaling-rich locations that regulate NLRP3 recruitment through an actin-dependent pathway. Based on this, we hypothesized that NLRP3 activation was regulated by a surface receptor in the intercellular junction that is connected to the actin cytoskeleton.

α5β1 integrin is activated by Eh contact via a surface-bound-integrin-binding E. histolytica cysteine protease

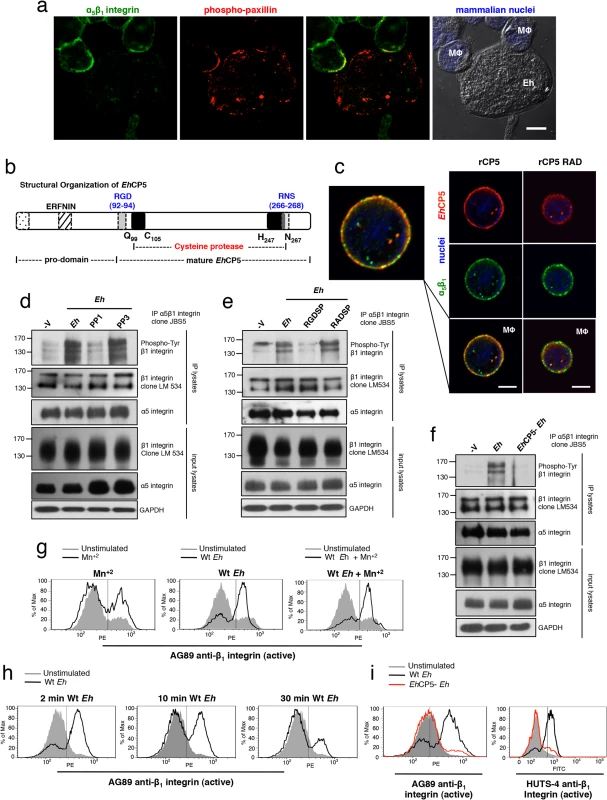

We were interested in host receptors that could function as sensors for distinguishing contact with the Eh surface. To this end, we recently identified that Eh cysteine protease 5 (EhCP5), a secreted cysteine protease that associates on the membrane of Eh, activates epithelial αvβ3 integrin via an RGD sequence [15]. Integrins are transmembrane receptors that connect with the cytoskeleton to control cell adhesion and processes dependent on cytoskeletal remodelling [16]. In addition to being regulated by ligand binding, their level of activation depends on receptor density and the size of the contact surface with which they interact [16]. These features could allow integrins to distinguish contact with a microbial surface if a ligand was present at the cell-cell interface.

Confocal immunofluorescence revealed that α5β1 integrin and phosphorylated-paxillin, a scaffold protein that is recruited to and phosphorylated at sites where integrins are active, were highly concentrated at Eh-macrophage contacts (Figs 2A and S4). Further analysis revealed that EhCP5 contains an RNS accessory sequence, which in human fibronectin synergizes with the RGD to bind and activate α5β1 integrin [17] (Fig 2B). Indeed, we found that recombinant EhCP5 (rEhCP5) immunoprecipitated with α5β1 integrin (S5 Fig) and co-localized with α5β1 integrin on the surface of macrophages (Fig 2C). In contrast, rEhCP5 in which the RGD was mutated to RAD did not immunoprecipitate or co-localize with α5β1 integrin on the surface of macrophages (Figs 2C and S5), showing that EhCP5 interacted with α5β1 integrin in an RGD-dependent manner. Note that rEhCP5 with the mutated RGD motif was still taken up by macrophages, likely by pinocytosis. However, it did not label nor co-localize with α5β1 integrin on macrophage surfaces (Fig 2C).

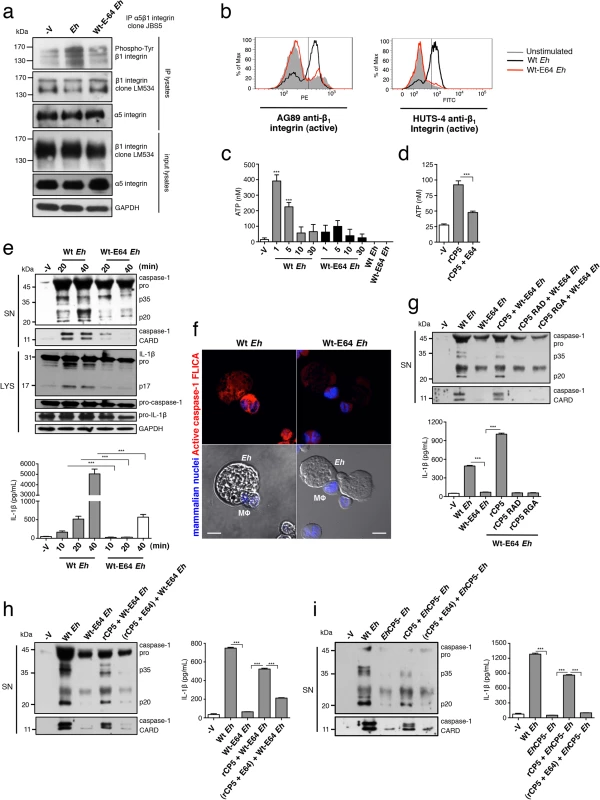

Fig. 2. α5β1 integrin is activated by Eh contact via a surface-bound-integrin-binding Eh cysteine protease.

(a) Localization of α5β1 integrin (green) and phosphorylated (active)-paxillin (red) in PMA-differentiated macrophages at sites of Eh contact; mammalian nuclei, blue (Eh nuclei are not labeled). (b) Diagram showing structural organization of EhCP5. (c) Subcellular distribution of EhCP5 (red) and α5β1 integrin (green) after THP-1 macrophages were cultured with rCP5 (left) or rCP5 in which the RGD site was mutated to RAD (right); nuclei, blue. (d-f) Immunoblot analysis of β1 integrin tyrosine phosphorylation (clone PY20) of anti-α5β1 integrin immunoprecipitates from PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated with Wt Eh (d-f), with PP1 or PP3 control (d), or blocking peptide RGDSP or RADSP control (e) added to cultures 10 min before stimulation, or EhCP5- Eh (f). (g-i) Activation status of β1 integrin in PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated with Wt (g-i), or EhCP5- Eh (i) evaluated with anti-β1 integrin mAbs, AG89 (g-i) and HUTS-4 (i) that recognize the active conformation specific epitope of β1 integrin. Scale bars, 10 μM. Data are representative of two (a, c, i) or three (d-h) separate experiments. We then sought to determine the activation status of α5β1 integrin upon Eh contact. The cytoplasmic domain of β1 integrin contains two tyrosine residues in conserved NPXY and NXXY motifs that are phosphorylated by Src family kinases (SFK) upon α5β1 integrin activation and are essential for recruiting adaptors that facilitate coupling of the integrin to the actin cytokskeleton and for maintaining it in an active state [18]. Immunoprecipitation of α5β1 integrin followed by anti-phospho-tyrosine immunoblot of THP-1 macrophages stimulated with Eh detected 160 kDa, 140 kDa and 120 kDa phospho-bands reported for β1 integrin [19] (Fig 2D). Eh-induced phosphorylation of the β1 subunit occurred in an SFK-dependent manner, as phosphorylation was inhibited by PP1 but not the inactive analog PP3 (Fig 2D). To test whether phosphorylation was dependent on an RGD-containing ligand, we used a soluble RGDSP peptide, which competes out binding and activation of RGD-binding integrins. The RGDSP peptide, but not the RADSP control inhibited Eh-induced phosphorylation of the β1 subunit in α5β1 integrin immunoprecipitates (Fig 2E).

To determine whether EhCP5 induced α5β1 integrin phosphorylation, we stimulated macrophages with Eh that were stably silenced for EhCP5 (hereafter designated EhCP5- Eh) and found that, in contrast to wildtype (Wt) Eh, EhCP5- Eh did not induce phosphorylation of the β1 subunit (Fig 2F). We further evaluated the activation status of the β1 subunit using two monoclonal antibodies AG89 and HUTS-4, which recognize the active conformation specific epitope of β1 integrin and performed flow cytometry to evaluate whether Eh enhanced its expression. The active epitope, which was basally expressed on unstimulated THP-1 macrophages, was rapidly and transiently increased upon addition of Wt Eh and was not further enhanced by the addition of Mn+2 which stabilizes the β1 subunit active conformation (Fig 2G–2I), whereas EhCP5- Eh did not induce the active β1 epitope (Fig 2I). Interestingly, though soluble EhCP5 interacted with α5β1 integrin, it neither induced phosphorylation of α5β1 integrin nor expression of the active β1 epitope. Together, these data showed that α5β1 integrin was specifically activated by EhCP5 upon contact and suggested that α5β1 integrin may sense Eh adhesion that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome.

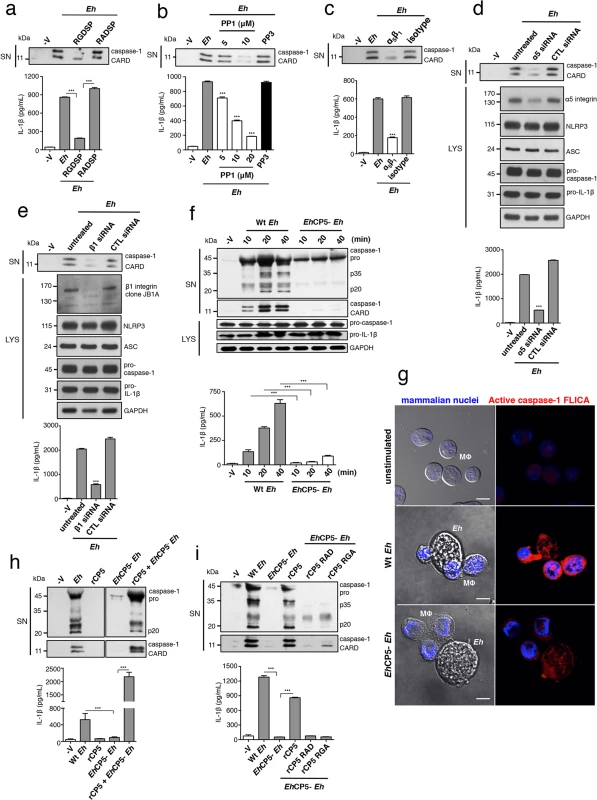

α5β1 integrin activation and EhCP5 are required for E. histolytica to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome

We next addressed whether α5β1 integrin is required for Eh to trigger the NLRP3 inflammasome. First we tested if activation of an RGD-binding integrin was required. Addition of soluble RGDSP, but not the RADSP control, inhibited caspase-1 and IL-1β activation by Eh (Fig 3A). SFKs are activated upon integrin ligation during the proximal signaling cascade [18]. Addition of the SFK inhibitor PP1, but not the inactive analog PP3, dose-dependently blocked caspase-1 and IL-1β activation by Eh (Fig 3B). These data showed that signaling of an RGD-binding integrin is required for Eh to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. We therefore investigated whether α5β1 integrin was involved. THP-1 macrophages express three RGD-binding integrins: α5β1, α4β1 and αvβ3 [20–22]. Function blocking antibodies to the β1 subunit, α5 subunit and to α5β1 integrin, but not to the α4 subunit or to αvβ3 integrin, abrogated caspase-1 and IL-1β secretion (Figs 3C, S6A and S6C). We further confirmed these results with siRNA knockdown of either β1 or α5 integrin in THP-1 macrophages, which did not alter expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome components (Fig 3D and 3E). Knockdown of either subunit prevented caspase-1 and IL-1β activation (Fig 3D and 3E). Therefore, α5β1 integrin is required for Eh to trigger the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Fig. 3. α5β1 integrin activation and EhCP5 are required for E. histolytica (Eh) to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.

(a-f, h, i) Immunoblot analysis of secreted active caspase-1 cleavage products and IL-1β enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated for 30 min or the indicated time with live Eh at a 1:30 ratio, without inhibitors (f, h, i), or with the addition of integrin RGD blocking peptide RGDSP or RADSP control (50 μM) (a), or SFK inhibitor PP1 or PP3 control (b), or a function blocking antibody to α5β1 integrin (10 μg mL-1) (c) added to cultures 10 min before stimulation, or following siRNA knockdown of α5 integrin (d) and β1 integrin (e). (d, e) Immunoblot analysis of α5 integrin (d) and β1 integrin (e) and inflammasome molecules following siRNA knockdown. (f, h, i) Macrophages stimulated with Wt or EhCP5- Eh with the addition of rCP5 (1 μg mL-1) (h, i), or rCP5 in which the RGD site was mutated to RAD or RGA (rCP5 RAD, rCP5 RGA respectively; 1 μg mL-1) (i) to cultures. (g) Caspase-1 activation upon contact with Wt or EhCP5- Eh in which active caspase-1 was stained with YVAD-FLICA, red; mammalian nuclei, blue (Eh nuclei are not stained). Scale bars, 10 μM. Data are representative of two (g, h) or three (a-f, i) separate experiments (error bars SEM). ***P < 0.005. As we identified EhCP5 as a ligand for activating α5β1 integrin, these results predicted that EhCP5 would be necessary for Eh to activate the inflammasome. We measured caspase-1 and IL-1β activation in macrophages stimulated with EhCP5- Eh and found that in contrast to Wt Eh, EhCP5- Eh did not activate the inflammasome (Figs 3F, 3G and S7A). There was no difference in caspase-1 and IL-1β activation when macrophages were stimulated with the vector control strain (S7B Fig; see Material and Methods for strain designation). Though soluble rEhCP5 alone did not trigger inflammasome activation, which is consistent with the fact that soluble rEhCP5 did not activate α5β1 integrin, when it was simultaneously applied with EhCP5- Eh, rEhCP5 restored caspase-1 and IL-1β activation (Fig 3H). This is likely due to EhCP5 being able to associate on the membrane of Eh after it is secreted, still allowing EhCP5 and α5β1 integrin to interact and reorganize into the junction and therefore to permit α5β1 integrin activation. To confirm that the RGD sequence was critical for EhCP5 to activate NLRP3, rEhCP5 in which the RGD sequence was mutated to RAD or RGA were tested for their ability to restore inflammasome activation to EhCP5- Eh. Unlike Wt rEhCP5, neither rEhCP5-RAD nor rEhCP5-RGA restored caspase-1 and IL-1β activation to EhCP5- Eh (Fig 3I). Thus, EhCP5 interacts with α5β1 integrin in an RGD-dependent manner to trigger activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

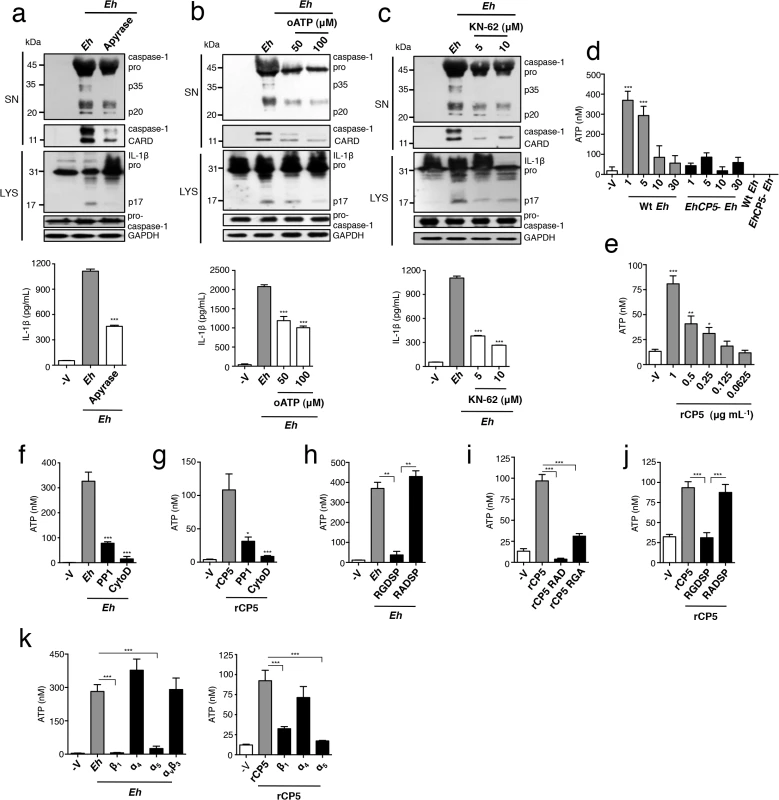

ATP release via α5β1 integrin is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation by Eh

We next sought to identify how α5β1 integrin regulates NLRP3 activation. In our hands the kinetics and strength of caspase-1 and IL-1β activation in response to Eh is similar to ATP stimulation of NLRP3. ATP is a well-established physiological stimulus of the NLRP3 inflammasome that signals through the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor (P2X7R), and it was of interest to us that P2X7R complexes with integrins, as it suggested that α5β1 integrin may regulate this pathway [23]. We therefore investigated whether ATP-P2X7R signaling was involved in NLRP3 activation upon Eh contact. We cultured macrophages with apyrase, which hydrolyses ATP to AMP and PPi, and this reduced caspase-1 and IL-1β activation in response to Eh (Fig 4A). Similarly, specific antagonists of the P2X7R, oATP and KN-62, inhibited caspase-1 and IL-1β activation, indicating an essential role for ATP-P2X7R signaling (Fig 4B and 4C). We then measured extracellular ATP in Eh-macrophage cultures. Naïve macrophages (negative control) released low levels of ATP whereas Eh released none (Fig 4D). However, when the two were placed together, we observed a rapid spike of extracellular ATP that diminished in a time-dependent fashion due to ubiquitously expressed ecto-ATPases that rapidly degrade extracellular ATP [24] (Fig 4D). Eh did not cause macrophage lysis that could account for the rapid burst of ATP, as there was no LDH release or trypan blue staining, even up to 30 minutes. We considered whether ATP release was induced by EhCP5 activation of α5β1 integrin and made a series of striking observations. Our first observation was that EhCP5- Eh did not stimulate ATP release (Fig 4D). We found that soluble rEhCP5 dose-dependently induced ATP, though the level was much lower than with intact Eh (Fig 4E). Therefore, EhCP5 is essential for triggering ATP, which it can induce directly from macrophages, but its activity is enhanced by Eh contact. This pointed to a role for formation of actin-dependent contacts in regulating ATP release. When we inhibited actin polymerization in macrophages by adding cytochalasin D, ATP release was completely abolished in response to both Eh and rEhCP5 (Fig 4F and 4G).

Fig. 4. ATP release via α5β1 integrin is required for E. histolytica (Eh) to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.

(a, b, c) Immunoblot analysis of active caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage products and IL-1β enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated for 30 min with Wt Eh with the addition of apyrase (30 U mL-1) (a), or P2X7R inhibitors oATP (50–100 μM) (b), or KN-62 (5–10 μM) (c). (d-k) ATP release from PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated for 1 min with or the indicated time with a 1:30 ratio of Wt Eh (d), EhCP5- Eh (d), or rCP5 (e), rCP5 RAD (i), rCP5 RGA (1 μg mL-1 or indicated concentration) (i) without inhibitors or with PP1 control (10 μM) (f, g), or cytochalasin D (10 μM) (f, g), or RGDSP peptide or RADSP control (h, j) (25 μM), or function blocking antibodies to β1, α4, and α5 integrin, αvβ3 integrin (10 μg mL-1) (k) added to cultures 10 min before stimulation or 45 min before stimulation for cytochalasin D. Data are representative of two (d, h-k) or three (a-c, e-g) separate experiments (error bars SEM). ***P < 0.005, *P < 0.05. oATP, oxidized adenosine triphosphate. Next we tested if ATP release required α5β1 integrin activation. Addition of soluble RGDSP and the SFK inhibitor PP1, but not soluble RADSP or PP3 controls, abolished ATP secretion in response to Eh, demonstrating that activation of an RGD-binding integrin was essential (Fig 4F and 4H). Consistent with this, the integrin-binding site of rEhCP5 was critical to stimulate ATP, as neither rEhCP5-RAD nor rEhCP5-RGA induced ATP release and soluble RGDSP blocked ATP by rEhCP5 (Fig 4I and 4J). Furthermore, inhibition of SFKs by PP1 abrogated ATP release by rEhCP5 (Fig 4G). Thus, although we did not detect α5β1 integrin phosphorylation or expression of the active β1 epitope in response to soluble rEhCP5, a low level of integrin activation occurred that caused some ATP release. Finally, to establish that α5β1 integrin was essential for releasing ATP we cultured macrophages with function-blocking antibodies to the three RGD-binding integrins expressed on THP-1 macrophages, α5β1, α4β1 and αvβ3. Similar to the results obtained for inflammasome activation, only antibodies that blocked the α5 and β1 subunits, and not α4 subunit and αvβ3, inhibited ATP release in response to both Eh and rEhCP5 (Fig 4K). Activation of α5β1 integrin by EhCP5 therefore, induced the rapid release of ATP into the extracellular space that was critical to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Furthermore, we conclude that a high threshold of α5β1 activation is reached only by contact, guaranteeing that a high concentration of extracellular ATP only occurs when Eh is directly present.

Panx-1 channels release ATP in response to E. histolytica

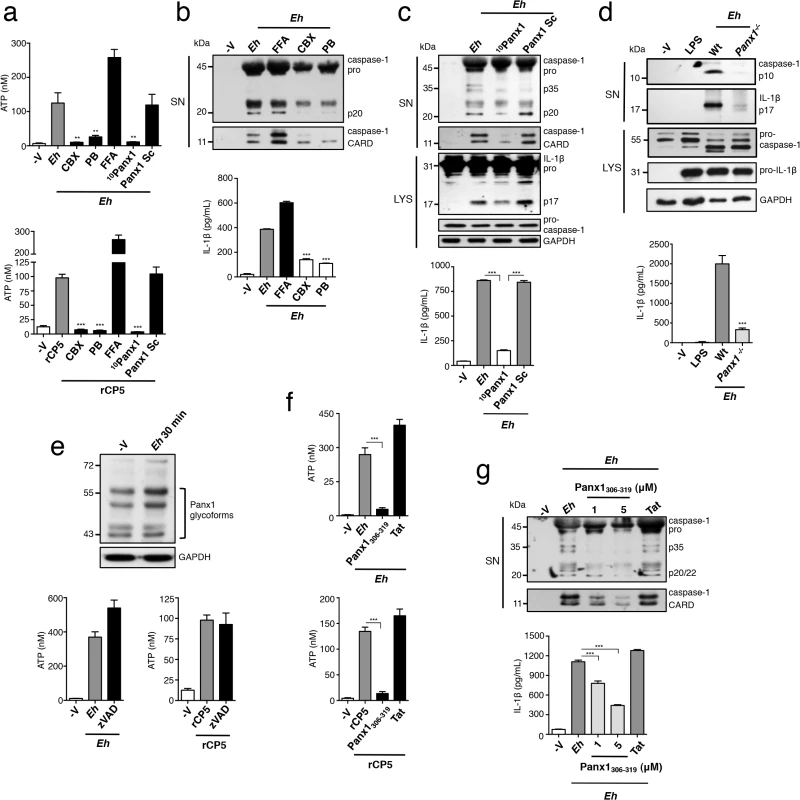

ATP is conducted into the extracellular space by non-junctional (hemi)-channels of the pannexin and connexin families [25]. To test whether Eh induced ATP release through either of these channels we applied inhibitors to macrophage cultures. We found that carbenoxolone (CBX) and probenecid (PB), a dual antagonist of pannexin and connexin channels and a pannexin-specific antagonist, respectively completely abolished ATP release in response to Eh and rEhCP5 (Fig 5A). In contrast, the connexin-specific inhibitor flufenamic acid (FFA) did not block ATP release; in fact FFA significantly enhanced ATP secretion (Fig 5A). Correspondingly, CBX and PB completely abolished Eh-induced activation of caspase-1 and IL-1β, whereas FFA enhanced the response. Thus, levels of extracellular ATP tune the degree of inflammasome activation (Fig 5B). Furthermore, these data suggested that ATP release occurred through a pannexin channel. Of the three pannexins, Panx1 is known to conduct ATP [26]. Incubation of macrophages in a mimetic blocking peptide of Panx1, 10Panx1 corresponding to the first extracellular loop of Panx1, but not a scrambled control, abolished ATP release in response to Eh and rEhCP5, and prevented activation of caspase-1 and IL-1β [27] (Fig 5A and 5C). Similarly, we found that panx1-/- macrophages, which had a normal inflammasome response to extracellular application of ATP and is consistent with other reports [28, 29], did not activate the inflammasome in response to Eh (Fig 5D). Together, these data indicate that Panx1 channels conduct ATP into the extracellular space triggered by activation of α5β1 integrin by EhCP5.

Fig. 5. Panx-1 channels release ATP in response to E. histolytica (Eh).

(a, e, f) ATP release from PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated for 1 min with a 1:30 ratio of Wt Eh or rCP5 (1 μg mL-1) with connexin/pannexin channel dual inhibitor carbenoxolone (CBX, 100 μM) (a), or pannexin channel inhibitor probenecid (PB, 250 μM) (a), or connexin channel inhibitor flufenamic acid (FFA, 100 μM) (a), or Panx1-peptide inhibitor 10Panx1 (500 μM) or scrambled control (500 μM) (a), or zVAD-fmk (100 μM) (e), or a mimetic peptide corresponding to an SFK-like consensus sequence of Panx1, Panx1306-319 (1 μM) or Tat control (1 μM) (f) added to cultures 10 min before stimulation or 45 min before stimulation for zVAD. (c-d, g) Immunoblot analysis of active caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage products and IL-1β enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages (c, b, g) or BMDMs (d) stimulated for 30 min with a 1:30 ratio of Wt Eh without inhibitors (d) or with addition of CBX (b), PB (b), FFA (b), 10Panx1 (c) or Panx1306-319 (g) as in (a) and (f), respectively. (e) Analysis of Panx1 expression following stimulation of THP-1 macrophages for 30 min with Eh. Data are representative of two (a, f, d) and three separate (b, c, g, e) experiments (error bars SEM). ***P < 0.005. A recent study demonstrated that caspases 3 and 7 regulate Panx1 opening by cleaving the C-terminus of Panx1 during apoptosis, and Eh can activate caspase 3 [30, 31]. To test whether α5β1 integrin activation lead to caspase-dependent opening of Panx1 we assessed Panx1 for cleavage after Eh contact, assuming that the C-terminal directed Panx1 antibody would show either a mobility shift or decrease in band intensity of Panx1, as was previously reported [30]. However, we observed no changes to Panx1 in Eh-stimulated macrophage lysates (Fig 5E). To address this further we applied the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD and measured ATP release. We found that zVAD did not inhibit ATP release in response to Eh or to rEhCP5, ruling out possibility of this pathway (Fig 5E).

Activation of purigenic receptors and NMDA receptors leads to SFK-dependent opening of Panx1, raising the possibility that α5β1 integrin activates SFKs to directly regulate Panx1 [32, 33]. A conserved SFK phosphorylation site has been identified at Y308 in the C-terminus of mouse Panx1, which corresponds to Y309 of human Panx1 [32]. An interfering C-terminal peptide corresponding to this conserved region has been used to attenuate opening of Panx1 in response to SFK-dependent signaling [32]. To investigate whether SFK phosphorylation of Panx1 at Y309 was involved we applied the small interfering sequence comprising the amino acids 306–319 of human Panx1 fused to a TAT sequence for membrane permeability, which is the same sequence that was used to block opening of mouse Panx1. This region of Panx1 is 100% conserved between mouse and human, which additionally suggests this region of Panx1 is critical for function. Application of the interfering peptide, which we termed Panx1306-319, inhibited ATP release in response to Eh and to rEhCP5, while the TAT control peptide did not (Fig 5F). Furthermore, Panx1306-319 but not the Tat control does-dependently inhibited Eh-induced activation of caspase-1 and IL-1β (Fig 5G). Our data therefore, indicate that activation of α5β1 integrin upon ligation of EhCP5 leads to SFK phosphorylation of Panx1 and opening of the channel to mediate rapid release of ATP.

EhCP5 cysteine protease activity is required to activate α5β1 integrin, ATP release and the NLRP3 inflammasome

Besides its integrin-binding RGD sequence, the cysteine protease is the major functional domain of EhCP5 [34]. We examined whether the cysteine protease played a role in activating α5β1 integrin and the pathway leading to NLRP3 activation. Wt Eh were grown overnight in presence of the irreversible cysteine protease inhibitor E-64 (hereafter referred to as Wt-E64 Eh), remain viable and express enzymatically inactive EhCP5 [35]. We first tested their ability to activate α5β1 integrin. To our surprise Wt-E64 Eh did not induce phosphorylation of α5β1 integrin or expression of the active β1 epitope (Fig 6A and 6B). Thus, the cysteine protease was essential to induce activation of α5β1 integrin, and indicated it would be essential to induce ATP release and inflammasome activation. We found that Wt-E64 Eh and rEhCP5 that was first inactivated in E-64 did not induce ATP release (Fig 6C and 6D). As predicted by these data, Wt-E64 Eh did not activate caspase-1 or IL-1β (Fig 6E and 6F). Addition of rEhCP5 to Wt-E64 Eh restored inflammasome activation in an RGD-dependent manner (Fig 6G) while, addition of rEhCP5 in which cysteine protease activity was abolished did not restore inflammasome activation to Wt-E64 Eh or to EhCP5- Eh (Fig 6H and 6I). Therefore, the cysteine protease and the RGD sequence of EhCP5 are essential to trigger α5β1 integrin-induced ATP release to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Note that α5β1 integrin does not undergo cleavage upon Eh contact and we were not able to identify the proteolytic target of EhCP5 triggering α5β1 integrin activation. Our data indicated the combined role of EhCP5 RGD sequence and cysteine protease was to induce ATP release that stimulates NLRP3. To determine if this was the singular function of EhCP5, we added exogenous ATP to macrophages stimulated with EhCP5- Eh or Wt-E64 Eh (this concentration of ATP together with TLR agonists stimulates NLRP3). Unexpectedly, exogenous ATP did not restore inflammasome activation (S8 Fig). This indicates that EhCP5 initiates additional signalling that is critical for NLRP3 activation, which might involve α5β1 integrin or other surface receptors.

Fig. 6. EhCP5 cysteine protease activity is required to activate α5β1 integrin, ATP release and the NLRP3 inflammasome.

(a) Immunoblot analysis of β1 integrin tyrosine phosphorylation (clone PY20) of anti-α5β1 integrin immunoprecipitates from PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated with Wt Eh or Wt-E64 Eh. (b) Activation status of β1 integrin in THP-1 macrophages stimulated with Wt Eh or Wt-E64 Eh evaluated with anti-β1 integrin mAbs, AG89 and HUTS-4 that recognize the active conformation specific epitope of β1 integrin. (c, d) ATP release from THP-1 macrophages stimulated for 1 min with a 1:30 ratio of Wt Eh or Wt-E64 Eh, or rCP5 (1 μg mL-1), or rCP5 inactivated first in E-64 (100 μM). (e, g, h, i) Immunoblot analysis of IL-1β and caspase-1 activation and IL-1β enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated for 30 min or indicated time with Wt Eh (e, g, h, i), Wt-E64 Eh (e, g, h), EhCP5- Eh (i) alone or with the addition of rCP5 (1 μg mL-1) (g, h, i), rCP5 RAD (g), rCP5 RGA (g) or rCP5 inactivated in E-64 (100 μM) (h, i). (f) Caspase-1 activation upon contact with Wt or Wt-E64 Eh in which active caspase-1 was stained with YVAD-FLICA, red; mammalian nuclei, blue (Eh nuclei are not stained). Scale bars, 10 μM. Data are representative of two (c, f) or three (a, b, d, e, g-i) separate experiments (error bars SEM). ***P < 0.005. EhCP5 and the NLRP3 inflammasome control intestinal IL-1β responses

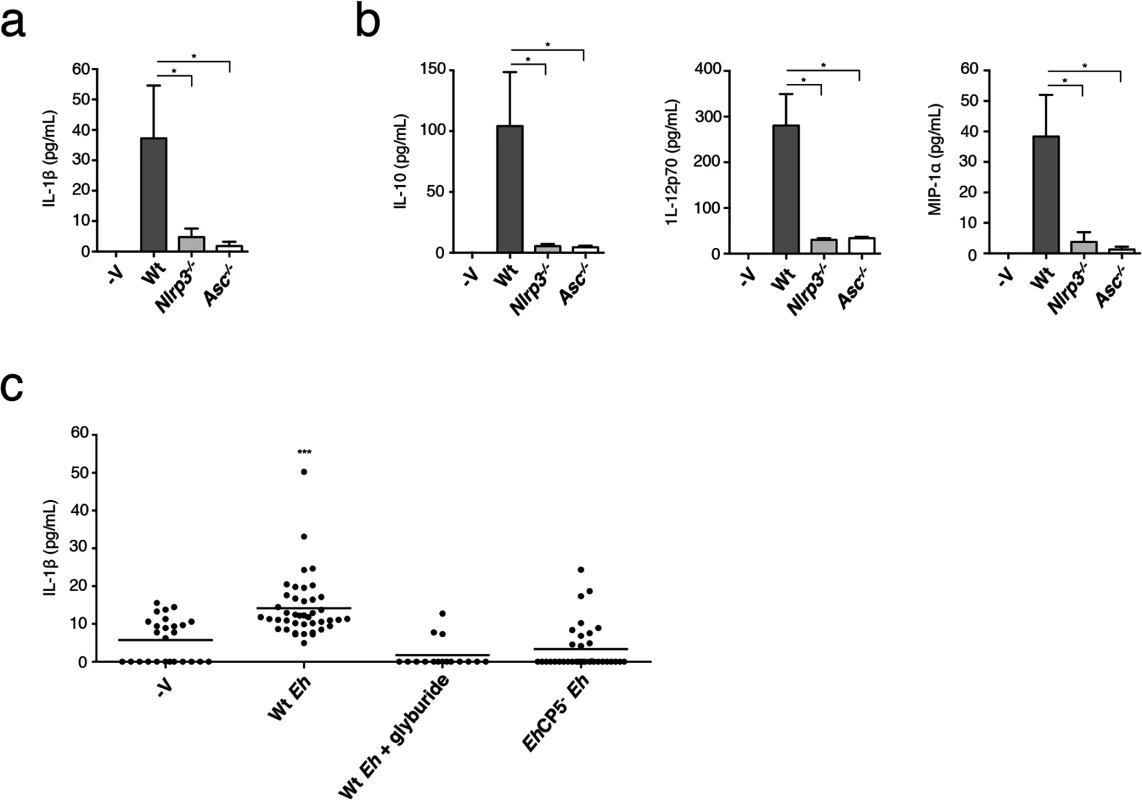

During acute Eh infection rapid innate immune responses are vital for early detection and swift responses to invasion across the mucosal barrier to restrict and eliminate infectious spread. To define whether NLRP3 inflammasome activation regulates IL-1β secretion during acute Eh infection, we compared the early innate response at 3 h in closed proximal colonic loops of mice infected with Eh. In this model we observe a rapid secretory response characterized by distension of the colon by intense luminal secretions that are comprised of water, mucus, variable amounts of blood and pro-inflammatory cytokines [36]. This is consistent with the human disease where invasion by Eh most often causes diarrhea and dysentery [1]. Gross pathology was similar between Wt and nlrp3-/- animals. asc-/- animals, however, tended towards a more severe response with visible bloody luminal exudates, inflamed dilated blood vessels and a larger secretory response. To determine IL-1β secretion we measured cytokine secretion in luminal exudates of infected animals. While there was IL-1β in luminal exudates of Wt mice, it was virtually undetectable in the luminal secretions of nlrp3-/- and asc-/- mice (Fig 7A). Furthermore, other inflammation-related cytokines were absent in nlrp3-/- and asc-/- mice (Fig 7B). To address whether IL-1β secretion occurs during invasion in human colonic tissues, we incubated healthy human colonic biopsies for 3 h with Eh in the presence or absence of the NLRP3 inhibitor glyburide. Glyburide was not directly toxic to Eh and Eh treated with glyburide activate the inflammasome. As predicted, glyburide completely abrogated IL-1β secretion (Fig 7C). We previously established that EhCP5- Eh do not induce IL-1β in the colonic loop model [36]. To test this in human colon we measured IL-1β secretion from human biopsies stimulated with EhCP5- Eh. In contrast to Wt Eh, EhCP5- Eh did not elicit IL-1β from human colon (Fig 7C). Taken together, these data show that EhCP5-triggered activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and regulated IL-1β release during acute invasion of the intestinal mucosa.

Fig. 7. NLRP3 inflammasome is involved in E. histolytica-induced inflammatory responses of the colon.

Cytokine array of IL-1β (a), IL-12p70 (b), MIP-1α (b) and IL-10 (b) of luminal secretions from colons challenged with 1 x106 Wt Eh for 3 h (n = 4 per group). *P < 0.05 (unpaired Mann-Whitney test). (c) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of IL-1β secretion from normal healthy human colonic biopsies stimulated with Wt Eh with or without Glyburide (100 μM), or EhCP5- Eh for 3 h. Each symbol represents an individual biopsy (control, n = 26; Wt Eh, n = 46; Wt Eh + Glyburide, n = 16; EhCP5- Eh, n = 36) ***P < 0.005 (unpaired student’s t-test). Data are representative of one (a, b) and three or more pooled experiments (c). Discussion

The immune mechanisms that escalate the inflammatory response to invasive Eh have been amongst the most significant questions of the pathogenesis of amebiasis. We recently identified that attachment of Eh to macrophages mediated by Eh-Gal-lectin triggers inflammasome activation [8]. Until this point, direct contact of the parasite with cells of the innate immune system had not been recognized as an event that initiates inflammation. This lead us to speculate that engagement of surface receptors and their organization into the intercellular junction critically regulate inflammasome activation and this was a sensing mechanism for distinguishing immediate microbial contact to activate a highly potent inflammatory response. The present gap in knowledge of host receptors that interact with Eh-Gal-lectin needs to be addressed to understand how contacts with macrophages form and “adhesive” signaling that may regulate NLRP3 activation. However, because Eh-Gal-lectin was a prerequisite for adhesion, we considered if additional molecules on the surface of Eh engage surface receptors and contribute to Eh-sensing once principal contact has been established by Eh-Gal-lectin.

We had previously established that EhCP5, a cysteine protease both secreted and expressed on the surface of Eh could ligate αvβ3 integrin on colonic epithelia via an RGD sequence, which activated Akt and led to NF-κB-driven production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [14]. In these studies this interaction was explored using the soluble protein and a fragment of EhCP5 containing the RGD-sequence. However, further sequence analysis revealed that EhCP5 contains an RNS sequence, which in fibronectin, a canonical ligand of α5β1 integrin, synergizes with the RGD to specify binding to α5β1 integrin. This indicated that EhCP5 was likely to interact with α5β1 integrin [16]. Additionally, given the essential role of integrins in cell adhesion and polarization and that key features that regulate their level of activation are the size of contact surfaces and receptor clustering, this raised the possibility that surface-bound EhCP5 could trigger integrin activation in a very different manner to soluble integrin ligation and that integrins could be involved in the ability of host cells to distinguish direct Eh contact [15]. This served as the basis to explore the role of integrins in contact-dependent activation of the inflammasome.

Here we found that NLRP3 is the inflammasome activated by direct Eh contact with macrophages and intriguingly, we observed recruitment of NLRP3 into the microenvironment of the intercellular junction, indicating that signaling from this location was critical to activate NLRP3. On the cell surface we saw that α5β1 integrin was strongly recruited and the presence of phosphorylated-paxillin revealed these were locations of active integrin signaling. We confirmed there was direct activation of α5β1 integrin upon Eh contact by showing there was SFK-dependent phosphorylation of the β1 subunit in immunoprecipitates of α5β1 integrin and expression of the active epitope of β1 integrin when macrophages were stimulated with Eh. As phosphorylation of the β1 subunit was inhibited by addition of a soluble RGD peptide, which prevents RGD-binding integrins from interacting with RGD-containing ligands, we investigated whether EhCP5 could ligate and activate α5β1 integrin. We found that soluble EhCP5 ligated α5β1 integrin, whereas EhCP5 with a mutated RGD sequence did not and that EhCP5-Eh did not induce phosphorylation of the β1 subunit or expression of the active β1 epitope. These data showed EhCP5 was responsible for activating α5β1 integrin upon contact. We could not, however, detect α5β1 integrin activation by these methods with soluble EhCP5, suggesting that α5β1 integrin could be involved in distinguishing direct Eh contact that lead to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. We tested this hypothesis by disrupting RGD interactions and SFK activation, which is critical to initiate integrin signaling, and both abolished inflammasome activation. A panel of integrin function-blocking antibodies against the RGD-binding integrins that are expressed on THP-1 macrophages revealed that only inhibition of α5β1 integrin could block inflammasome activation, which we corroborated by individually silencing expression of the α5 and β1 subunits. Thus, our data clearly show that activation of α5β1 integrin via direct contact with Eh was required to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.

In the immune system high concentrations of extracellular ATP is a danger signal and in macrophages activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in the setting of a pathogen stimulus. It was of interest to us that the rapid inflammasome activation by Eh paralleled the rate and magnitude of ATP stimulation. To understand how α5β1 integrin activation controlled NLRP3 we explored whether ATP functioned in this pathway. Hydrolysis of ATP and interference of P2X7R activation established that ATP was indeed involved and we showed that trophozoites and to a lesser degree soluble EhCP5 stimulated a burst of ATP, which required the activation of α5β1 integrin by EhCP5. We showed EhCP5 could directly trigger release of ATP from macrophages through its interaction with α5β1 integrin. Though we could not detect enhanced phosphorylation and expression of the active β1 epitope by soluble EhCP5, our data indicate that binding of soluble EhCP5 to some extent ‘tickled’ the integrin to stimulate a small amount of ATP release.

ATP can be released through pannexin and connexin channels, which allow the diffusion of ions across the plasma membrane [25]. In immune cells Panx1 appears particularly important for this [25]. We found that pannexin family and Panx1-specific channel blockers abolished ATP release and inflammasome activation by Eh. In further support, we tested Eh-induced inflammasome activation in Panx1-/- macrophages, which in our hands and reported by others activate the inflammasome normally in response to extracellular ATP [27, 28]. However, inflammasome activation did not occur in Panx1-/- macrophages stimulated by Eh. This fits with Panx-1 channels conducting ATP upon contact, such that when Panx1 is absent ATP is not released and the NLRP3 inflammasome is not activated. Finally to understand how α5β1 integrin could regulate opening of Panx1 we tested two possibilities. First, whether this was by caspase cleavage of the Panx1 intracellular C-terminus, which has been shown to regulate ATP release in apoptotic immune cells [29]. However, we ruled this pathway out as we never observed a band shift or disappearance of any Panx1 glycoforms after Eh stimulation and ATP release was not sensitive to pan-caspase inhibition. We considered whether another pathway involving SFK phosphorylation of a conserved region of the Panx1 intracellular C-terminus regulated ATP secretion. Though phosphorylation of Panx1 by SFKs has not been demonstrated directly, two groups have shown that SFKs can open Panx1 and an SFK consensus sequence has been identified in Y308 of mouse Panx1 [32, 33]. The region surrounding this sequence is completely conserved in human Panx1 and indicates this region is critical for Panx1 function. Using the same strategy employed by these groups, we showed that PP1 prevented ATP release and an interfering C-terminal peptide comprising the amino acids 309–319 of the Panx1 C-terminus, which covers the predicted SFK phosphorylation sequence, blocked ATP release and inhibited activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by Eh. Together our data suggest when α5β1 integrin is activated via direct contact with Eh, SFKs that become instantly active upon integrin activation, are involved in phosphorylating the Panx1 intracellular domain causing the channel to open and release ATP into the extracellular space.

Eh invasion initiates vigorous tissue inflammation. EhCP5- Eh are avriulent in models of Eh infection and elicit little inflammation indicating EhCP5 is essential for triggering inflammatory responses [15, 36–38]. Interestingly, an early report suggested if pro-IL-1β was released, Eh cysteine proteases could cleave IL-1β into the active form [39]. Our in vivo results in an animal model of acute Eh invasion and in intact human colonic biopsies cultured with the parasite indicate the NLRP3 inflammasome plays a significant role in regulating the pro-inflammatory response in acute intestinal amebiasis by regulating IL-1β responses in the colon.

In immune cells, signaling at intercellular junctions involving large-scale reorganization of surface receptors and intracellular signaling molecules, collectively termed ‘immune synapses,’ have long been recognized to control the activation of adaptive immune cells [40]. Recently, this concept was extended to microbial recognition by macrophages in deciphering particulate versus soluble ligands that bind to the same receptors but initiate different responses [41]. In this work the authors showed particulate fungal β glucan is distinguished from soluble β glucan as a result of Dectin-1 clustering and spatial exclusion of the phosphatase CD45, which triggered signaling that lead to phagocytosis and release of reactive oxygen, and is proposed as a mechanism to distinguish and activate direct anti-fungal responses only when fungi are immediately present [41]. Our data demonstrate that NLRP3 and α5β1 integrin cooperate to distinguish direct contact with extracellular microbes where NLRP3 is recruited into the synapse and undergoes activation via ATP signalling as a consequence of α5β1 integrin activation in the intercellular junction. In this way inflammasome-induced pro-inflammatory responses are restricted and localized to locations where Eh are present. This is reminiscent of other immune synapses in which long-range recruitment of molecules into the junction critically regulates their activity and cell activation. Contact-dependent release of ATP through opening of Panx1 was a critical part of the mechanism through which α5β1 integrin regulated NLRP3. Similarly, activation of T cell immune synapses requires a large burst of ATP through Panx1 [42, 43]. In this regard, the magnitude of ATP release that occurred following macrophage-Eh contact is similar to cross-linking the CD3 receptor on T cells and thus contact-dependent triggering of ATP may be another common feature regulating immune cell synapses.

A recent study revealed α5β1 integrin is involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activation by a soluble toxin Td92 from the periodontal pathogen Treponema denticola [44]. However, though soluble Td92 directly ligated α5β1 integrin through a non-RGD interaction, the mechanism through which NLRP3 was regulated by α5β1 integrin appears to be different to its role in sensing Eh contact. Td92 activated the inflammasome several hours after stimulation and required α5β1 integrin to activate NF-κB, which was essential not only for pro-IL-1β induction but also for caspase-1 activation [44]. Thus, α5β1 integrin likely regulated NLRP3 indirectly through a transcription-dependent event. In sensing Eh contact, however, α5β1 integrin engages post-translational signalling that rapidly triggers NLRP3. Taken together, this study and ours indicate α5β1 integrin is a critical receptor for detecting extracellular pathogens linked to the NLRP3 inflammasome. As α5β1 integrin is commonly exploited by microbial pathogens our data suggest it might be under immune-surveillance by NLRP3 for abnormal activity that would indicate pathogen presence.

In summary we have identified α5β1 integrin is a critical surface receptor in the intercellular junction that mediates rapid activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, enabling the host to distinguish direct contact with extracellular Eh and mobilize highly pro-inflammatory host defenses precisely at sites of Eh infection.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Ultra-pure LPS, PMA, apyrase, DPI, KCL, ATP, oATP, KN-62, cytochalasin D, bafilomycin, glyburide, E-64 were from Sigma. zVAD-fmk, YVAD-fmk were from Enzo Life Sciences. GRGDSP, GRADSP, PP1, PP3 were from Calbiochem. 10Panx1 (WRQAAFVDSY) and 10Panx1-scrambled peptides were from Anaspec. Integrin function blocking antibodies were from Millipore. MSU was a gift from Y. Shi (University of Calgary). Panx1309 and Tat peptides were a gift from R. Thompson (University of Calgary). Human and murine IL-1β secretion in cell culture was quantified by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems).

Animals

C57BL/6 mice were from Charles River. The following genetically modified mouse strains were used all on a C57BL/6 background: nlrp3-/- (D. Muruve and P. Beck, University of Calgary), asc-/- (D. Muruve and P. Beck, University of Calgary), panx1-/- (E. Lazarowski, University of North Carolina) and compared to Wt littermates. The University of Calgary Animal Care Committee approved experiments involving animals.

Cell preparation and stimulation

THP-1 human monocytic cells (ATCC) were plated onto 24 well plates at 4x105 cells/well with 50 ng/mL PMA in complete RPMI 1640 the night before treatment. Cells were stimulated with Eh or rEhCP5 proteins in 250 μL serum-free RPMI for the indicated times (1–40 min). For inhibitor studies THP-1 cells were pre-treated at 37°C unless otherwise stated with the indicated concentrations of zVAD-fmk (100 μM, 45 min), YVAD-fmk (100 μM, 45 min), DPI (25–100 μM, 30 min), KCL (90–200 mM was added to fresh serum-free media upon Eh), glyburide (100 μM, 30 min), cytochalasin D (5–10 μM, 30 min), bafilomycin (50–250 nM, 30 min), oATP (50–100 μM, 2 h), KN-62 (1–5 μM, 30 min), apyrase (20 U mL-1, 5 min), 10Panx1 (500 μM, 10 min RT), 10Panx1 scrambled (500 μM, 10 min RT), GRGDSP (50 μM, 10 min RT), GRADSP (50 μM, 10 min RT), integrin function-blocking antibodies (10 μg mL-1,10 min RT), PP1 (5–20 μM, 10 min, 1-(1,1-Dimethylethyl)-1-(4-methylphenyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine) and PP3 (10–20 μM, 10 min, 1-Phenyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine), Panx1309 (5–10 μM, 10 min RT), Tat (5–10 μM, 10 min RT) and changed into fresh serum-free media before stimulation with Eh unless otherwise stated. BMDM were prepared from the femurs and tibias of mice cultured for 6 days in 10% FBS-RPMI 1640 supplemented with 30% L-cell supernatant, then replated onto 24 well plates at 5x105 cells/well in complete RPMI 1640. On the day of experiment BMDM were treated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 3.5 h. Cells were stimulated with 1.5x104 Eh per well in 250 μL serum-free RPMI for the indicated time. As a control for the silencing technology in EhCP5- Eh we tested a vector control strain that has the same silencing technology as EhCP5- Eh. The EhCP5- Eh are also silenced for EhAPA gene. As a control for off-target effects and for contribution of EhAPA, we tested Eh that are only silenced for EhAPA, designated EhAPA- Eh, and these amoeba stimulated inflammasome activation similar to wildtype Eh. We concluded neither the silencing technology nor EhAPA altered the ability of Eh to stimulate inflammasome activation.

E. histolytica culture

E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS were grown axenically in TYI-S-3 medium with 100 U mL-1 penicillin and 100 μg mL-1 streptomycin sulfate at 37°C in sealed 15 mL borosilicate glass tubes as described previously [45]. To maintain virulence, trophozoites were regularly passed through gerbil livers as described [46]. Ameba were harvested after 72 h of growth by centrifugation at 200 x g for 5 min at 4°C and resuspended in serum-free RPMI. E. histolytica cultures deficient in EhCP5 and EhAPA (vector control) were a gift from D. Mirelman (Weizmann Institute of Science). To irreversibly inhibit Eh cysteine protease activity Eh were cultured overnight in E-64 (100 μM) as previously described [15].

siRNA and transfection

Control and siRNA for the indicated genes were from Dharmacon (OnTarget plus SMART pool siRNA). THP-1 cells were transfected with siRNA (100 nM) for 48 h using DOTAP transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by overnight PMA stimulation.

Generation and mutation of recombinant Eh Cysteine Protease 5

Expression plasmid pJC45 encoding the pro-form of EhCP5 (amino acids 14–317) was a gift from I. Bruchhaus (Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany). The RGD site of recombinant EhCP5 was mutated to RAD or RGA by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). Recombinant plasmids were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) [pAPlacIQ]. Recombinant proteins were expressed as insoluble histidine-tagged pro-enzymes and were solubilized, purified and refolded as previously described [34]. Protein purity was >95% as revealed by SDS-PAGE. To confirm that recombinant enzymes were active and mutation of the RGD motif did not alter proteolytic activity of recombinant EhCP5, cysteine protease activity was measured by cleavage of the fluorogenic cathepsin B substrate Z-Arg-Arg-AMC.

Immunoblot and immunoprecipitation

THP-1 or BMDM supernatants from 4 wells were pooled and centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at 2000g. Pelleted debris was discarded and supernatants were concentrated by TCA precipitation. For Western blotting, precipitated supernatants were resuspended in 50 μL Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min and equal volumes were resolved on 12.5% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. For cell lysates, plates were washed in cold PBS before lysis buffer (NaCL, Tris (pH 8), SDS, Triton 100-X, EDTA, PMSF, E-64, leupeptin, aprotonin, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)) and centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min at 14000g. For detection of phospho-proteins lysis buffer included NaF, Na3VO4. Equal amounts of proteins boiled for 5 min in Laemmli buffer were resolved on 7.5–12.5% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk or 3% BSA for phospho-proteins, incubated overnight at 4°C in primary Abs and visualized with secondary HRP-conjugated Abs. Supernatents were detected with SuperSignal Chemiluminescence Reagents (Pierce) and lysates with ChemiLucent ECL detection (EMD Millipore). Primary Abs were anti-IL-1β cleaved human (1 : 1000, 2021, Cell Signaling), anti-IL-1β human (1 : 700, 7884, Santa Cruz), anti-caspase-1 human (1 : 1000, 2225, Cell Signaling), anti-caspase-1 human (1 : 1000, 622, Santa Cruz), anti-IL-1β mouse (1 : 1000, AF401, R&D Systems), anti-caspase-1 mouse (1 : 1000, 514, Santa Cruz), anti-NLRP3 (1 : 1000, AG-20B-0014, Adipogen), anti-ASC (1 : 1000, 30153, Santa Cruz), anti-phosphotyrosine (1 : 1000, clone PY20, BD Biosciences), anti-β1 integrin (1 : 2000, 1981, Millipore), anti-α4 integrin (1 : 1000, 14008, Santa Cruz), anti-EhCP5 (1 : 1000, gift from S. Reed, University of San Diego), anti-GAPDH (1 : 10000, Jackson Laboratories). Antibodies against α5β1 integrin (Millipore, 1965) were used to precipitate proteins from cell lysates in the presence of 20 μL protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz) overnight at 4°C. Protein complexes were washed three times with lysis buffer and incubated at 95°C for 5 min and resolved by immunoblot analysis.

Confocal microscopy

For imaging of active caspase-1 THP-1 cells were seeded on glass coverslips and stimulated with Eh or LPS (25 ng mL-1) and nigericin (5 μM). Cells were washed in cold PBS and fixed in cold acetone for 5 min. YVAD-FLICA (FLICA 660-Caspase-1 reagent, Immunochemistry Technologies) at 1 : 70 dilutions was added for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed twice in PBS-Tween (0.1%) for 5 min and mammalian nuclei were stained with DAPI for 20 min, followed by 2 washes in PBS-Tween (0.1%) for 5 min. Cells were mounted onto slides and imaged immediately as YVAD-FLICA staining dissipates quickly after fixation. For imaging, α5β1 integrin, phosphorylated-paxillin and NLRP3 THP-1 cells were seeded on glass coverslips and stimulated with Eh. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min at RT and stained with antibodies against α5β1 integrin (Millipore, 1965, 1 : 250), phospho-paxillin (Tyr118) (Millipore, 07733, 1 : 250) or NLRP3 (Adipogen, AG-20B-0014, 1 : 200). Mammalian nuclei were stained with DAPI, F-actin was stained with Alexa fluor 647-conjugated phalloidin and in some instances Eh were labeled with CFSE. Cells were analyzed on an Olympus IX8-1 FV1000 Laser Scanning Confocal microscope with a 60x objective.

ATP measurement

The amount of ATP in the media was quantified using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometry-based monitoring of β1 integrin activation Eh were added to cells for the indicated time at 37°C. Cells were then washed with cold PBS and fixed in paraformaldehyde followed by addition of 2 different mAbs antibodies AG89 or HUTS-4, which recognize the active β1 integrin conformation-specific epitope and evaluated by flow cytometric analysis.

Ethics statement

The Health Sciences Animal Care Committee from the University of Calgary, have examined the animal care and treatment protocol (M08123) and approved the experimental procedures proposed and certifies with the applicant that the care and treatment of animals used will be in accordance with the principles outlined in the most recent policies on the “Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals” by The Canadian Council on Animal Care. Informed written consent was obtained from all adult patients. The Calgary Health Research Ethic Board at the University of Calgary approved this study.

Colonic biopsy studies

Fresh healthy colonic biopsies were obtained from patients undergoing routine screening for colon cancer. None of the patients were taking NSAIDs, aspirin or other anti-inflammatory medication within 7 days of the colonoscopy. Tissue were exposed to 5x105 Wt or EhCP5- Eh for 3 h in serum-free Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). IL-1β release into the supernatants was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Colonic loops

Mice (nlrp3-/-, asc-/- and C57BL/6 Wt littermates) were bred in a conventional facility and fasted 8 h before surgery. To generate a colonic loop, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and ligatures were generated 1 cm and 3 cm distal of the ileal-cecal junction. Colonic loops were injected with 1x106 log-phase virulent Eh. Sham challenged animals were injected with 200 μL of the vehicle PBS. Animals were kept on a 37°C heated blanket for 3 h. IL-1β, IL-12p70, MIP-1α and IL-10 were measured in the colonic loop exudates by multiplex cytokine array (Eve Technologies). The University of Calgary Animal Care Committee approved protocols for experiments involving animals.

Statistics

All experiments shown are representative of three independent experiments unless otherwise indicated. GraphPad Prism4 was used for statistical analysis. Treatment groups were compared using the paired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was assumed at P< 0.05. Results are displayed as mean +/ - standard error of the mean (SE). Colonic loop model was compared using the unpaired Mann-Whitney.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Stanley S.L. Ameobiasis. Lancet. 2003; 361 : 1025–1034. 12660071

2. Mortimer L., and Chadee K.. The Immunopathogenesis of Entamoeba histolytica. Exp. Parasitol. 2010; 126 : 366–380. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.03.005 20303955

3. Prathap K., and Gilman R. The histopathology of acute intestinal amebiasis. A rectal biopsy study. Am. J. Pathol. 1970; 60 : 229–246. 5457212

4. Chadee K., and Meerovitch E. Entamoeba histolytica: early progressive pathology in the cecum of the gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985; 34 : 283–291. 2858986

5. Lin J.Y, Chadee K. Macrophage cytotoxicity against Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites is mediated by nitric oxide from L-arginine. J. Immunol. 1992; 148 : 3999–4005. 1318338

6. Seguin R., Mann B., Keller K., and Chadee K. Identification of the galactose-adherence lectin epitopes of Entamoeba histolytica that stimulate tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995; 92 : 12175–12179. 8618866

7. Underhill D.M., and Goodrige H. Information processing during phagocytosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012; 12 : 492–502. doi: 10.1038/nri3244 22699831

8. Mortimer L., Moreau F., Cornick S., and Chadee K. Gal-lectin-dependent contact activates the inflammasome by invasive Entamoeba histolytica. Mucosal Immunol. 2014; 4 : 829–841. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.100 24253103

9. Latz E., Xiao S.T., and Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013; 13 : 397–411. doi: 10.1038/nri3452 23702978

10. Yamin T., Ayala J.M., and Miller D.K. Activation of the native 45 kDa precursor form of interlekuin-1 converting enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1996 : 271 : 13273–13282. 8662843

11. Hornung V., Bauernfeind F., Halle A., Samstad E.O., Kono H., Rock K.L., et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts mediate NALP-3 inflammasome activation via phagosomal destabilization. Nat. Immunol. 2008; 9 : 847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631 18604214

12. Halle A., Hornung V., Petzold G.C., Stewart C.R., Monks B.G., Reinheckel T., et al. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-b. Nat. Immunol. 2008; 9 : 857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636 18604209

13. Duewell P., Kono H., Rayner K., Sirois C., Vladimer G., Bauernfeind F.G., et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010; 464 : 1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938 20428172

14. Misawa T., Takahama M., Kozaki T., Lee H., Zou J., Saitoh T. et al. Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 2013; 14 : 454–460. doi: 10.1038/ni.2550 23502856

15. Hou Y., Mortimer L., and Chadee K. Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteinase 5 binds integrin on colonic cells and stimulates NFkappaB-mediated pro-inflammatory responses. J. Biol. Chem. 2010; 285 : 35497–35504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066035 20837477

16. Kinashi T. Intracellular signaling controlling integrin activation in lymphocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005; 5 : 546–559. 15965491

17. Ruoslahti E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 1996; 12 : 697–715 8970741

18. Bouvard D., Pouwels J., De Franceschi N., and Ivaska J. Integrin inactivators: balancing cellular functions in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Bio. 2013; 14 : 430–442. doi: 10.1038/nrm3599 23719537

19. Hirst R., Horwitz A., Bucko C., and Rohrschneider L. Phosphorylation of the fibronectin receptor complex in cells transformed by oncogenes that encode tyrosine kinases. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986; 83 : 6470–6474. 3018734

20. Kerur N., Veettil M.V., Sharma-Walia N., Sadagapan S., Bottero V., Paul A.G., et al. Characterization of entry and infection of monocytic THP-1 cells by Kaposi's sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV): Role of heparan sulfate, DC-SIGN, integrins and signaling. Virology. 2010; 406 : 103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.012 20674951

21. Chu C., Celik E., Rico F., and Moy V.T. Elongated membrane tethers, individually anchored by high affinity alpha(4)beta(1)/VCAM-1 complexes, are the quantal units of monocyte arrests. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e64187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064187 23691169

22. Ashida N., Arai H., Yamasaki M., and Kita T. Distinct signaling pathways for MCP-1-dependent integrin activation and chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276 : 16555–16560. 11278464

23. Kim M., Jiang L.H., Wilson H.L., North R.A., and Surprenant A. Proteomic and functional evidence for a P2X7 receptor signalling complex. EMBO J. 2001; 20 : 6347–6358. 11707406

24. Yegutkin G.G., Henttinen T., Samburski S.S., Spychala J., and Jalkanen S. The evidence for two opposite, ATP-generating and ATP-consuming, extracellular pathways on endothelial and lymphoid cells. Biochem. J. 2002; 367 : 121–128. 12099890

25. Lohman A.W., and Isakson B.E. Differentiating connexin hemichannels and pannexin channels in cellular ATP release. FEBS Lett. 2014; 588 : 1379–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.004 24548565

26. Adamson S.E., and Leitinger N. The role of pannexin1 in the induction and resolution of inflammation. FEBS Lett. 2014; 588 : 1416–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.03.009 24642372

27. Pelegrin P., and Surprenant A. Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1β release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 2006; 25 : 5071–5082. 17036048

28. Qu Y., Misaghi S., Newton K., Gilmour L.L., Louie S., Cupp J.E., et al. Pannexin-1 is required for ATP release during apoptosis but not for inflammasome activation. J. Immunol. 2011; 186 : 6553–6561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100478 21508259

29. Wang H., Xing Y., Mao L., Luo Y., Kang L., and Meng G. Pannexin-1 influences peritoneal cavity cell population but is not involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Protein Cell. 2013; 4 : 259–265. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-2114-1 23549611

30. Chekeni F., Elliot M.R., Sandilos J.K., Walk S.F., Kinchen J.M., Lazarowski E.R., et al. Pannexin 1 channelsmediate ‘find-me’ signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature. 2010; 467 : 863–867. doi: 10.1038/nature09413 20944749

31. Huston C.D, Boettner D.R., Miller-Sims V., and Petri W.A. Apoptotic killing and phagocytosis of host cells by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Infect Imm. 2003; 71 : 964–972. 12540579

32. Weilinger N.L, Tang P.L., and Thompson R.J. Anoxia-induced NMDA receptor activation opens pannexin channels via Src family kinases. J. Neurosci. 2012; 36 : 12579–12588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1267-12.2012 22956847

33. Iglesias R., Locovei S., Roque A., Alberto A.P., Dahl G., Spray D.C., et al. P2X7 receptor-Pannexin1 complex: pharmacology and signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol, 2008; 295: C752–C760. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2008 18596211

34. Hellberg A., Nowak N., Leippe M., Tannich E., and Bruchhaus I. Recombinant expression and purification of an enzymatically active cysteine proteinase of the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Protein Expr. Purif. 2002; 24 : 131–137. 11812234

35. Nowak N., Lotter H., Tannich E., and Bruchhaus I. Resistance of Entamoeba histolytica to the cysteine proteinase inhibitor E64 is associated with secretion of pro-enzymes and reduced pathogenicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004; 279 : 38260–38266. 15215238

36. Kissoon-Singh V., Moreau F., Tusevych E., and Chadee K. Entamoeba histolytica exacerbates epithelial tight junction permeability and proinflammatory responses in Muc2(-/-) mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2013; 182 : 852–865. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.035 23357502

37. Tillack M., Nowak N., Lotter H., Bracha R., Mirelman D., Tannich E., Bruchhaus I. Increased expression of the major cysteine proteinases by stable episomal transfection underlines the important role of EhCP5 for the pathogenicity of Entamoeba histolytica. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2006; 149 : 58–64. 16753229

38. Ankri S., Stolarsky T., Bracha R., Padilla-Vaca F., Mirelman D. Antisense inhibition of expression of cysteine proteinases affects Entamoeba histolytica-induced formation of liver abscess in hamsters. Infect. Immun. 1999; 67 : 421–422. 9864246

39. Zhang Z., Yan L., Wang L., Seydel K.B., Li E., Ankri S., Mirelman D., Stanley S.L. Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteinases with interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme (ICE) activity cause intestinal inflammation and tissue damage in amoebiasis. Mol. Microbiol. 2000; 37 : 542–548. 10931347

40. Dustin M.L., and Groves J.T. Receptor signaling clusters at immune synapses. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2012; 41 : 543–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155238 22404679

41. Goodridge H., Reyes C.N., Becker C.A., Katsumoto T.R., Ma J., Wolf A.J., et al. Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse.’ Nature. 2011; 472 : 471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature10071 21525931

42. Schenk U., Westendorf A.M., Radaelli E., Casati A., Ferro M., Fumagalli M., et al. Purinergic control of T cell activation by ATP released through Pannexin-1 Hemichannels. Sci. Signal. 2008; 1 : 1–13. doi: 10.1126/stke.112pt1 18364512

43. Woehrle T., Yip L., Elkhal A., Sumi Y., Chen Y., Yao Y., et al. Pannexin-1 hemichannel-mediated ATP release together with P2X1 and P2X4 receptors regulate T-cell activation at the immune synapse. Blood. 2010; 116 : 3475–3484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277707 20660288

44. Jun K., Lee S., Lee H., and Choi B. Integrin a5b1 activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by direct interaction with a bacterial surface protein. Immunity. 2012 : 36 : 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.001 22284412

45. Diamond L.S., Harlow D.R., and Cunnick C.C. A new medium for the axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1978; 72 : 431–432. 212851

46. Denis M., and Chadee K. Cytokine activation of murine macrophages for in vitro killing of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. Infect. Immun. 1989; 57 : 1750–1756. 2542164

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Neutrophil-Derived MMP-8 Drives AMPK-Dependent Matrix Destruction in Human Pulmonary TuberculosisČlánek Circumventing . Virulence by Early Recruitment of Neutrophils to the Lungs during Pneumonic PlagueČlánek Admixture in Humans of Two Divergent Populations Associated with Different Macaque Host SpeciesČlánek Human and Murine Clonal CD8+ T Cell Expansions Arise during Tuberculosis Because of TCR SelectionČlánek Selective Recruitment of Nuclear Factors to Productively Replicating Herpes Simplex Virus GenomesČlánek Fob1 and Fob2 Proteins Are Virulence Determinants of via Facilitating Iron Uptake from FerrioxamineČlánek Remembering MumpsČlánek Human Cytomegalovirus miR-UL112-3p Targets TLR2 and Modulates the TLR2/IRAK1/NFκB Signaling PathwayČlánek Induces the Premature Death of Human Neutrophils through the Action of Its Lipopolysaccharide

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 5- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Parasites and Their Heterophagic Appetite for Disease

- The Elusive Role of the Prion Protein and the Mechanism of Toxicity in Prion Disease

- Intestinal Colonization Dynamics of

- Activation of Typhi-Specific Regulatory T Cells in Typhoid Disease in a Wild-Type . Typhi Challenge Model

- The Engineering of a Novel Ligand in gH Confers to HSV an Expanded Tropism Independent of gD Activation by Its Receptors

- Neutrophil-Derived MMP-8 Drives AMPK-Dependent Matrix Destruction in Human Pulmonary Tuberculosis

- Group Selection and Contribution of Minority Variants during Virus Adaptation Determines Virus Fitness and Phenotype

- Phosphatidic Acid Produced by Phospholipase D Promotes RNA Replication of a Plant RNA Virus

- A Ribonucleoprotein Complex Protects the Interleukin-6 mRNA from Degradation by Distinct Herpesviral Endonucleases

- Characterization of Transcriptional Responses to Different Aphid Species Reveals Genes that Contribute to Host Susceptibility and Non-host Resistance

- Circumventing . Virulence by Early Recruitment of Neutrophils to the Lungs during Pneumonic Plague

- Natural Killer Cell Sensing of Infected Cells Compensates for MyD88 Deficiency but Not IFN-I Activity in Resistance to Mouse Cytomegalovirus

- Manipulation of the Xanthophyll Cycle Increases Plant Susceptibility to

- Ly6C Monocytes Regulate Parasite-Induced Liver Inflammation by Inducing the Differentiation of Pathogenic Ly6C Monocytes into Macrophages

- Admixture in Humans of Two Divergent Populations Associated with Different Macaque Host Species

- Expression in the Fat Body Is Required in the Defense Against Parasitic Wasps in

- Experimental Evolution of an RNA Virus in Wild Birds: Evidence for Host-Dependent Impacts on Population Structure and Competitive Fitness

- Inhibition and Reversal of Microbial Attachment by an Antibody with Parasteric Activity against the FimH Adhesin of Uropathogenic .

- The EBNA-2 N-Terminal Transactivation Domain Folds into a Dimeric Structure Required for Target Gene Activation

- Human and Murine Clonal CD8+ T Cell Expansions Arise during Tuberculosis Because of TCR Selection

- The NLRP3 Inflammasome Is a Pathogen Sensor for Invasive via Activation of α5β1 Integrin at the Macrophage-Amebae Intercellular Junction

- Sequential Conformational Changes in the Morbillivirus Attachment Protein Initiate the Membrane Fusion Process