-

Články

Reklama

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

ReklamaExpected and Unexpected Features of the Newly Discovered Bat Influenza A-like Viruses

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004819

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004819Summary

article has not abstract

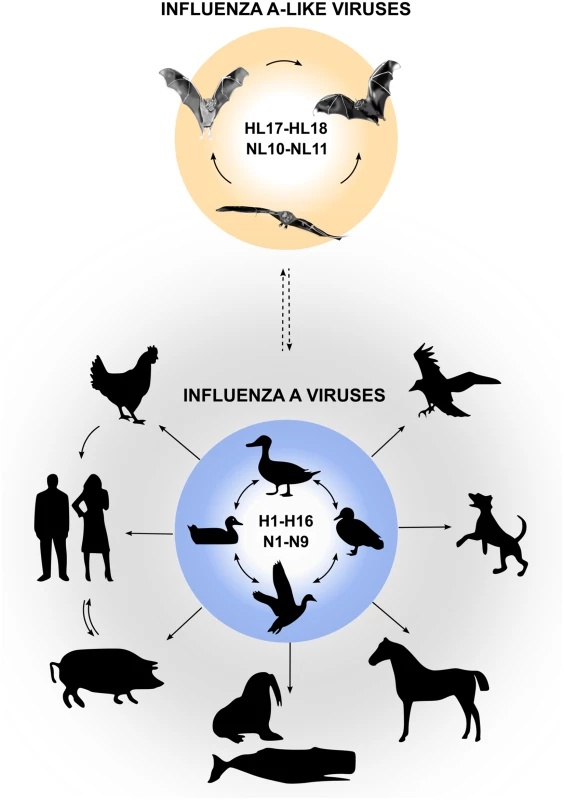

Influenza A viruses (IAVs) are important zoonotic pathogens that cause epidemic outbreaks in poultry, wild birds, swine, and other mammals. In humans, IAVs cause severe respiratory illness, and zoonotic transmission of IAVs from avian reservoirs poses a constant threat to the public health, as exemplified by the recent outbreak of an avian IAV of the H7N9 subtype [1]. Aquatic birds are considered to be the major reservoir of IAVs, and 16 hemagglutinin (HA) and nine neuraminidase (NA) viral subtypes have been isolated from avian species to date. It is now well documented that from time to time IAVs overcome the species barrier and establish new lineages in other animals, including domestic animals, sea mammals, and humans (Fig 1). Our understanding of IAVs was recently challenged by the identification of two novel genome sequences of influenza A-like viruses from bat specimens by next-generation sequencing. These viruses were provisionally designated “H17N10” (from yellow-shouldered fruit bats [Sturnira lilium] in Guatemala) and “H18N11” (from flat-faced fruit bats [Artibeus planirostris] in Peru) [2,3], which might signal an expansion of IAV host range (Fig 1).

Fig. 1. Reservoirs of IAVs and bat influenza-A-like viruses.

Natural reservoirs of classical IAVs are wild water birds, from which they can be transmitted to a wide variety of other species. Bat influenza A-like viruses are likely to circulate in various bat species in Central and South America and possibly originate from classical IAVs (indicated by dashed arrow). Are Bat Influenza A-like Viruses Different from Classical IAVs?

Biochemical and structural studies indicate that both the influenza A-like H17 and H18 proteins do not bind canonical sialic acid—containing receptors [3–5], which are bound by HAs of conventional IAVs for initiation of infection. Furthermore, the crystal structure of H17 and H18 revealed that these proteins possess a distorted putative sialic acid binding site and showed low thermostability when compared to all known well-characterized HAs [3,5]. In fact, H17 and H18 HAs are unable to bind and hemagglutinate red blood cells and therefore are not “true” HAs. Thus, we suggest that HAs from both H17 and H18 influenza A-like viruses should be named as “HA-like” (HL) proteins (HL17 and HL18).

Consistent with the observation that bat influenza A-like HL17 and HL18 do not bind to canonical sialic acid receptors, bat NAs lack detectable neuraminidase activity [6]. Although the overall N10 structure is similar to other known influenza NA structures, the region corresponding to the highly conserved active site in the N1–N9 subtypes is substantially different [6,7]. The structural features and the fact that the recombinant N10 protein exhibits no or extremely low NA activity suggests that it may have a different function than the NA proteins of other influenza viruses. We therefore suggest that N10 and N11 from bat influenza A-like viruses should be designated as “NA-like” (NL) proteins (NL10 and NL11). Furthermore, the current classification of bat influenza A-like viruses “H17N10 and H18N11” is misleading and should be reconsidered; we suggest that they can be designated as “HL17NL10 and HL18NL11”. At this moment, it is even unclear whether the receptor binding protein is the HL or the NL protein.

Bat Internal Proteins Are Similar to Those of Extant IAVs

Unlike the bat influenza A-like virus surface proteins, some of the internal proteins of HL17NL10 and HL18NL11 seem to be highly compatible with conventional IAVs [8,9]. This is mainly based on results from viral polymerase reconstitution experiments of a broad variety of IAVs, including the H1N1, H3N2, H5N1, and H7N9 subtypes [8–10]. In all cases, unimpaired polymerase activity was observed after substitution of the conventional IAV nucleoprotein (NP) with bat influenza A-like NP from either HL17NL10 or HL18NL11. Similarly, the polymerase subunit PB2 of both bat influenza A-like viruses partially supported the polymerase activity of some IAVs [8–10]. Internal proteins of HL17NL10 and HL18NL11 are fully compatible between each other, including the polymerase subunits [8]. Recently, the crystal structure of the bat influenza A-like virus polymerase complex was solved, providing a more detailed understanding of viral replication and transcription processes of bat influenza A-like viruses and IAVs in general [11]. This might be especially interesting for investigation of the polymerase compatibility between classical IAVs and bat influenza A-like viruses, as some of the polymerase subunits are interchangeable, whereas others are not.

Functional compatibility of the internal proteins of influenza A-like HL17NL10 with IAV was also observed in the formation of infectious virus-like particles (VLPs) of a conventional IAV [9]. Infectious VLPs of conventional IAVs could be reconstituted with NP, matrix protein 1 (M1), or combinations of HL17NL10 proteins such as the polymerase complex, or M1 and M2, or all internal proteins. Therefore, the internal proteins of bat influenza A-like viruses seem to be functionally equivalent to conventional IAV proteins. This functional compatibility seems to be restricted to IAVs, since bat influenza A-like NPs, as well as the polymerase subunits, do not support the polymerase activity of influenza B viruses [8].

Are Bats a Reservoir for Bat Influenza A-like Viruses and Classical Influenza A Viruses?

Serological surveys indicate that influenza A-like viruses of the HL17 or HL18 subtypes circulate in various bat species in Central and South America, including predominantly Sturnira sp., A. planirostris, Artibeus lituratus, Carollia perspicillata, Myotis sp., Molossus molossus, and others (Fig 1) [3]. These studies also demonstrated that up to 50% of tested samples collected from different bat species in South America are seropositive to HL18 or NL11, and specific antibodies to HL17 are found in 38% of samples collected from nine bat species in Central America [3], suggesting that widespread circulation of bat influenza A-like viruses exists among bats in Central and South America. However, formal proof of transmission events between bat species is missing. Whether bats are infected with other influenza A-like virus subtypes is currently unknown. Moreover, it also remains unclear whether bat influenza A-like HL17NL10 and HL18NL11 viruses can be found outside of Central and South America. Based on a reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) screen that allows detection of HL17NL10 only, central European bats seem to be free of this influenza A-like virus subtype [12]. Although classical IAVs can be isolated from bats in rare cases and antibodies against IAVs were also detected in bats [13], there is no evidence for the infection of New World bats with classical IAVs of the H1 and H5 subtype [3].

How Can We Study These Bat Influenza A-like Viruses?

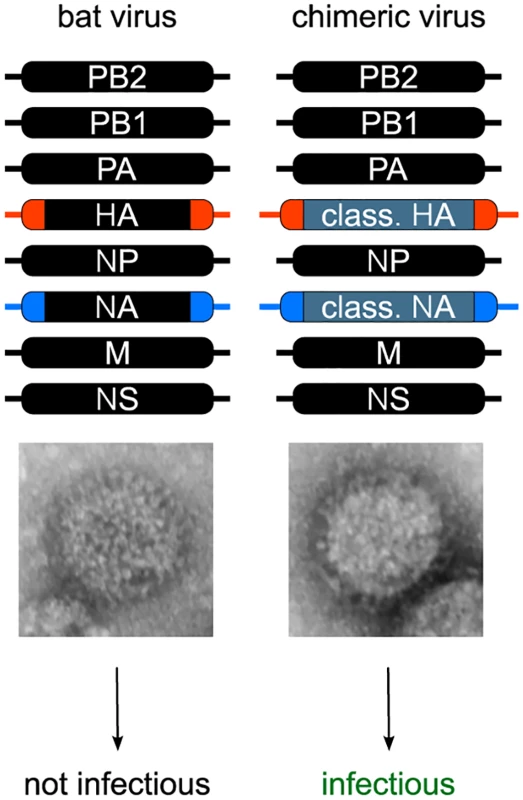

All efforts to isolate an infectious virus from bat species have failed to date, although HL17NL10 or HL18NL11 RT-PCR-positive tissue and rectal swab samples were used in these studies [2,3]. The challenge in isolating infectious influenza A-like viruses could also be related to the atypical surface proteins of these viruses, especially since there is no evidence that the cell lines used for virus isolation, including bat, human, canine, and avian cells [2,3,8,9], express the receptors that allow viral particle uptake. It might be then not surprising that the generation of wild-type influenza A-like HL17NL10 or HL18NL11 viruses using reverse genetic approaches has not succeeded. However, from these rescue attempts, we learned by electron microscopy studies that viral particles are released from human HEK293T cells (Fig 2) [8]. Thus, subsequent binding and internalization of the viral particles in different cells that are normally used for the amplification of recombinant IAV might be impaired.

Fig. 2. Generation of recombinant bat chimeric influenza viruses.

Although rescue attempts with a complete authentic set of either HL17NL10 or HL18NL11 genome segments resulted in the release of viral particles as evidenced by electron microscopy (HL17NL10 particle is shown), no viral growth was observed in various cell culture systems. In contrast, recombinant bat chimeric viruses encoding HA and NA of classical IAVs were highly infectious. Successful rescue of bat chimeric viruses requires bat virus specific packaging sequences (highlighted in blue and red), including the noncoding region and part of the bat virus gene segment 3′ and 5′ open reading frame. Recently, we succeeded in generating chimeric bat viruses in mammalian cells containing six internal genes from either influenza A-like HL17NL10 or HL18NL11 virus, with the remaining two surface genes encoding the HA and NA from a conventional IAV such as A/PR/8/1934 (H1N1), A/swine/Texas/4199-2/1998 (H3N2), or A/SC35M (H7N7) [8,9]. To rescue these bat chimeras, it was essential to flank the canonical IAV HA and NA coding regions with the noncoding regions and part of the coding regions from the bat influenza A-like HA (HL17 or HL18) and NA (NL10 or NL11) segments, indicating RNA packaging incompatibilities between bat influenza A-like virus and conventional IAV segments (Fig 2). The major packaging sequences of conventional IAV are located within these regions [14,15] and vary only slightly, thereby allowing reassortment of viral genomes between different IAVs [16]. For efficient growth of bat chimeric viruses in mammalian cells or mice, adaptive mutations are not necessarily required. However, viral replication and pathogenicity in mice is dependent to a certain degree on the HA/NA combination used [8]. The HL17NL10-based bat chimeric virus with the viral surface glycoproteins of a mouse adapted H7N7 virus (A/SC35M) shows limited replication and no pathogenicity in mice [9], while mice infected with a comparable virus dose of the chimera with HA and NA coding regions from A/PR8/H1N1 died from extensive lung pathology, typically observed with conventional IAV [8]. Whether this is due to an intrinsic feature of the different HA/NAs or the interplay between viral surface glycoproteins and internal genes of the bat influenza A-like viruses remains to be determined.

What Is the Zoonotic Potential of These Bat Influenza A-like Viruses?

Several lines of evidence indicate that bat influenza A-like viruses are of low risk for the human population. This is based on the observation that viral particles of HL17NL10 or HL18NL11 generated by reverse genetics failed to productively infect human cells, which correlates with the general inability of the bat HAs and NAs to mediate cell entry into these cells [3,4,7]. An important feature of an IAV is the possibility to exchange genomic RNA segments with other IAVs, resulting in novel genotypes and phenotypes with zoonotic potential. However, coinfection experiments demonstrated no reassortment between bat chimeric viruses and conventional IAVs [8,9]. The larger sequence diversity between bat influenza A-like virus and conventional IAV genomes most likely caused this packaging incompatibility between these viruses. In addition, specific incompatibilities at the protein level might further prevent the emergence of reassortant viruses after coinfection occurrence. This especially includes the bat influenza A-like polymerase subunits PB1 and PA, since these two proteins do not support the polymerase activity of conventional IAVs [8,9].

Future Directions

Despite considerable progress, there are many questions that remain to be addressed: How can we propagate infectious viruses in vitro for further studies? What is the receptor and is it specific for bats? Are there more influenza and influenza-like viruses circulating in bats or other hosts in Central and South America and other parts of the world? If so, do these viruses pose a risk for domestic animals and/or humans as observed in bat-derived severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), rabies, Nipah, and probably Ebola viruses?

Zdroje

1. Zhou J, Wang D, Gao R, Zhao B, Song J, et al. (2013) Biological features of novel avian influenza A (H7N9) virus. Nature 499 : 500–503. doi: 10.1038/nature12379 23823727

2. Tong S, Li Y, Rivailler P, Conrardy C, Castillo DA, et al. (2012) A distinct lineage of influenza A virus from bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 4269–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116200109 22371588

3. Tong S, Zhu X, Li Y, Shi M, Zhang J, et al. (2013) New world bats harbor diverse influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003657. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003657 24130481

4. Sun X, Shi Y, Lu X, He J, Gao F, et al. (2013) Bat-derived influenza hemagglutinin H17 does not bind canonical avian or human receptors and most likely uses a unique entry mechanism. Cell Rep 3 : 769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.025 23434510

5. Wu Y, Tefsen B, Shi Y, Gao GF (2014) Bat-derived influenza-like viruses H17N10 and H18N11. Trends Microbiol 22 : 183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.01.010 24582528

6. Li Q, Sun X, Li Z, Liu Y, Vavricka CJ, et al. (2012) Structural and functional characterization of neuraminidase-like molecule N10 derived from bat influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 18897–18902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211037109 23012237

7. Zhu X, Yang H, Guo Z, Yu W, Carney PJ, et al. (2012) Crystal structures of two subtype N10 neuraminidase-like proteins from bat influenza A viruses reveal a diverged putative active site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 18903–18908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212579109 23012478

8. Zhou B, Ma J, Liu Q, Bawa B, Wang W, et al. (2014) Characterization of uncultivable bat influenza virus using a replicative synthetic virus. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004420. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004420 25275541

9. Juozapaitis M, Aguiar Moreira E, Mena I, Giese S, Riegger D, et al. (2014) An infectious bat-derived chimeric influenza virus harbouring the entry machinery of an influenza A virus. Nat Commun 5 : 4448. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5448 25055345

10. Poole DS, Yu S, Cai Y, Dinis JM, Muller MA, et al. (2014) Influenza A virus polymerase is a site for adaptive changes during experimental evolution in bat cells. J Virol 88 : 12572–12585. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01857-14 25142579

11. Pflug A, Guilligay D, Reich S, Cusack S (2014) Structure of influenza A polymerase bound to the viral RNA promoter. Nature 516 : 355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature14008 25409142

12. Fereidouni S, Kwasnitschka L, Balkema Buschmann A, Muller T, Freuling C, et al. (2014) No Virological Evidence for an Influenza A—like Virus in European Bats. Zoonoses Public Health 62 : 187–189. doi: 10.1111/zph.12131 24837569

13. Mehle A (2014) Unusual influenza A viruses in bats. Viruses 6 : 3438–3449. doi: 10.3390/v6093438 25256392

14. Watanabe T, Watanabe S, Noda T, Fujii Y, Kawaoka Y (2003) Exploitation of nucleic acid packaging signals to generate a novel influenza virus-based vector stably expressing two foreign genes. J Virol 77 : 10575–10583. 12970442

15. Hutchinson EC, von Kirchbach JC, Gog JR, Digard P (2009) Genome packaging in influenza A virus. J Gen Virol 91 : 313–328. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.017608-0 19955561

16. Gao Q, Palese P (2009) Rewiring the RNAs of influenza virus to prevent reassortment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 15891–15896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908897106 19805230

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Clearance of Pneumococcal Colonization in Infants Is Delayed through Altered Macrophage TraffickingČlánek An Model of Latency and Reactivation of Varicella Zoster Virus in Human Stem Cell-Derived NeuronsČlánek Protective mAbs and Cross-Reactive mAbs Raised by Immunization with Engineered Marburg Virus GPsČlánek Specific Cell Targeting Therapy Bypasses Drug Resistance Mechanisms in African TrypanosomiasisČlánek Peptidoglycan Branched Stem Peptides Contribute to Virulence by Inhibiting Pneumolysin ReleaseČlánek HIV Latency Is Established Directly and Early in Both Resting and Activated Primary CD4 T CellsČlánek Sequence-Specific Fidelity Alterations Associated with West Nile Virus Attenuation in Mosquitoes

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 6- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Introducing “Research Matters”

- Exploring Host–Pathogen Interactions through Biological Control

- Analysis of Bottlenecks in Experimental Models of Infection

- Expected and Unexpected Features of the Newly Discovered Bat Influenza A-like Viruses

- Clearance of Pneumococcal Colonization in Infants Is Delayed through Altered Macrophage Trafficking

- Recombinant Murine Gamma Herpesvirus 68 Carrying KSHV G Protein-Coupled Receptor Induces Angiogenic Lesions in Mice

- TRIM30α Is a Negative-Feedback Regulator of the Intracellular DNA and DNA Virus-Triggered Response by Targeting STING

- Targeting Human Transmission Biology for Malaria Elimination

- Two Cdc2 Kinase Genes with Distinct Functions in Vegetative and Infectious Hyphae in

- An Model of Latency and Reactivation of Varicella Zoster Virus in Human Stem Cell-Derived Neurons

- Protective mAbs and Cross-Reactive mAbs Raised by Immunization with Engineered Marburg Virus GPs

- Virulence Factors of Induce Both the Unfolded Protein and Integrated Stress Responses in Airway Epithelial Cells

- Peptide-MHC-I from Endogenous Antigen Outnumber Those from Exogenous Antigen, Irrespective of APC Phenotype or Activation

- Specific Cell Targeting Therapy Bypasses Drug Resistance Mechanisms in African Trypanosomiasis

- An Ultrasensitive Mechanism Regulates Influenza Virus-Induced Inflammation

- The Role of Human Transportation Networks in Mediating the Genetic Structure of Seasonal Influenza in the United States

- Host Delivery of Favorite Meals for Intracellular Pathogens

- Complement-Opsonized HIV-1 Overcomes Restriction in Dendritic Cells

- Inter-Seasonal Influenza is Characterized by Extended Virus Transmission and Persistence

- A Critical Role for CLSP2 in the Modulation of Antifungal Immune Response in Mosquitoes

- Twilight, a Novel Circadian-Regulated Gene, Integrates Phototropism with Nutrient and Redox Homeostasis during Fungal Development

- Surface-Associated Lipoproteins Link Virulence to Colitogenic Activity in IL-10-Deficient Mice Independent of Their Expression Levels

- Latent Membrane Protein LMP2A Impairs Recognition of EBV-Infected Cells by CD8+ T Cells

- Bank Vole Prion Protein As an Apparently Universal Substrate for RT-QuIC-Based Detection and Discrimination of Prion Strains

- Neuronal Subtype and Satellite Cell Tropism Are Determinants of Varicella-Zoster Virus Virulence in Human Dorsal Root Ganglia Xenografts

- Molecular Basis for the Selective Inhibition of Respiratory Syncytial Virus RNA Polymerase by 2'-Fluoro-4'-Chloromethyl-Cytidine Triphosphate

- Structure of the Virulence Factor, SidC Reveals a Unique PI(4)P-Specific Binding Domain Essential for Its Targeting to the Bacterial Phagosome

- Activated Brain Endothelial Cells Cross-Present Malaria Antigen

- Fungal Morphology, Iron Homeostasis, and Lipid Metabolism Regulated by a GATA Transcription Factor in

- Peptidoglycan Branched Stem Peptides Contribute to Virulence by Inhibiting Pneumolysin Release

- A Macrophage Subversion Factor Is Shared by Intracellular and Extracellular Pathogens

- A Novel AT-Rich DNA Recognition Mechanism for Bacterial Xenogeneic Silencer MvaT

- Reovirus FAST Proteins Drive Pore Formation and Syncytiogenesis Using a Novel Helix-Loop-Helix Fusion-Inducing Lipid Packing Sensor

- The Role of ExoS in Dissemination of during Pneumonia

- IRF-5-Mediated Inflammation Limits CD8 T Cell Expansion by Inducing HIF-1α and Impairing Dendritic Cell Functions during Infection

- Discordant Impact of HLA on Viral Replicative Capacity and Disease Progression in Pediatric and Adult HIV Infection

- Crystal Structure of USP7 Ubiquitin-like Domains with an ICP0 Peptide Reveals a Novel Mechanism Used by Viral and Cellular Proteins to Target USP7

- HIV Latency Is Established Directly and Early in Both Resting and Activated Primary CD4 T Cells

- HPV16 Down-Regulates the Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein 2 to Promote Epithelial Invasion in Organotypic Cultures

- The νSaα Specific Lipoprotein Like Cluster () of . USA300 Contributes to Immune Stimulation and Invasion in Human Cells

- RSV-Induced H3K4 Demethylase KDM5B Leads to Regulation of Dendritic Cell-Derived Innate Cytokines and Exacerbates Pathogenesis

- Leukocidin A/B (LukAB) Kills Human Monocytes via Host NLRP3 and ASC when Extracellular, but Not Intracellular

- Border Patrol Gone Awry: Lung NKT Cell Activation by Exacerbates Tularemia-Like Disease

- The Curious Road from Basic Pathogen Research to Clinical Translation

- From Cell and Organismal Biology to Drugs

- Adenovirus Tales: From the Cell Surface to the Nuclear Pore Complex

- A 21st Century Perspective of Poliovirus Replication

- Is Development of a Vaccine against Feasible?

- Waterborne Viruses: A Barrier to Safe Drinking Water

- Battling Phages: How Bacteria Defend against Viral Attack

- Archaea in and on the Human Body: Health Implications and Future Directions

- Degradation of Human PDZ-Proteins by Human Alphapapillomaviruses Represents an Evolutionary Adaptation to a Novel Cellular Niche

- Natural Variants of the KPC-2 Carbapenemase have Evolved Increased Catalytic Efficiency for Ceftazidime Hydrolysis at the Cost of Enzyme Stability

- Potent Cell-Intrinsic Immune Responses in Dendritic Cells Facilitate HIV-1-Specific T Cell Immunity in HIV-1 Elite Controllers

- The Mammalian Cell Cycle Regulates Parvovirus Nuclear Capsid Assembly

- Host Reticulocytes Provide Metabolic Reservoirs That Can Be Exploited by Malaria Parasites

- The Proteome of the Isolated Containing Vacuole Reveals a Complex Trafficking Platform Enriched for Retromer Components

- NK-, NKT- and CD8-Derived IFNγ Drives Myeloid Cell Activation and Erythrophagocytosis, Resulting in Trypanosomosis-Associated Acute Anemia

- Successes and Challenges on the Road to Cure Hepatitis C

- BRCA1 Regulates IFI16 Mediated Nuclear Innate Sensing of Herpes Viral DNA and Subsequent Induction of the Innate Inflammasome and Interferon-β Responses

- A Structural and Functional Comparison Between Infectious and Non-Infectious Autocatalytic Recombinant PrP Conformers

- Phosphorylation of the Peptidoglycan Synthase PonA1 Governs the Rate of Polar Elongation in Mycobacteria

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Nef Inhibits Autophagy through Transcription Factor EB Sequestration

- Sequence-Specific Fidelity Alterations Associated with West Nile Virus Attenuation in Mosquitoes

- EBV BART MicroRNAs Target Multiple Pro-apoptotic Cellular Genes to Promote Epithelial Cell Survival

- Single-Cell and Single-Cycle Analysis of HIV-1 Replication

- TRIM32 Senses and Restricts Influenza A Virus by Ubiquitination of PB1 Polymerase

- The Herpes Simplex Virus Protein pUL31 Escorts Nucleocapsids to Sites of Nuclear Egress, a Process Coordinated by Its N-Terminal Domain

- Host Transcriptional Response to Influenza and Other Acute Respiratory Viral Infections – A Prospective Cohort Study

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- HIV Latency Is Established Directly and Early in Both Resting and Activated Primary CD4 T Cells

- Battling Phages: How Bacteria Defend against Viral Attack

- A 21st Century Perspective of Poliovirus Replication

- Adenovirus Tales: From the Cell Surface to the Nuclear Pore Complex

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání