-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

An Overview of Respiratory Syncytial Virus

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004016

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004016Summary

article has not abstract

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) and Child Health

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), a member of the Paramyxoviridae family, is the leading cause of lower respiratory tract illness (LRI) in infants. From 1993 to 2008, the total RSV hospitalization rate in the United States across all age groups was 55 per 100,000 person-years, slightly lower than the rate of 64 per 100,000 person-years for influenza viruses [1]. In infants, the hospitalization rate was 2,345 per 100,000 person-years for RSV compared to 151 for influenza, consistent with reports that RSV hospitalizes 1–2% of infants in the US each winter, a staggering statistic [1]. RSV disease is not limited to infants. RSV resulted in more hospitalizations in 1–4-year-olds than influenza [1]. One in 13 children under the age of five in the US required medical attention for RSV each year, and 60% of office visits were for 2–5-year-olds [2].

RSV remains a significant cause of death. Over all age groups, influenza caused three times as many deaths as RSV in the US from 1990 to 1999, mostly in the elderly [3]. RSV caused 137 deaths per year in the US in children less than 4 years old, compared to 38 per year in this age group for influenza [3]. Globally, RSV was estimated to have caused 66,000 to 199,000 pneumonia deaths in children less than 5 years old in 2005, making RSV the third most important cause of deadly childhood pneumonia after Streptococcus pneumonia and Haemophilus influenza [4]. RSV is increasingly recognized as a global health priority.

Other than ribavirin, there are no licensed RSV vaccines or therapeutics. The monoclonal antibody (mAb) palivizumab is a neutralizing mAb against a conserved epitope in the viral fusion (F) surface glycoprotein. Palivizumab is administered prophylactically to high-risk infants, such as those with chronic lung disease of prematurity, congenital heart disease, or premature birth at less than 36 weeks gestational age, but it costs $4,500 per patient treatment course [5].

RSV Pathogenesis

RSV apically infects ciliated epithelial cells of the airways. RSV bronchiolitis is characterized by mucus in the airways, sloughed epithelial cell debris, and abundant neutrophils. Airway mucus is a hallmark of RSV LRI, contributing to pulmonary obstruction, but mechanisms of RSV-induced mucus expression remain unclear. RSV-induced mucus is a particular problem in the small diameter airways of premature infants.

Mice are semipermissive for RSV replication. Though more permissive than other inbred mouse strains, BALB/c mice infected with commonly used laboratory RSV strains (e.g., A2 or Long strains) do not exhibit high viral loads or pulmonary mucus. Mouse models, though mechanistic, likely overestimate immune-mediated pathology in RSV pathogenesis. The picture from infants is that fatal RSV LRI is a virus-induced pathology, not an exaggerated immune-mediated pathology [6]. Cotton rats are more permissive and exhibit more RSV antigen in the airway epithelium than mice, but cotton rats also lack lung pathology characteristic of RSV disease.

Our laboratory developed RSV strains that are relatively more pathogenic than commonly used laboratory RSV strains in mice and recapitulate airway mucus and respiratory compromise. We generated a recombinant, strain-chimeric RSV strain, A2-line19F, which expresses the F gene of the mucus-inducing line 19 RSV strain in the genetic background of the laboratory A2 strain [7]. A2-line19F induces airway mucus and exhibits higher viral load in mice than laboratory strains, implicating RSV F in mucus induction [7]–[9]. Breathing difficulty (retractions and nasal flaring) is a symptom of RSV bronchiolitis. One way to quantify breathing effort is to measure pulsus paradoxus, the distension of arteries in the periphery due to breathing effort. RSV A2-line19F and the clinical isolate RSV 2–20 increased breathing effort in mice [8], [10].

RSV Immunity

Immunity to natural RSV infection is partial but protective. Symptomatic RSV reinfection in early childhood is common. Homologous RSV strains can reinfect persons of all ages; thus, sterilizing immunity is not established. However, repeat infections are associated with decreased risk of LRI even if the secondary infection occurs in the first year of life [11]. Thus, in contrast to the lack of solid immunity to RSV upper respiratory tract illness (URI), protective immunity to RSV LRI builds rapidly. This provides rationale for RSV vaccines in the target population aimed at preventing disease. In one study, 64% of infants younger than 9 months old developed neutralizing antibodies (nAb) after primary RSV infection [12].

T cells are important for RSV clearance. In infants, CD8 T cells in the airways correlate with recovery, not disease [13]. In mice, protective versus pathologic roles of T cells depend on the model system. CD8 T cells are critical for RSV clearance, can mediate weight loss and lung lymphocytic inflammation in primary infection, and protect against immunopathology associated with failed vaccines. Vaccine-elicited CD8 T cells can protect against RSV challenge and against RSV A2-line19F-induced mucin expression [9].

A good correlate of protection for RSV is nAbs (mucosal IgA and serum IgG via transudation). There is one serotype of RSV and two antigenic groups, A and B. RSV A is more prevalent and slightly more pathogenic than RSV B. Seroconversion rates (based on neutralization) were reported to be highly group-specific, so a bivalent vaccine may be optimal [14]. Nevertheless, the RSV F protein is relatively conserved (Figure 1), and some anti-F neutralizing mAbs such as palivizumab can protect against A and B strains.

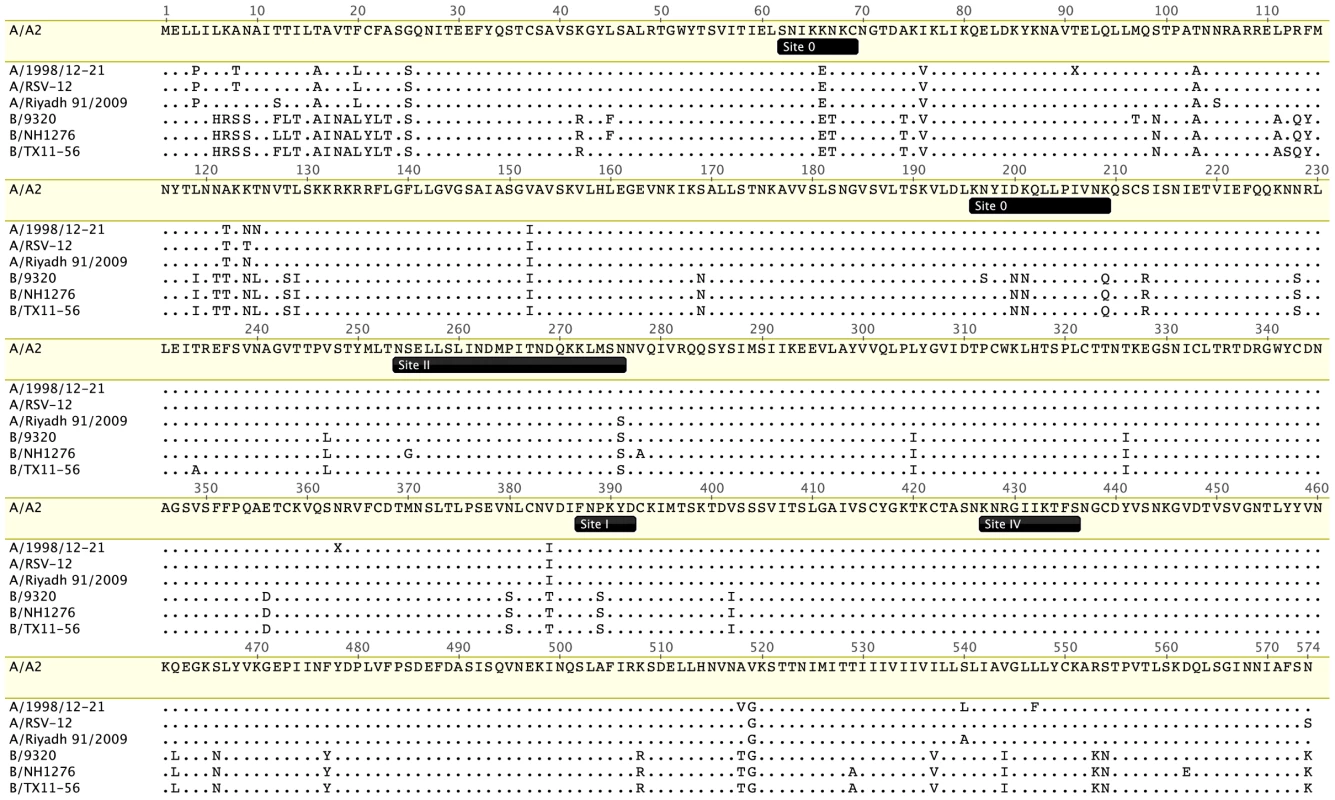

Fig. 1. Conservation of RSV F protein antigenic sites characterized to date.

Four antigenic group A and three group B RSV F protein sequences were aligned using ClustalW and visualized with Geneious Pro software. The RSV A2 F (Genbank protein accession ACO83301) serves as the reference strain. The other representative strains are A/1998/12-21 (Nashville, Tennessee, US, accession AFM95385), A/RSV-12 (Denver, Colorado, US, 2004–2005, accession AEO45929), A/Riyadh/2009 (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, accession AEO23052), B/9320 (Massachusetts, US, 1977, accession AAR14266), B/NH1276 (New Haven, Connecticut, US, 2002, accession AFD34264), and B/TX11-56 (Dallas, Texas, US, 2011, accession AFD34265). Positions of antigenic sites 0, I, II, and IV are from reference [15]. Known nAbs to RSV are specific for either F or the attachment (G) glycoprotein. RSV G is heavily glycosylated and antigenically heterogeneous. Anti-G mAbs are generally less neutralizing in vitro than anti-F mAbs, so F is the preferred vaccine antigen. RSV F and G are both important targets for in vivo neutralization, with F playing a somewhat greater role based on studies in experimental animals. Like F proteins of model paramyxoviruses, RSV F undergoes a conformational change from a prefusion to a postfusion form. Unlike model paramyxoviruses, the RSV attachment glycoprotein is not required for F triggering or virus replication in vitro. Recently, prefusion and postfusion structures of RSV F were solved [15]. An antigenic site (site 0) specific for prefusion F was localized to the top of the prefusion head. Site 0 is targeted by novel mAbs with higher potency than palivizumab [15], [16]. Prefusion F-specific Abs are prevalent in polyclonal neutralizing antisera [17]. However, antigenic site 0 is less conserved than site II to which palivizumab binds (Figure 1).

RSV Inhibits Host Immune Responses

The RSV nonstructural-1 and -2 (NS1 and NS2) proteins inhibit innate and adaptive immune responses to RSV. NS1 and NS2 have multiple functions. For example, NS1 antagonizes type I interferon, dendritic cell maturation, and T cell responses [18]. NS2 binds RIG-I and potently degrades STAT-2 [19], [20]. RSV G is immunomodulatory by at least two mechanisms. RSV produces a secreted G (sG) form in abundance that serves as an antigen decoy, similar to the Ebola virus secreted glycoprotein [21]. Also, a chemokine motif conserved in G modulates immune responses [8].

RSV Vaccines and Antivirals

The challenges to RSV vaccine development are substantial [22]. In 1969, a formalin-inactivated RSV plus alum adjuvant (FI-RSV) vaccine resulted in severe disease exacerbation upon natural RSV exposure. FI-RSV has fettered RSV vaccine development in the past. The FI-RSV vaccination+RSV challenge-enhanced disease immunopathology phenotype is reproducible across laboratories, animal models, and related viruses in their natural host, such as bovine RSV and pneumonia virus of mice. However, mechanisms of FI-RSV-enhanced disease appear multifactorial and remain to be fully elucidated. F and G subunit vaccines studied early on have a history of disease enhancement, albeit to a lesser extent than FI-RSV. RSV subunit vaccines have never been tested in naïve infants. RSV live attenuated vaccines (LAV) have a good safety record in infants.

In RSV naïve infants, the path is paved for RSV LAVs. The advantages of LAVs for other viruses are well known. RSV was attenuated by classic forward mutagenesis. Using reverse genetics, attenuating mutations were incorporated into RSV in different combinations in attempts to strike a balance between attenuation and immunogenicity. A recent RSV LAV candidate (rA2cp248/404/1030ΔSH) was safe in infants but poorly immunogenic, as measured by serum Ab [23]. The Collins group at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and MedImmune have explored a range of attenuation and immunogenicity in a series of RSV A2 strain mutant LAVs, but the optimal balance has proven elusive. Actually, the total number of RSV mutants published is very low compared to other important viruses, owing in part to the small size of the RSV field and technical challenges of RSV reverse genetics [24]. The achievable RSV attenuation and immunogenicity remains to be fully explored. For example, targeted mutagenesis of RSV virulence genes could enhance immunogenicity. Another issue with RSV LAVs is the genetic instability (reversion) of point mutations derived by classical mutagenesis. Again, novel mutations via reverse genetics may elucidate stable attenuation.

Similar to influenza, tetanus, and pertussis, one strategy to target RSV by vaccination is maternal immunization. There is significant RSV disease in 0–2-month-old infants, who will be difficult to protect by active immunization but could be protected by boosting maternal nAb. Critical issues are the half-life of the transferred Ab, estimated to be 1 month, the timing (3rd trimester) of immunization, and insufficient Ab transfer in the case of premature birth.

Antivirals are being developed against RSV. One example is a RSV nucleoside analog against the viral polymerase (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01906164). One paradigm is that usefulness of antivirals for RSV in infants will be limited because viral load has peaked by the time of hospitalization. However, in a careful study of RSV clearance in hospitalized children less than 2 years of age, viral load on day 3 of hospitalization was associated with requirement for intensive care and respiratory failure, spotlighting a potential therapeutic window in the hospitalized infant population [25]. In addition to therapies, there is a need for development of cost-effective prophylaxis agents (e.g., novel mAbs and/or antiviral drugs) beyond palivizumab.

Zdroje

1. ZhouH, ThompsonWW, ViboudCG, RingholzCM, ChengPY, et al. (2012) Hospitalizations associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States, 1993–2008. Clin Infect Dis 54 : 1427–1436.

2. HallCB, WeinbergGA, IwaneMK, BlumkinAK, EdwardsKM, et al. (2009) The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med 360 : 588–598.

3. ThompsonWW, ShayDK, WeintraubE, BrammerL, CoxN, et al. (2003) Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 289 : 179–186.

4. NairH, NokesDJ, GessnerBD, DheraniM, MadhiSA, et al. (2010) Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 375 : 1545–1555.

5. MahadeviaPJ, MasaquelAS, PolakMJ, WeinerLB (2012) Cost utility of palivizumab prophylaxis among pre-term infants in the United States: a national policy perspective. J Med Econ 15 : 987–996.

6. WelliverTP, GarofaloRP, HosakoteY, HintzKH, AvendanoL, et al. (2007) Severe human lower respiratory tract illness caused by respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus is characterized by the absence of pulmonary cytotoxic lymphocyte responses. J Infect Dis 195 : 1126–1136.

7. MooreML, ChiMH, LuongoC, LukacsNW, PolosukhinVV, et al. (2009) A chimeric A2 strain of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) with the fusion protein of RSV strain line 19 exhibits enhanced viral load, mucus, and airway dysfunction. J Virol 83 : 4185–4194.

8. Boyoglu-BarnumS, GastonKA, ToddSO, BoyogluC, ChirkovaT, et al. (2013) A respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) anti-G protein F(ab′)2 monoclonal antibody suppresses mucous production and breathing effort in RSV rA2-line19F-infected Balb/c mice. J Virol 87 : 10955–10967.

9. LeeS, StokesKL, CurrierMG, SakamotoK, LukacsNW, et al. (2012) Vaccine-Elicited CD8+ T Cells Protect against Respiratory Syncytial Virus Strain A2-Line19F-Induced Pathogenesis in BALB/c Mice. J Virol 86 : 13016–13024.

10. StokesKL, ChiMH, SakamotoK, NewcombDC, CurrierMG, et al. (2011) Differential pathogenesis of respiratory syncytial virus clinical isolates in BALB/c mice. J Virol 85 : 5782–5793.

11. OhumaEO, OkiroEA, OcholaR, SandeCJ, CanePA, et al. (2012) The natural history of respiratory syncytial virus in a birth cohort: the influence of age and previous infection on reinfection and disease. Am J Epidemiol 176 : 794–802.

12. WrightPF, GruberWC, PetersM, ReedG, ZhuY, et al. (2002) Illness severity, viral shedding, and antibody responses in infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis caused by respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis 185 : 1011–1018.

13. LukensMV, van de PolAC, CoenjaertsFE, JansenNJ, KampVM, et al. (2010) A systemic neutrophil response precedes robust CD8(+) T-cell activation during natural respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants. J Virol 84 : 2374–2383.

14. SandeCJ, MutungaMN, MedleyGF, CanePA, NokesDJ (2013) Group - and genotype-specific neutralizing antibody responses against respiratory syncytial virus in infants and young children with severe pneumonia. J Infect Dis 207 : 489–492.

15. McLellanJS, ChenM, LeungS, GraepelKW, DuX, et al. (2013) Structure of RSV Fusion Glycoprotein Trimer Bound to a Prefusion-Specific Neutralizing Antibody. Science 340 : 1113–1117.

16. CortiD, BianchiS, VanzettaF, MinolaA, PerezL, et al. (2013) Cross-neutralization of four paramyxoviruses by a human monoclonal antibody. Nature 501 : 439–443.

17. MagroM, MasV, ChappellK, VazquezM, CanoO, et al. (2012) Neutralizing antibodies against the preactive form of respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein offer unique possibilities for clinical intervention. PNAS 109 : 3089–3094.

18. MunirS, HillyerP, Le NouenC, BuchholzUJ, RabinRL, et al. (2011) Respiratory syncytial virus interferon antagonist NS1 protein suppresses and skews the human T lymphocyte response. PLoS Pathog 7: e1001336.

19. LingZ, TranKC, TengMN (2009) Human respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural protein NS2 antagonizes the activation of beta interferon transcription by interacting with RIG-I. J Virol 83 : 3734–3742.

20. RamaswamyM, ShiL, VargaSM, BarikS, BehlkeMA, et al. (2006) Respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural protein 2 specifically inhibits type I interferon signal transduction. Virology 344 : 328–339.

21. BukreyevA, YangL, CollinsPL (2012) The secreted G protein of human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) antagonizes antibody-mediated restriction of replication involving macrophages and complement. J Virol 86 : 10880–10884.

22. GrahamBS (2011) Biological challenges and technological opportunities for respiratory syncytial virus vaccine development. Immunol Rev 239 : 149–166.

23. KarronRA, WrightPF, BelsheRB, ThumarB, CaseyR, et al. (2005) Identification of a recombinant live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate that is highly attenuated in infants. J Infect Dis 191 : 1093–1104.

24. HotardAL, ShaikhFY, LeeS, YanD, TengMN, et al. (2012) A stabilized respiratory syncytial virus reverse genetics system amenable to recombination-mediated mutagenesis. Virology 434 : 129–136.

25. El SaleebyCM, BushAJ, HarrisonLM, AitkenJA, DevincenzoJP (2011) Respiratory syncytial virus load, viral dynamics, and disease severity in previously healthy naturally infected children. J Infect Dis 204 : 996–1002.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Affinity Proteomics Reveals Elevated Muscle Proteins in Plasma of Children with Cerebral MalariaČlánek The Transcriptional Activator LdtR from ‘ Liberibacter asiaticus’ Mediates Osmotic Stress ToleranceČlánek Complement-Related Proteins Control the Flavivirus Infection of by Inducing Antimicrobial PeptidesČlánek Fungal Chitin Dampens Inflammation through IL-10 Induction Mediated by NOD2 and TLR9 ActivationČlánek Parasite Fate and Involvement of Infected Cells in the Induction of CD4 and CD8 T Cell Responses to

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 4- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- , , , Genetic Variability: Cryptic Biological Species or Clonal Near-Clades?

- Early Mortality Syndrome Outbreaks: A Microbial Management Issue in Shrimp Farming?

- Wormholes in Host Defense: How Helminths Manipulate Host Tissues to Survive and Reproduce

- Plastic Proteins and Monkey Blocks: How Lentiviruses Evolved to Replicate in the Presence of Primate Restriction Factors

- The 2010 Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: How Science Solved a Controversy

- Affinity Proteomics Reveals Elevated Muscle Proteins in Plasma of Children with Cerebral Malaria

- Noncanonical Role for the Host Vps4 AAA+ ATPase ESCRT Protein in the Formation of Replicase

- Efficient Parvovirus Replication Requires CRL4-Targeted Depletion of p21 to Prevent Its Inhibitory Interaction with PCNA

- Host-to-Pathogen Gene Transfer Facilitated Infection of Insects by a Pathogenic Fungus

- The Transcriptional Activator LdtR from ‘ Liberibacter asiaticus’ Mediates Osmotic Stress Tolerance

- Coxsackievirus B Exits the Host Cell in Shed Microvesicles Displaying Autophagosomal Markers

- TCR Affinity Associated with Functional Differences between Dominant and Subdominant SIV Epitope-Specific CD8 T Cells in Rhesus Monkeys

- Coxsackievirus-Induced miR-21 Disrupts Cardiomyocyte Interactions via the Downregulation of Intercalated Disk Components

- Ligands of MDA5 and RIG-I in Measles Virus-Infected Cells

- Kind Discrimination and Competitive Exclusion Mediated by Contact-Dependent Growth Inhibition Systems Shape Biofilm Community Structure

- Structural Differences Explain Diverse Functions of Actins

- HSCARG Negatively Regulates the Cellular Antiviral RIG-I Like Receptor Signaling Pathway by Inhibiting TRAF3 Ubiquitination Recruiting OTUB1

- Vaginitis: When Opportunism Knocks, the Host Responds

- Complement-Related Proteins Control the Flavivirus Infection of by Inducing Antimicrobial Peptides

- Fungal Chitin Dampens Inflammation through IL-10 Induction Mediated by NOD2 and TLR9 Activation

- Microbial Pathogens Trigger Host DNA Double-Strand Breaks Whose Abundance Is Reduced by Plant Defense Responses

- Alveolar Macrophages Are Essential for Protection from Respiratory Failure and Associated Morbidity following Influenza Virus Infection

- An Interaction between Glutathione and the Capsid Is Required for the Morphogenesis of C-Cluster Enteroviruses

- Concerted Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Imported DNA and ComE DNA Uptake Protein during Gonococcal Transformation

- Potent Dengue Virus Neutralization by a Therapeutic Antibody with Low Monovalent Affinity Requires Bivalent Engagement

- Regulation of Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type I Latency and Reactivation by HBZ and Rex

- Functionally Redundant RXLR Effectors from Act at Different Steps to Suppress Early flg22-Triggered Immunity

- The Pathogenic Mechanism of the Virulence Factor, Mycolactone, Depends on Blockade of Protein Translocation into the ER

- Role of Calmodulin-Calmodulin Kinase II, cAMP/Protein Kinase A and ERK 1/2 on -Induced Apoptosis of Head Kidney Macrophages

- An Overview of Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- First Experimental Model of Enhanced Dengue Disease Severity through Maternally Acquired Heterotypic Dengue Antibodies

- Binding of Glutathione to Enterovirus Capsids Is Essential for Virion Morphogenesis

- IFITM3 Restricts Influenza A Virus Entry by Blocking the Formation of Fusion Pores following Virus-Endosome Hemifusion

- Parasite Fate and Involvement of Infected Cells in the Induction of CD4 and CD8 T Cell Responses to

- Deficient IFN Signaling by Myeloid Cells Leads to MAVS-Dependent Virus-Induced Sepsis

- Pernicious Pathogens or Expedient Elements of Inheritance: The Significance of Yeast Prions

- The HMW1C-Like Glycosyltransferases—An Enzyme Family with a Sweet Tooth for Simple Sugars

- The Expanding Functions of Cellular Helicases: The Tombusvirus RNA Replication Enhancer Co-opts the Plant eIF4AIII-Like AtRH2 and the DDX5-Like AtRH5 DEAD-Box RNA Helicases to Promote Viral Asymmetric RNA Replication

- Mining Herbaria for Plant Pathogen Genomes: Back to the Future

- Inferring Influenza Infection Attack Rate from Seroprevalence Data

- A Human Lung Xenograft Mouse Model of Nipah Virus Infection

- Mast Cells Expedite Control of Pulmonary Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection by Enhancing the Recruitment of Protective CD8 T Cells to the Lungs

- Cytosolic Peroxidases Protect the Lysosome of Bloodstream African Trypanosomes from Iron-Mediated Membrane Damage

- Abortive T Follicular Helper Development Is Associated with a Defective Humoral Response in -Infected Macaques

- JC Polyomavirus Infection Is Strongly Controlled by Human Leucocyte Antigen Class II Variants

- Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides Promote Microbial Mutagenesis and Pathoadaptation in Chronic Infections

- Estimating the Fitness Advantage Conferred by Permissive Neuraminidase Mutations in Recent Oseltamivir-Resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 Influenza Viruses

- Progressive Accumulation of Activated ERK2 within Highly Stable ORF45-Containing Nuclear Complexes Promotes Lytic Gammaherpesvirus Infection

- Caspase-1-Like Regulation of the proPO-System and Role of ppA and Caspase-1-Like Cleaved Peptides from proPO in Innate Immunity

- Is Required for High Efficiency Viral Replication

- Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Triggers Type I IFN Production in Murine Conventional Dendritic Cells via a cGAS/STING-Mediated Cytosolic DNA-Sensing Pathway

- Evidence That Bank Vole PrP Is a Universal Acceptor for Prions

- Rapid Response to Selection, Competitive Release and Increased Transmission Potential of Artesunate-Selected Malaria Parasites

- Inactivation of Genes for Antigenic Variation in the Relapsing Fever Spirochete Reduces Infectivity in Mice and Transmission by Ticks

- Exposure-Dependent Control of Malaria-Induced Inflammation in Children

- A Neutralizing Anti-gH/gL Monoclonal Antibody Is Protective in the Guinea Pig Model of Congenital CMV Infection

- The Apical Complex Provides a Regulated Gateway for Secretion of Invasion Factors in

- A Highly Conserved Haplotype Directs Resistance to Toxoplasmosis and Its Associated Caspase-1 Dependent Killing of Parasite and Host Macrophage

- A Quantitative High-Resolution Genetic Profile Rapidly Identifies Sequence Determinants of Hepatitis C Viral Fitness and Drug Sensitivity

- Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Romidepsin Induces HIV Expression in CD4 T Cells from Patients on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy at Concentrations Achieved by Clinical Dosing

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The 2010 Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: How Science Solved a Controversy

- , , , Genetic Variability: Cryptic Biological Species or Clonal Near-Clades?

- Efficient Parvovirus Replication Requires CRL4-Targeted Depletion of p21 to Prevent Its Inhibitory Interaction with PCNA

- An Overview of Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání