-

Články

Reklama

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

ReklamaThe HMW1C-Like Glycosyltransferases—An Enzyme Family with a Sweet Tooth for Simple Sugars

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003977

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003977Summary

article has not abstract

The HMW1/HMW2 Two-Partner Secretion Systems Have a Third Partner

The HMW1 and HMW2 adhesins of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae are high-molecular weight proteins that are secreted by the two-partner secretion (TPS) pathway, also known as the Type Vb secretion pathway [1], [2]. TPS systems typically consist of a large extracellular protein called a TpsA protein (encoded by a tpsA gene) and a cognate outer membrane pore-forming translocator protein called a TpsB protein (encoded by a tpsB gene). HMW1 and HMW2 are TpsA proteins and are encoded by hmw1A and hmw2A, respectively, and HMW1B and HMW2B are the cognate TpsB proteins and are encoded by hmw1B and hmw2B, respectively [3], [4]. The hmw1A-hmw1B and hmw2A-hmw2B gene clusters have a similar configuration and are located in physically separate regions of the H. influenzae chromosome.

A distinctive feature of the HMW1 and HMW2 systems is the presence of a third protein, called HMW1C in the HMW1 system and HMW2C in the HMW2 system. HMW1C and HMW2C are highly homologous glycosyltransferases [5], [6] that are responsible for adding sugar moieties to HMW1 and HMW2 and are encoded by the hmw1C and hmw2C genes, located downstream of hmw1B and hmw2B, respectively. Since the HMW1 and HMW2 systems have similar properties [7], in this review we will confine our discussion to the HMW1 system.

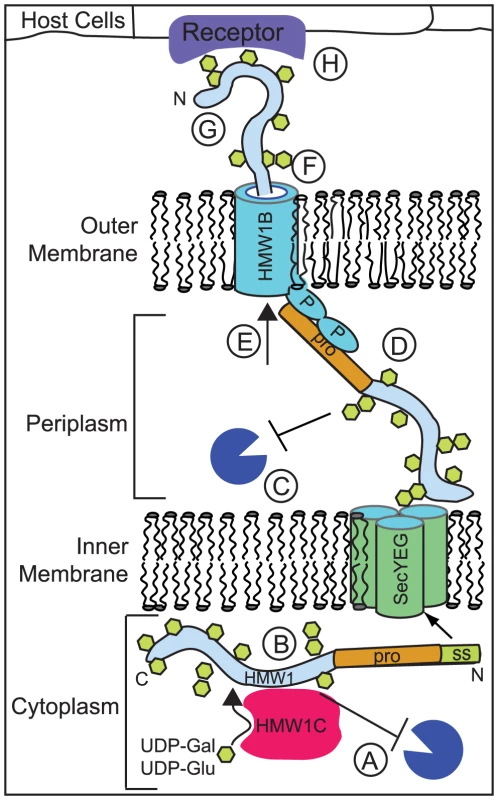

The HMW1 adhesin is presented on the bacterial surface via a multistep process that requires HMW1C-mediated glycosylation (reviewed in [8]). As shown schematically in Figure 1, HMW1 is synthesized and glycosylated in the cytoplasm and is directed to the Sec translocase in the inner membrane via an extended N-terminal signal sequence [9]. The signal sequence is cleaved by signal peptidase I, and nascent HMW1 is then directed to its cognate HMW1B β-barrel pore in the outer membrane [9]. The initial interaction between HMW1 and HMW1B occurs via the N-terminal TPS secretion domain in the HMW1 pro-piece and the periplasmic domain in HMW1B [10]. The HMW1 pro-piece spans amino acids 69–441 and is cleaved during or following secretion through the HMW1B pore [9]. HMW1 is ultimately tethered to the bacterial surface via a noncovalent interaction that requires the C-terminal 20 amino acids of the protein and is dependent upon disulfide bond formation between two conserved cysteine residues in this region (cysteines 1518 and 1528). Immunolabeling studies have demonstrated that the immediate C terminus of HMW1 is inaccessible to surface labeling, suggesting that it remains in the periplasm or is buried in the HMW1B pore [5], [11]. Elimination of HMW1C results in degradation of HMW1 in bacterial lysates, indicating that glycosylation is required for HMW1 stability. Any remaining nonglycosylated HMW1 is released into the culture supernatant, indicating that glycosylation is also required for HMW1 tethering to the bacterial surface [5].

Fig. 1. Glycosylation by HMW1C may play several roles in promoting HMW1 stability, export, folding, and function.

HMW1C has the potential to contribute to several different processes that occur during HMW1 synthesis and transit across the inner and outer membranes. First of all, HMW1C glycosylates the HMW1 adhesin in the cytoplasm and is likely to be involved in the stability of the HMW1 adhesin during or after its synthesis. Glycosylation may contribute to stability of HMW1 in the (A) cytoplasm or (C) periplasm [5], [7]. Alternatively, the HMW1C protein may improve stability of HMW1 by acting as a (B) chaperone prior to secretion of the adhesin. It is unlikely that the activity of HMW1C is required for export of the adhesin across either the inner or outer membrane, as fully processed HMW1 is found in the supernatant in the absence of HMW1C [5]. It is unclear whether glycosylation influences interaction of HMW1 with the (D) HMW1B periplasmic domain prior to transit, (E) the HMW1B pore during transit, or (F) the docking region of HMW1B upon surface tethering [5], [11]. It is also unclear whether glycosylation participates in (G) protein folding upon export. Evidence from the nonglycosylated Bordetella prototypic, two-partner, secreted adhesin FHA indicates that this adhesin remains unfolded in the cytoplasm and folds very rapidly upon export via its TpsB secretion pore [30]. One hypothesis is that the energy generated by this rapid folding is at least part of what drives export of TpsA proteins across the outer membrane [2]. Finally, glycosylation of HMW1 may be required for (H) adherence to host cells or host interaction in a particular niche. Manual analysis of mass spectra of HMW1 was required to recognize that glycan structures are present at asparagine residues in conserved NXS/T motifs, reflecting the fact that the modifying carbohydrates are mono-hexose or di-hexose groups rather than complex polysaccharides [12], [13]. There are at least 31 residues that are modified with glucose, galactose, glucose-glucose, or glucose-galactose residues in the mature surface-localized HMW1 protein [12], [13]. Based on biochemical analysis and examination of the crystal structure of the HMW1 pro-piece, the pro-piece is nonglycosylated, perhaps because glycosylation would interfere with cleavage of this fragment, which occurs by an undefined mechanism (Figure 1) [9], [12], [14].

HMW1C Is the Prototype Member of a New Subfamily of Glycosyltransferases

Protein glycosylation occurs in all kingdoms of life and is thought to influence protein folding, stability, and function [15], [16]. Some bacteria produce complex O-linked or N-linked glycosyltransferase systems. These systems have been studied in pathogenic bacteria and glycosylate proteins that are typically surface exposed, suggesting a role for glycosylation in bacteria–host interactions [17]. However, none of the previously studied bacterial glycosyltransferase pathways operates like HMW1C, which is capable by itself of forming both N-linked carbohydrate bonds to the HMW1 polypeptide and O-glycosidic bonds between hexose sugars [12], [18], [19].

Based on homology analysis and molecular modeling, HMW1C belongs to the GT41 family of glycosyltransferases, a family that otherwise contains O-GlcNAc transferases. HMW1C consists of three discrete domains, including an α-helical AAD domain at the N terminus and two Rossman-like domains that create a GT-B fold at the C terminus. Interestingly, the AAD fold in HMW1C differs from the so-called tetratricopeptide repeats (TPR) fold that is characteristic of the GT41 family, and the contacts between the AAD domain and the GT-B domain in HMW1C create a unique groove that is absent in other known members of the GT41 family. Thus, the HMW1C protein represents a novel glycosyltransferase subfamily [13].

Among the best-described bacterial N-linked glycosyltransferase systems is the Pgl system in Campylobacter jejuni [20]–[22]. While both the Pgl system and HMW1C affix sugars to their target proteins at asparagines, the similarities end there. First, the Pgl system consists of at least ten proteins encoded by a gene cluster [23], rather than a single protein like HMW1C. Second, the Pgl enzymes are active in the periplasm, while HMW1C acts in the cytoplasm [5]. Third, the Pgl enzymes add a heptasaccharide that is most likely formed in the cytoplasm on a lipid carrier that is then flipped into the periplasm. In contrast, HMW1C adds single UDP-linked sugars to HMW1 without the contribution of a lipid carrier [12].

The HMW1C-Like Glycosyltransferases Segregate into Two Subsets

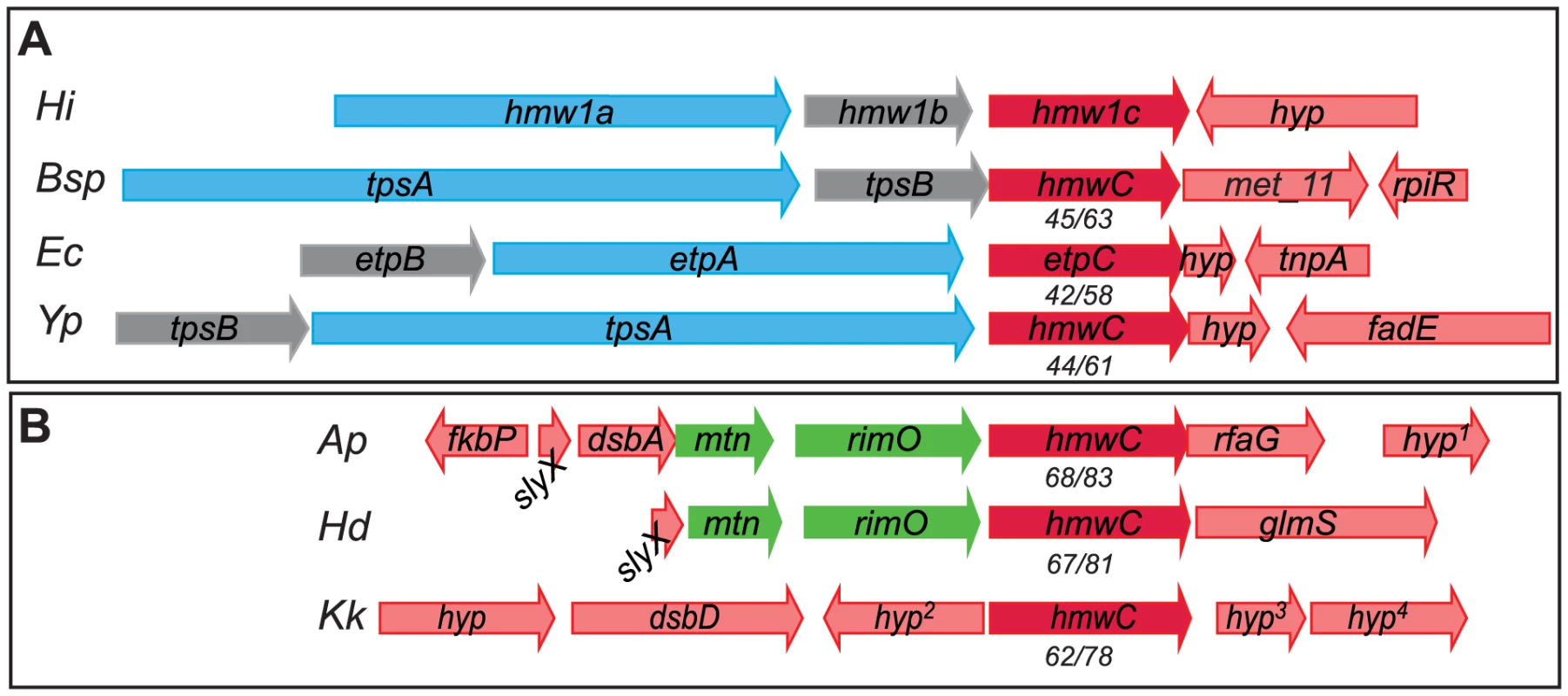

Based on homology analysis of predicted amino acid sequences, HMW1C-like proteins are prevalent among bacteria in the Pastuereallaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Neisseriaceae, and Burkholderiaceae families and appear to segregate into two categories [24]. The first category contains enzymes encoded by genes adjacent to predicted tpsA and tpsB genes in apparent TPS systems (Figure 2A). Examples of HMW1C-like proteins that fall into this category are EtpC in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) [25], RscC in Yersinia enterocolitica [26], and predicted HMW1C-like glycosyltransferases in Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Burkholderia spp. Among these proteins, only EtpC has been demonstrated to possess glycosyltransferase activity, adding sugar residues to the target EtpA adhesin [25]. In fact, glycosylation of EtpA appears to affect adhesin interaction with host cells, as nonglycosylated EtpA is less adherent to Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells but hyperadherent to HCT-8 intestinal cells when compared to glycosylated EtpA [25]. By analogy to the HMW1 system and the Etp system, we hypothesize that the HMW1C-like enzymes in this category modify the co-produced TpsA protein.

Fig. 2. HMW1C-like proteins in two categories: Those encoded by loci that contain obvious substrate genes and those encoded by isolated genes without adjacent substrate genes.

Numbers below hmw1C-like genes represent translated protein sequence percent identity/similarity when compared to H. influenzae HMW1C. (A) HMW1C-like enzymes encoded in apparent TPS systems. (B) HMW1C-like enzymes encoded in loci without obvious surface protein targets for glycosylation. Abbreviations: Hi, H. influenzae 86-028NP; Bsp, Burkholderia species GCE1003; Ec, Enterotoxigenic E. coli H10407; Yp, Y. pseudotuberculosis YPIII; Ap, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae L20; Hd, H. ducreyi HD35000; Kk, K. kingae 269–492; hyp, hypothetical with no conserved domains; hyp1, predicted lipoprotein; hyp2, predicted UDP-glcNAc carboxyvinyltransferase; hyp3, predicted 2 C-methyl-D erythritol-4-phosphate cytidyltransferase; hyp4, predicted deoxyguanosinetriphosphate triphosphohydrolase. The second category of HMW1C-like proteins contains enzymes that are encoded by genes adjacent to genes encoding ribosomal proteins and other transferase enzymes involved in carbohydrate modification. Members of this category have no obvious predicted protein target for glycosylation and include the crystallized Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae HMW1C-like protein (ApHMW1C) and predicted HMW1C-like proteins in H. ducreyi and Kingella kingae (Figure 2B). Of the proteins in this category, only ApHMW1C has been characterized and is known to possess glycotransferase activity [18], [19], [27]. Recent work has demonstrated that the ApHMW1C glycosyltransferase preferentially decorates predicted autotransporter proteins as well as other outer membrane proteins when expressed in vivo and in E. coli [27], suggesting that enzymes in this category may generally have a preference for glycosylation of outer membrane proteins. It is interesting to note that the HMW1C-like glycosyltransferases in this second category are more homologous to the prototype HMW1C protein than are the HMW1C-like proteins encoded by TPS loci.

HMW1C-Like Enzymes Have a Well-Defined Structure Involved in Binding and Transferring UDP-Hexoses

The crystal structure of ApHMW1C provides some clues as to how HMW1C-like glycosyltransferases are able to decorate asparagines. When overlaid using structural prediction algorithms, HMW1C and ApHMW1C are nearly identical, differing only by a disordered 30-amino acid N-terminal tail that is present in HMW1C and absent in ApHMW1C [19]. Given this level of identity, predictions about structure-function relationships in ApHMW1C are likely to apply to H. influenzae HMW1C and potentially other HMW1C-like proteins. Consistent with this conclusion, mutation of amino acids in HMW1C corresponding to amino acids that line the likely UDP-hexose binding pocket in ApHMW1C eliminates the ability of HMW1C to glycosylate HMW1 or to produce functional HMW1 when expressed in whole bacteria [19]. Examination of the ApHMW1C structure indicates a funnel-shaped groove immediately adjacent to the predicted UDP-hexose binding pocket. When key residues within this groove are mutated in HMW1C, glycosylation of HMW1 is eliminated, indicating that the groove plays an important role in acceptor protein modification [19]. A complete understanding of the specificity and limitations of the HMW1C-like enzyme family may help in an industrial setting, as a single enzyme able to catalyze the first step of N-linked protein glycosylation without a lipid carrier has potential to become a workhorse for in vitro protein production [28].

What Do We Still Want to Learn About HMW1C-Like Glycosyltransferases?

Despite the relative simplicity of HMW1C-mediated glycosylation, there is still much to learn about how the HMW1C prototype operates and even more to learn about the function and targets of HMW1C homologs in other medically relevant bacteria. First, we do not understand how HMW1C recognizes its target and chooses specific glycosylation sites, as only a subset of NXS/T motifs in HMW1 are decorated based on mass spectrometry analysis. A better understanding of HMW1C target recognition may assist in development of in vitro glycosylation systems for protein manufacture and also increase understanding of protein–protein interactions in bacteria. Second, while it is clear that HMW1C interacts directly with HMW1 [5], the number of HMW1C molecules that bind to HMW1 at any given time and the duration of this interaction in the cytoplasm are still unknown. This information may help to clarify whether HMW1C has both glycosyltransferase activity and chaperone activity to stave off degradation of HMW1 (Figure 1). Third, the glycosylation targets in bacteria that have no co-transcribed tpsA gene alongside the gene that codes for the HMW1C-like enzyme remain to be determined, although progress has been made in identifying potential targets of ApHMW1C [27]. Knowledge of these targets will help to clarify whether there are consensus glycosylation target sequences among HMW1C-like enzymes and whether the cellular location of glycosylation is conserved. Fourth, while it is clear that glycosylation is required for HMW1 tethering to the bacterial surface, the mechanism involved is unknown. Finally, it will also be important to elucidate how HMW1C-mediated glycosylation of target proteins affects bacterial pathogenesis, expanding the limited literature on the role that HMW1C-mediated glycosylation may play in bacteria–host interactions [19], [25], [26], [29].

The HMW1C-like glycosyltransferases have novel features, and advances in our understanding of this interesting group of enzymes will likely have important implications for the field of glycobiology and the field of bacterial pathogenesis.

Zdroje

1. HendersonIR, Navarro-GarciaF, DesvauxM, FernandezRC, Ala'AldeenD (2004) Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68 : 692–744.

2. Jacob-DubuissonF, GuerinJ, BaelenS, ClantinB (2013) Two-partner secretion: as simple as it sounds? Res Microbiol 164 : 583–595.

3. BarenkampSJ, St GemeJW3rd (1994) Genes encoding high-molecular-weight adhesion proteins of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae are part of gene clusters. Infect Immun 62 : 3320–3328.

4. BuscherAZ, BurmeisterK, BarenkampSJ, St GemeJW3rd (2004) Evolutionary and functional relationships among the nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae HMW family of adhesins. J Bacteriol 186 : 4209–4217.

5. GrassS, BuscherAZ, SwordsWE, ApicellaMA, BarenkampSJ, et al. (2003) The Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 adhesin is glycosylated in a process that requires HMW1C and phosphoglucomutase, an enzyme involved in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol 48 : 737–751.

6. BarenkampSJ, LeiningerE (1992) Cloning, expression, and DNA sequence analysis of genes encoding nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae high-molecular-weight surface-exposed proteins related to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 60 : 1302–1313.

7. St GemeJW3rd, GrassS (1998) Secretion of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 and HMW2 adhesins involves a periplasmic intermediate and requires the HMWB and HMWC proteins. Mol Microbiol 27 : 617–630.

8. St GemeJW3rd, YeoHJ (2009) A prototype two-partner secretion pathway: the Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 and HMW2 adhesin systems. Trends Microbiol 17 : 355–360.

9. GrassS, St GemeJW3rd (2000) Maturation and secretion of the non-typable Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 adhesin: roles of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. Mol Microbiol 36 : 55–67.

10. SuranaNK, BuscherAZ, HardyGG, GrassS, Kehl-FieT, et al. (2006) Translocator proteins in the two-partner secretion family have multiple domains. J Biol Chem 281 : 18051–18058.

11. BuscherAZ, GrassS, HeuserJ, RothR, St GemeJW3rd (2006) Surface anchoring of a bacterial adhesin secreted by the two-partner secretion pathway. Mol Microbiol 61 : 470–483.

12. GrassS, LichtiCF, TownsendRR, GrossJ, St GemeJW3rd (2010) The Haemophilus influenzae HMW1C protein is a glycosyltransferase that transfers hexose residues to asparagine sites in the HMW1 adhesin. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000919.

13. GrossJ, GrassS, DavisAE, Gilmore-ErdmannP, TownsendRR, et al. (2008) The Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 adhesin is a glycoprotein with an unusual N-linked carbohydrate modification. J Biol Chem 283 : 26010–26015.

14. YeoHJ, YokoyamaT, WalkiewiczK, KimY, GrassS, et al. (2007) The structure of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 pro-piece reveals a structural domain essential for bacterial two-partner secretion. J Biol Chem 282 : 31076–31084.

15. HeleniusA, AebiM (2001) Intracellular functions of N-linked glycans. Science 291 : 2364–2369.

16. NothaftH, SzymanskiCM (2013) Bacterial protein N-glycosylation: new perspectives and applications. J Biol Chem 288 : 6912–6920.

17. SchmidtMA, RileyLW, BenzI (2003) Sweet new world: glycoproteins in bacterial pathogens. Trends Microbiol 11 : 554–561.

18. ChoiKJ, GrassS, PaekS, St GemeJW3rd, YeoHJ (2010) The Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae HMW1C-like glycosyltransferase mediates N-linked glycosylation of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 adhesin. PLoS One 5: e15888.

19. KawaiF, GrassS, KimY, ChoiKJ, St GemeJW3rd, et al. (2011) Structural insights into the glycosyltransferase activity of the Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae HMW1C-like protein. J Biol Chem 286 : 38546–38557.

20. WackerM, LintonD, HitchenPG, Nita-LazarM, HaslamSM, et al. (2002) N-linked glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni and its functional transfer into E. coli. Science 298 : 1790–1793.

21. SzymanskiCM, YaoR, EwingCP, TrustTJ, GuerryP (1999) Evidence for a system of general protein glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni. Mol Microbiol 32 : 1022–1030.

22. LintonD, AllanE, KarlyshevAV, CronshawAD, WrenBW (2002) Identification of N-acetylgalactosamine-containing glycoproteins PEB3 and CgpA in Campylobacter jejuni.. Mol Microbiol 43 : 497–508.

23. JervisAJ, ButlerJA, LawsonAJ, LangdonR, WrenBW, et al. (2012) Characterization of the structurally diverse N-linked glycans of Campylobacter species. J Bacteriol 194 : 2355–2362.

24. AltschulSF, GishW, MillerW, MyersEW, LipmanDJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215 : 403–410.

25. FleckensteinJM, RoyK, FischerJF, BurkittM (2006) Identification of a two-partner secretion locus of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 74 : 2245–2258.

26. NelsonKM, YoungGM, MillerVL (2001) Identification of a locus involved in systemic dissemination of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun 69 : 6201–6208.

27. NaegeliA, NeupertC, FanYY, LinCW, PoljakK, et al. (2013) Molecular analysis of an alternative N-glycosylation machinery by functional transfer from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae to Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem (2013). In Press, PMID: 24275653.

28. LominoJV, NaegeliA, OrwenyoJ, AminMN, AebiM, et al. (2013) A two-step enzymatic glycosylation of polypeptides with complex N-glycans. Bioorg Med Chem 21 : 2262–2270.

29. RoyK, HamiltonD, AllenKP, RandolphMP, FleckensteinJM (2008) The EtpA exoprotein of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli promotes intestinal colonization and is a protective antigen in an experimental model of murine infection. Infect Immun 76 : 2106–2112.

30. HodakH, ClantinB, WilleryE, VilleretV, LochtC, et al. (2006) Secretion signal of the filamentous haemagglutinin, a model two-partner secretion substrate. Mol Microbiol 61 : 368–382.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Affinity Proteomics Reveals Elevated Muscle Proteins in Plasma of Children with Cerebral MalariaČlánek The Transcriptional Activator LdtR from ‘ Liberibacter asiaticus’ Mediates Osmotic Stress ToleranceČlánek Complement-Related Proteins Control the Flavivirus Infection of by Inducing Antimicrobial PeptidesČlánek Fungal Chitin Dampens Inflammation through IL-10 Induction Mediated by NOD2 and TLR9 ActivationČlánek Parasite Fate and Involvement of Infected Cells in the Induction of CD4 and CD8 T Cell Responses to

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 4- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- , , , Genetic Variability: Cryptic Biological Species or Clonal Near-Clades?

- Early Mortality Syndrome Outbreaks: A Microbial Management Issue in Shrimp Farming?

- Wormholes in Host Defense: How Helminths Manipulate Host Tissues to Survive and Reproduce

- Plastic Proteins and Monkey Blocks: How Lentiviruses Evolved to Replicate in the Presence of Primate Restriction Factors

- The 2010 Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: How Science Solved a Controversy

- Affinity Proteomics Reveals Elevated Muscle Proteins in Plasma of Children with Cerebral Malaria

- Noncanonical Role for the Host Vps4 AAA+ ATPase ESCRT Protein in the Formation of Replicase

- Efficient Parvovirus Replication Requires CRL4-Targeted Depletion of p21 to Prevent Its Inhibitory Interaction with PCNA

- Host-to-Pathogen Gene Transfer Facilitated Infection of Insects by a Pathogenic Fungus

- The Transcriptional Activator LdtR from ‘ Liberibacter asiaticus’ Mediates Osmotic Stress Tolerance

- Coxsackievirus B Exits the Host Cell in Shed Microvesicles Displaying Autophagosomal Markers

- TCR Affinity Associated with Functional Differences between Dominant and Subdominant SIV Epitope-Specific CD8 T Cells in Rhesus Monkeys

- Coxsackievirus-Induced miR-21 Disrupts Cardiomyocyte Interactions via the Downregulation of Intercalated Disk Components

- Ligands of MDA5 and RIG-I in Measles Virus-Infected Cells

- Kind Discrimination and Competitive Exclusion Mediated by Contact-Dependent Growth Inhibition Systems Shape Biofilm Community Structure

- Structural Differences Explain Diverse Functions of Actins

- HSCARG Negatively Regulates the Cellular Antiviral RIG-I Like Receptor Signaling Pathway by Inhibiting TRAF3 Ubiquitination Recruiting OTUB1

- Vaginitis: When Opportunism Knocks, the Host Responds

- Complement-Related Proteins Control the Flavivirus Infection of by Inducing Antimicrobial Peptides

- Fungal Chitin Dampens Inflammation through IL-10 Induction Mediated by NOD2 and TLR9 Activation

- Microbial Pathogens Trigger Host DNA Double-Strand Breaks Whose Abundance Is Reduced by Plant Defense Responses

- Alveolar Macrophages Are Essential for Protection from Respiratory Failure and Associated Morbidity following Influenza Virus Infection

- An Interaction between Glutathione and the Capsid Is Required for the Morphogenesis of C-Cluster Enteroviruses

- Concerted Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Imported DNA and ComE DNA Uptake Protein during Gonococcal Transformation

- Potent Dengue Virus Neutralization by a Therapeutic Antibody with Low Monovalent Affinity Requires Bivalent Engagement

- Regulation of Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type I Latency and Reactivation by HBZ and Rex

- Functionally Redundant RXLR Effectors from Act at Different Steps to Suppress Early flg22-Triggered Immunity

- The Pathogenic Mechanism of the Virulence Factor, Mycolactone, Depends on Blockade of Protein Translocation into the ER

- Role of Calmodulin-Calmodulin Kinase II, cAMP/Protein Kinase A and ERK 1/2 on -Induced Apoptosis of Head Kidney Macrophages

- An Overview of Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- First Experimental Model of Enhanced Dengue Disease Severity through Maternally Acquired Heterotypic Dengue Antibodies

- Binding of Glutathione to Enterovirus Capsids Is Essential for Virion Morphogenesis

- IFITM3 Restricts Influenza A Virus Entry by Blocking the Formation of Fusion Pores following Virus-Endosome Hemifusion

- Parasite Fate and Involvement of Infected Cells in the Induction of CD4 and CD8 T Cell Responses to

- Deficient IFN Signaling by Myeloid Cells Leads to MAVS-Dependent Virus-Induced Sepsis

- Pernicious Pathogens or Expedient Elements of Inheritance: The Significance of Yeast Prions

- The HMW1C-Like Glycosyltransferases—An Enzyme Family with a Sweet Tooth for Simple Sugars

- The Expanding Functions of Cellular Helicases: The Tombusvirus RNA Replication Enhancer Co-opts the Plant eIF4AIII-Like AtRH2 and the DDX5-Like AtRH5 DEAD-Box RNA Helicases to Promote Viral Asymmetric RNA Replication

- Mining Herbaria for Plant Pathogen Genomes: Back to the Future

- Inferring Influenza Infection Attack Rate from Seroprevalence Data

- A Human Lung Xenograft Mouse Model of Nipah Virus Infection

- Mast Cells Expedite Control of Pulmonary Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection by Enhancing the Recruitment of Protective CD8 T Cells to the Lungs

- Cytosolic Peroxidases Protect the Lysosome of Bloodstream African Trypanosomes from Iron-Mediated Membrane Damage

- Abortive T Follicular Helper Development Is Associated with a Defective Humoral Response in -Infected Macaques

- JC Polyomavirus Infection Is Strongly Controlled by Human Leucocyte Antigen Class II Variants

- Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides Promote Microbial Mutagenesis and Pathoadaptation in Chronic Infections

- Estimating the Fitness Advantage Conferred by Permissive Neuraminidase Mutations in Recent Oseltamivir-Resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 Influenza Viruses

- Progressive Accumulation of Activated ERK2 within Highly Stable ORF45-Containing Nuclear Complexes Promotes Lytic Gammaherpesvirus Infection

- Caspase-1-Like Regulation of the proPO-System and Role of ppA and Caspase-1-Like Cleaved Peptides from proPO in Innate Immunity

- Is Required for High Efficiency Viral Replication

- Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Triggers Type I IFN Production in Murine Conventional Dendritic Cells via a cGAS/STING-Mediated Cytosolic DNA-Sensing Pathway

- Evidence That Bank Vole PrP Is a Universal Acceptor for Prions

- Rapid Response to Selection, Competitive Release and Increased Transmission Potential of Artesunate-Selected Malaria Parasites

- Inactivation of Genes for Antigenic Variation in the Relapsing Fever Spirochete Reduces Infectivity in Mice and Transmission by Ticks

- Exposure-Dependent Control of Malaria-Induced Inflammation in Children

- A Neutralizing Anti-gH/gL Monoclonal Antibody Is Protective in the Guinea Pig Model of Congenital CMV Infection

- The Apical Complex Provides a Regulated Gateway for Secretion of Invasion Factors in

- A Highly Conserved Haplotype Directs Resistance to Toxoplasmosis and Its Associated Caspase-1 Dependent Killing of Parasite and Host Macrophage

- A Quantitative High-Resolution Genetic Profile Rapidly Identifies Sequence Determinants of Hepatitis C Viral Fitness and Drug Sensitivity

- Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Romidepsin Induces HIV Expression in CD4 T Cells from Patients on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy at Concentrations Achieved by Clinical Dosing

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The 2010 Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: How Science Solved a Controversy

- , , , Genetic Variability: Cryptic Biological Species or Clonal Near-Clades?

- Efficient Parvovirus Replication Requires CRL4-Targeted Depletion of p21 to Prevent Its Inhibitory Interaction with PCNA

- An Overview of Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání