-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaInvestigation of Acetylcholine Receptor Diversity in a Nematode Parasite Leads to Characterization of Tribendimidine- and Derquantel-Sensitive nAChRs

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) of parasitic nematodes are required for body movement and are targets of important “classical” anthelmintics like levamisole and pyrantel, as well as “novel” anthelmintics like tribendimidine and derquantel. Four biophysical subtypes of nAChR have been observed electrophysiologically in body muscle of the nematode parasite Oesophagostomum dentatum, but their molecular basis was not understood. Additionally, loss of one of these subtypes (G 35 pS) was found to be associated with levamisole resistance. In the present study, we identified and expressed in Xenopus oocytes, four O. dentatum nAChR subunit genes, Ode-unc-38, Ode-unc-63, Ode-unc-29 and Ode-acr-8, to explore the origin of the receptor diversity. When different combinations of subunits were injected in Xenopus oocytes, we reconstituted and characterized four pharmacologically different types of nAChRs with different sensitivities to the cholinergic anthelmintics. Moreover, we demonstrate that the receptor diversity may be affected by the stoichiometric arrangement of the subunits. We show, for the first time, different combinations of subunits from a parasitic nematode that make up receptors sensitive to tribendimidine and derquantel. In addition, we report that the recombinant levamisole-sensitive receptor made up of Ode-UNC-29, Ode-UNC-63, Ode-UNC-38 and Ode-ACR-8 subunits has the same single-channel conductance, 35 pS and 2.4 ms mean open-time properties, as the levamisole-AChR (G35) subtype previously identified in vivo. These data highlight the flexible arrangements of the receptor subunits and their effects on sensitivity and resistance to the cholinergic anthelmintics; pyrantel, tribendimidine and/or derquantel may still be effective on levamisole-resistant worms.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003870

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003870Summary

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) of parasitic nematodes are required for body movement and are targets of important “classical” anthelmintics like levamisole and pyrantel, as well as “novel” anthelmintics like tribendimidine and derquantel. Four biophysical subtypes of nAChR have been observed electrophysiologically in body muscle of the nematode parasite Oesophagostomum dentatum, but their molecular basis was not understood. Additionally, loss of one of these subtypes (G 35 pS) was found to be associated with levamisole resistance. In the present study, we identified and expressed in Xenopus oocytes, four O. dentatum nAChR subunit genes, Ode-unc-38, Ode-unc-63, Ode-unc-29 and Ode-acr-8, to explore the origin of the receptor diversity. When different combinations of subunits were injected in Xenopus oocytes, we reconstituted and characterized four pharmacologically different types of nAChRs with different sensitivities to the cholinergic anthelmintics. Moreover, we demonstrate that the receptor diversity may be affected by the stoichiometric arrangement of the subunits. We show, for the first time, different combinations of subunits from a parasitic nematode that make up receptors sensitive to tribendimidine and derquantel. In addition, we report that the recombinant levamisole-sensitive receptor made up of Ode-UNC-29, Ode-UNC-63, Ode-UNC-38 and Ode-ACR-8 subunits has the same single-channel conductance, 35 pS and 2.4 ms mean open-time properties, as the levamisole-AChR (G35) subtype previously identified in vivo. These data highlight the flexible arrangements of the receptor subunits and their effects on sensitivity and resistance to the cholinergic anthelmintics; pyrantel, tribendimidine and/or derquantel may still be effective on levamisole-resistant worms.

Introduction

Human nematode parasite infections are of public health concern in many developing countries where over a billion people are infected [1], [2]. Also very important for human nutrition are infections of livestock which cause significant production loss [3]. Treatment and prophylaxis for these nematode infections requires the use of anthelmintic drugs because sanitation is limited and vaccines are not available. Disturbingly, the regular use of anthelmintics has now been associated with treatment failures and gives rise to concerns about the development of resistance. Resistance has been seen, for example, against levamisole and pyrantel in animals [4]. These two ‘classic’ anthelmintics work by selectively opening ligand-gated nicotinic acetylcholine (nAChR) ion-channels of nematode muscle to produce depolarization, entry of calcium, contraction and spastic paralysis [5]. The nAChR is composed of 5 transmembrane subunits which surround the cation permeable channel pore. The importance of nAChRs has increased recently because of the introduction of novel cholinergic anthelmintics including: the agonist tribendimidine, which has been approved for human use in China [6]; the allosteric modulator monepantel [7], [8]; and the antagonist derquantel [9]. Tribendimidine is a symmetrical diamidine derivative of amidantel effective against Ascaris, hookworms, Strongyloides stercolaris, trematodes and tapeworms [10]. Molecular experiments using the free-living model nematode C. elegans suggest that tribendimidine acts as a cholinergic agonist like levamisole and pyrantel [11]. Derquantel is a 2-desoxo derivative of paraherquamide in the spiroindole drug class effective against various species of parasitic nematodes, particularly the trichostrongylid nematodes [12]. Derquantel is a selective competitive antagonist of nematode muscle nAChRs especially on the B-subtype nAChR from Ascaris suum [13]. In contrast to levamisole and pyrantel sensitive-nAChRs [14], [15], [16], the molecular basis for the action of tribendimidine and derquantel in parasitic nematodes are still not known. The chemical structures of the cholinergic anthelmintics are different and resistance to one of the cholinergic anthelmintics sometimes does not give rise to cross-resistance to other cholinergic anthelmintics [17]. These observations imply that the nAChR subtypes in nematode parasites may represent distinct pharmacological targets sensitive to different cholinergic anthelmintics. Therefore, in the present work, we have investigated mechanistic explanations for the variability and diversity of the cholinergic receptors of parasitic nematodes and their therapeutic significance.

The model nematode, C. elegans, possesses two muscle nAChR types: one sensitive to levamisole and one sensitive to nicotine [18]. The levamisole AChR type is composed of the five subunits, Cel-UNC-29, Cel-UNC-38, Cel-UNC-63, Cel-LEV-1 and Cel-LEV-8 [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. The nicotine-AChR type is a homopentamer composed of Cel-ACR-16 subunits [23]. In Ascaris suum, there are three pharmacologically separate nAChR types on the body muscle: the N-type that is preferentially activated by nicotine; the L-type that is preferentially activated by levamisole and; the B-type that is preferentially activated by bephenium [13]. In Oesophagostomum dentatum there are four muscle nAChRs which are defined by their single-channel conductances: G 25 pS, G 35 pS, G 40 pS and G 45 pS. The G 35 pS receptor type of O. dentatum is reduced in a levamisole-resistant isolate [24] but not in a pyrantel-resistant isolate [25]. Interestingly, the G 35 pS type of O. dentatum has a similar channel conductance to the L-type from the distantly related species, A. suum [13].

However, the precise molecular mechanisms of levamisole and pyrantel resistance occurring in O. dentatum isolates are still unknown because the O. dentatum genes encoding muscle nAChR subunits have not yet been identified. In order to determine a mechanistic explanation for the variability and pharmacological diversity of the muscle nAChR types in parasitic nematodes like Oesophagostomum dentatum, we took advantage of the Xenopus oocyte expression system [14], [26], [27].

In this study our first objective was to clone the four putative subunit genes Ode-unc-38, Ode-unc-29 Ode-unc-63 and Ode-acr-8, which are homologues of the C. elegans levamisole muscle receptor genes [15], [16] and express them in Xenopus laevis oocytes to recapitulate the levamisole-sensitive AChRs of O. dentatum. In a previous study on H. contortus which is closely related to O. dentatum, we have reported that co-expression of four AChR subunits (Hco-UNC-38, Hco-UNC-63, Hco-UNC-29 and Hco-ACR-8) in Xenopus oocytes resulted in the robust expression of a levamisole sensitive nAChR [16]. In the present work we have identified and cloned the homologs of the corresponding genes in O. dentatum (Ode-unc-38, Ode-unc-63, Ode-unc-29 and Ode-acr8) and express them in Xenopus oocytes. Of particular note is the evidence that these receptor subtypes are pharmacological targets of the new anthelmintic tribendimidine. Moreover, we demonstrate that the nAChR reconstituted with all four subunits is more sensitive to levamisole than pyrantel and has a single channel conductance of 35 pS, corresponding to the L-type previously observed in vivo in O. dentatum and A. suum. Another receptor type, made of 3 subunits, was more sensitive to pyrantel and the new anthelmintic derquantel had a selective effect against receptors activated by pyrantel rather than levamisole, providing the first insight of its molecular target composition in any parasitic nematode. These results provide a basis for understanding the greater diversity of the nAChR repertoire from parasitic nematodes and for deciphering the physiological role of nAChR subtypes targeted by distinct cholinergic anthelmintics. This study will facilitate more rational use of cholinergic agonists/antagonists for the sustainable control of parasitic nematodes impacting both human and animal health.

Results

Identification of unc-29, acr-8, unc-38 and unc-63 homologues from O. dentatum and phylogenetic comparison to related nematode species

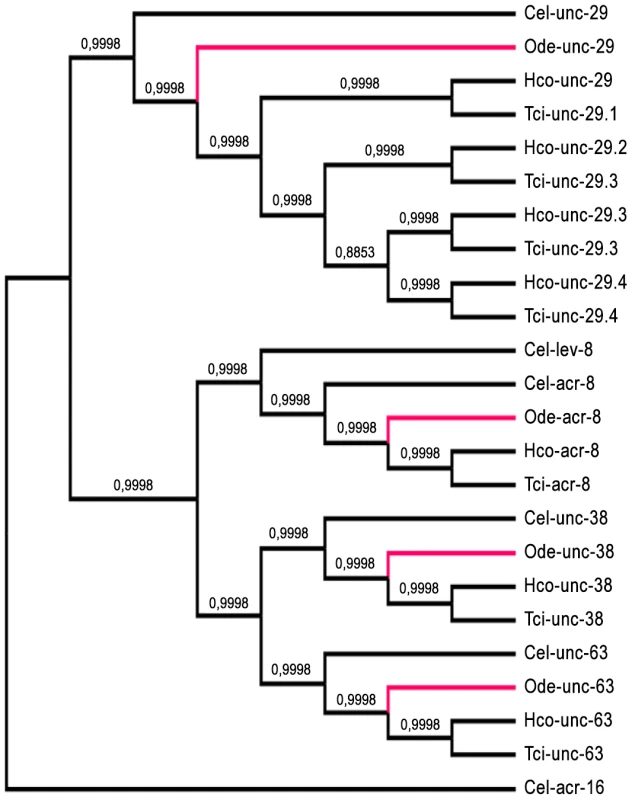

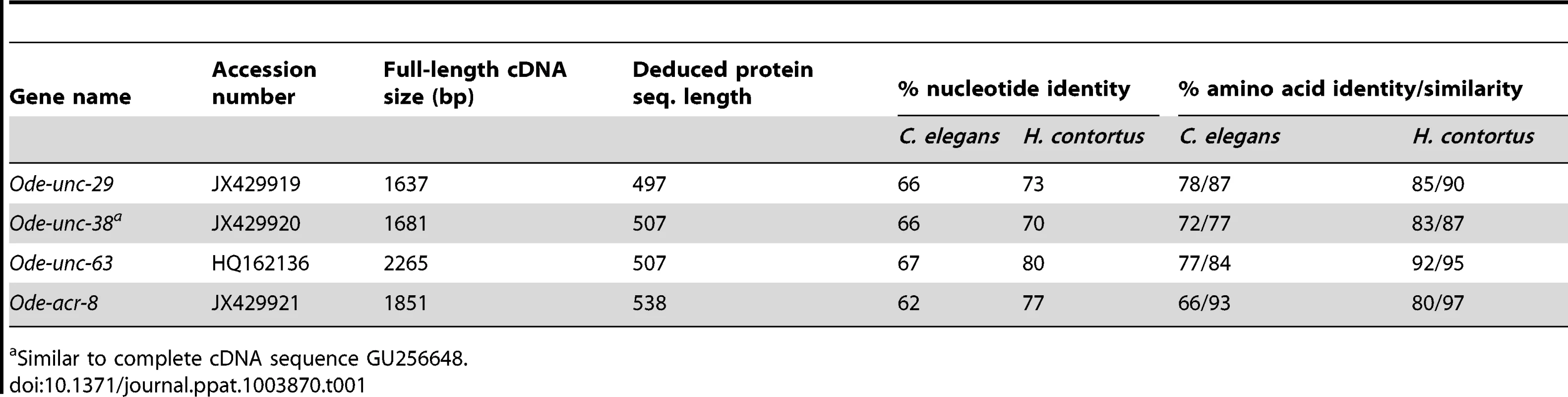

Taking advantage of the phylogenetic closeness of O. dentatum, C. elegans and H. contortus in clade V of the nematode phylum, we used a candidate gene approach to identify full-length subunit cDNAs from O. dentatum of unc-63, unc-29 and acr-8 homologues. The previously available O. dentatum unc-38-like full-length cDNA sequence (Accession number GU256648) allowed the rapid cloning of the Ode-unc-38 subunit cDNA. The UNC-38 and UNC-63 subunits being closely related in the UNC-38 “core” group [28], multi-alignment of unc-63 and unc-38 cDNA sequences from different nematode species allowed the design of degenerate primers that were able to specifically amplify the unc-63 homologue from O. dentatum. To identify the unc-29 homologue from O. dentatum, degenerate primers from the H. contortus and C. elegans unc-29 sequences were used to amplify a partial 288 bp cDNA sequence, providing specific information to get the full-length cDNA by RACE-PCR standard procedures. To identify the acr-8 homologue from O. dentatum, a partial cDNA of 861 bp was cloned using primers from H. contortus acr-8, allowing subsequent identification of the full-length cDNA encoding Ode-ACR-8 subunit. The four O. dentatum subunit transcripts were trans-spliced at their 5′end with the splice leader 1 (SL1). The predicted nAChR proteins displayed typical features of LGIC subunits including a secretion signal peptide, a cys-loop domain consisting of 2 cysteines separated by 13 amino acid residues and four transmembrane domains (TM1-4) (supplemental figure S1A–D). The Ode-UNC-38, Ode-UNC-63 and Ode-ACR-8 subunits contained in their N-terminal part the Yx(x)CC motif characteristic of the α-type subunits whereas the Ode-UNC-29 subunit sequence lacked these vicinal di-cysteines. The different nAChR subunit sequences, accession numbers, characteristics and closest levamisole subunit homologues of C. elegans and H. contortus are presented in Table 1. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of the four O. dentatum nAChR subunits revealed 66 to 92% identity with their respective homologues from C. elegans and H. contortus (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S1A–D), indicating that even in closely related species some interspecies polymorphisms could impact the nAChR subunit composition and pharmacological properties. The phylogenies shown in Fig. 1 (maximum likelihood tree) and supplemental Fig. S2 (distance tree) identify a single ortholog each for the unc-38, unc-63, acr-8, and unc-29 subunits in O. dentatum. The branching topology is consistent, in each case, with a taxonomic position of O. dentatum with strongylida and outside the trichstrongyloidea [29]. Interestingly, this topology places the speciation of O. dentatum significantly before the previously identified trichostrongylid specific unc-29 diversification event [15]. As such, these duplications cannot be shared with O. dentatum, although it is not possible to rule out other independent unc-29 duplication events in O. dentatum. Clearly, further studies that include analysis of unc-29 homolog sequences in a wide range of nematode species are required to understand the evolutionary impact of such duplication events.

Fig. 1. Maximum likelihood tree showing relationships of acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunit cDNA sequences in Oesophagostomum dentatum (Ode, highlighted in red), Caenorhabditis elegans (Cel), Haemonchus contortus (Hco) and Teladorsagia circumcincta (Tci).

The C. elegans acr-16 nAChR subunit sequence was used as an outgroup. Branch support was evaluated using the chi2 option of PhyML and values more than 0.9 were considered reliable. Tab. 1. Comparison of O. dentatum AChR subunits with the homologs of C. elegans and H. contortus.

Similar to complete cDNA sequence GU256648. Expression of Ode(29–63), the Pyr-nAChR and stoichiometry effect on pharmacological properties

Our investigation of O. dentatum receptor expression determined the minimum number of subunits that is required to reconstitute a functional muscle nAChR. Previous expression studies of C. elegans and H. contortus functional nAChRs in Xenopus oocytes required the use of ancillary proteins [16], [26]. Hence, the H. contortus ancillary factors Hco-ric-3, Hco-unc-50 and Hco-unc-74 were also injected to facilitate the expression of O. dentatum functional receptors in Xenopus oocytes. In control experiments we observed that oocytes injected with ancillary protein cRNAs did not produce current responses to 100 µM acetylcholine or other cholinergic anthelmintics. We then injected different combinations of pairs of cRNAs (1∶1) of: Ode-unc-29, Ode-unc-38, Ode-unc-63 and Ode-acr-8.

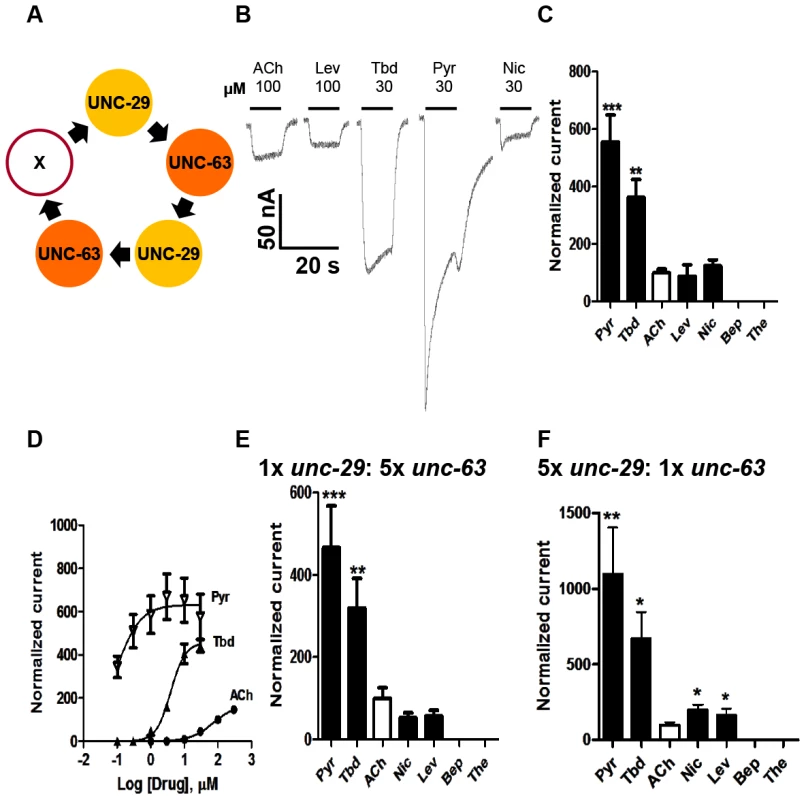

Only those oocytes injected with 1∶1 Ode-unc29∶Ode-unc-63 cRNA, regularly produced currents of >50 nA in response to 100 µM acetylcholine or cholinergic anthelmintics, indicating that the two subunits could form functional receptors (Fig. 2). We found that no other paired combination produced currents. Without both subunits in any of our subsequent injected mixes, no functional receptor could be reconstituted, demonstrating that Ode-UNC-29 and Ode-UNC-63 are essential O. dentatum levamisole receptor subunits. Injection of each of these subunits alone did not form receptors that responded to the agonists we tested, demonstrating that these subunits do not form homopentamers.

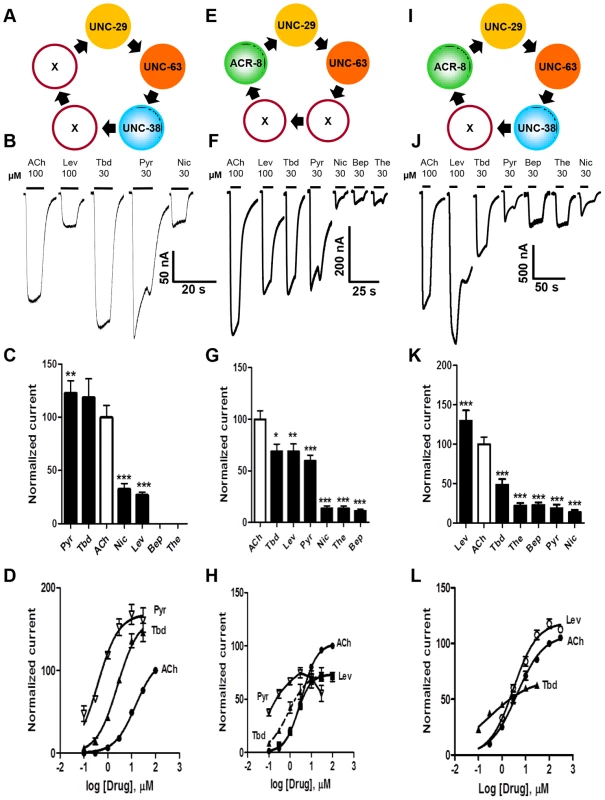

Fig. 2. Voltage-clamp of oocytes injected with O. dentatum Ode-unc-29 and Ode-unc-63 nAChR subunits.

(A) Diagram of possible subunit arrangements of Ode-unc-29 and Ode-unc-63. X represents either UNC-63 or UNC-29 subunit. PyR, pyrantel; Tbd, tribendimidine, ACh, acetylcholine; Nic, nicotine; Bep, bephenium; The, thenium. (B) Representative traces showing the inward currents in oocytes injected with 1∶1 Ode-unc-29 and Ode-unc-63. (C) Bar chart (mean ± se) of agonists-elicited currents in the Ode-(29 - 63) Pyr-nAChR, (paired t-test, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). All agonist responses have been normalized to the average 100 µM ACh currents. (D) Dose-response relationships for Pyr (inverted Δ, n = 6), Tbd (▴, n = 5) and ACh (•, n = 6) in the Ode-(29 - 63) Pyr-nAChR, (n = number of oocytes). (E) Bar chart (mean ± se) of normalized currents elicited by different agonists in 1∶5 Ode-unc-29∶Ode-unc-63 injected oocytes. Currents have been normalized to and compared with 100 µM ACh currents (paired t-test, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (F) Bar chart (mean ± se) of normalized currents elicited by different agonists in oocytes injected with 5∶1 Ode-unc-29∶Ode-unc-63. Currents normalized to and compared with 100 µM ACh currents (paired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). More than 75% of injected oocytes responded to acetylcholine. For our standard test concentrations, except for 100 µM acetylcholine and 100 µM levamisole, we used 30 µM drug concentrations of different important anthelmintics to limit effects of open-channel block. Interestingly, the novel anthelmintic tribendimidine elicited currents when perfused on oocytes expressing Ode-UNC-29 and Ode-UNC-63. The potency series of the agonists (anthelmintics) based on the normalized currents, Fig. 2C, was: 30 µM pyrantel >30 µM tribendimidine >30 µM nicotine ≈100 µM levamisole ≈100 µM acetylcholine. Neither 30 µM bephenium, nor 30 µM thenium, were active. Even at 30 µM, pyrantel produced currents bigger than 100 µM acetylcholine (Fig. 2C). We refer to this receptor type as: Ode(29–63), or the Pyr-nAChR.

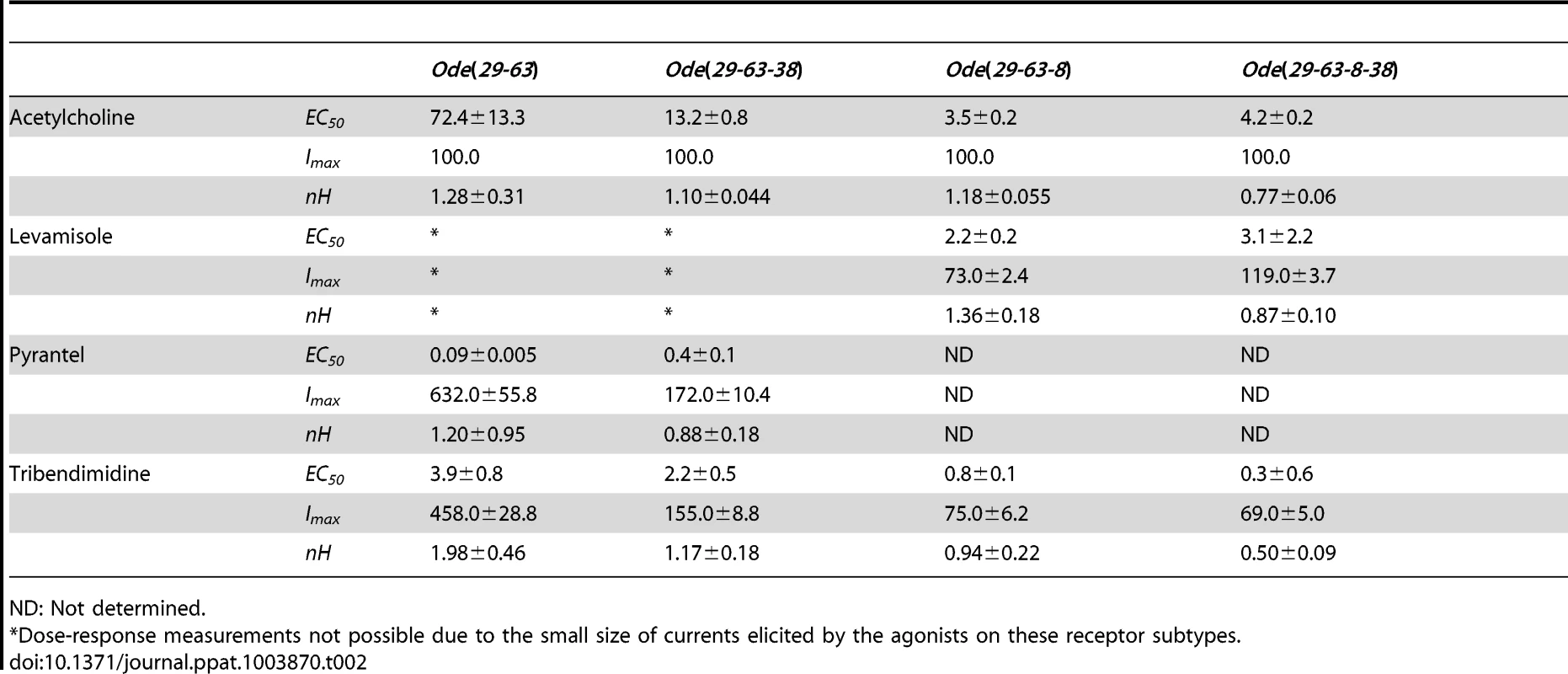

We determined the concentration current-response plot for pyrantel, tribendimidine and acetylcholine, Fig. 2D for Ode(29–63). The EC50 values for pyrantel and tribendimidine were less than the EC50 for acetylcholine but the Imax values were larger for pyrantel and tribendimidine (Table 2). Thus the anthelmintics pyrantel and tribendimidine were much more potent and produced a greater maximum response than the natural ligand, acetylcholine and levamisole on this type of receptor. To date, this result represents the first characterization of a nematode tribendimidine-sensitive nAChR.

Tab. 2. Properties of the four main receptor subtypes obtained from dose-response relationships.

ND: Not determined. We were interested to see if there was evidence of pharmacological changes associated with variation in stoichiometry of the Ode(29-63) receptor. When we injected a 1∶5 ratio of Ode-unc-29∶Ode-unc-63 cRNA with the same 1∶1∶1 ratio of ancillary proteins, the mean amplitudes of the pyrantel and tribendimidine currents were significantly increased (pyrantel: 6-fold increase from a mean of 104 nA to 653 nA, p<0.01; tribendimidine: 7-fold increase from a mean of 68 nA to a mean of 447 nA, p<0.01). The large increase in the size of the currents with increased Ode-unc-63 cRNA suggests that increased UNC-63 favors expression of receptors with a stoichiometry of (UNC-63)3∶ (UNC-29)2 [14]. Also, when we injected 5∶1 Ode-29∶Ode-63 cRNA, the normalized currents of 30 µM nicotine and 100 µM levamisole became significantly bigger than 100 µM acetylcholine (Fig. 2C, E &F) suggesting increased expression of (UNC-63)2∶ (UNC-29)3. The increase in currents with the 1∶5 and 5∶1 Ode-29∶Ode-63 cRNA was not due to variability in currents with different batches of oocytes because we observed the same effects when we injected 1∶1, 1∶5 and 5∶1 Ode-29∶Ode-63 cRNA in the same batch of oocytes.

Expression of Ode(29–63–38), the Pyr/Tbd-nAChR

We subsequently added unc-38 and injected Ode-unc-29∶Ode-unc-63∶Ode-unc-38 cRNAs in the ratio 1∶1∶1, along with the three H. contortus ancillary factors. Oocytes injected with this mix responded with larger currents of around 250 nA to 100 µM acetylcholine and to all the other agonists tested except bephenium and thenium (Fig. 3A–D). Pyrantel was the most potent agonist but with this receptor type, pyrantel and tribendimidine produced the same amplitude of current at 30 µM. We termed this receptor the Ode(29–63–38), or the Pyr/Tbd-nAChR. The potency series of the agonists based on the normalized currents was 30 µM pyrantel ≈30 µM tribendimidine >100 µM acetylcholine >30 µM nicotine ≈100 µM levamisole (Fig. 3 C). The dose-response curves for pyrantel, tribendimidine and acetylcholine are shown in Fig. 3D. The EC50 for pyrantel was less than the EC50 for tribendimidine and acetylcholine (Table 2). The Hill slopes for tribendimidine and acetylcholine were both close to 1.0 (Table 2), showing little co-operativity between agonist concentration and response. Again interestingly, the two anthelmintics, pyrantel and tribendimidine were more potent than the natural ligand and the anthelmintic levamisole, but with this receptor type, the currents were larger than with the Ode(29–63) receptor.

Fig. 3. Voltage-clamp of oocytes injected with different combinations of the four O. dentatum nAChR subunits.

(A) Depiction of a possible arrangement of O. dentatum UNC-29, UNC-63 & UNC-38. ‘X’ represents any of the subunits. PyR, pyrantel; Tbd, tribendimidine, ACh, acetylcholine; Nic, nicotine; Bep, bephenium; The, thenium. (B) Representative traces of inward currents elicited by the various agonists in oocytes injected with 1∶1∶1 Ode-unc-29∶Ode-unc-63∶Ode-unc-38. Pyr & Tbd were the most potent agonists on this receptor subtype. (C) Bar chart (mean ± se) of currents elicited by the different agonists in the Ode-(29 - 38 - 63) Pyr/Tbd-nAChR (paired t-test, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (D) Dose-response of normalized currents vs log concentration for Pyr (inverted Δ, n = 6), Tbd (▴, n = 6) and ACh (•, n = 5) in the Pyr/Tbd-nAChR. (E) Diagrammatic representation of the three subunits, unc-29, unc-63 and acr-8 injected into oocytes. ‘X’ could be any of the three subunits. (F) Representative traces of inward currents produced by the different agonists in oocytes injected with 1∶1∶1 Ode-unc-29∶Ode-unc-63∶Ode-acr-8. (G) Bar chart (mean ± se) of normalized currents elicited by the different agonists in the Ode(29-63-8) receptor subtype. All currents normalized to 100 µM ACh currents; comparisons made with the ACh currents (paired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (H) Dose-response plot of normalized currents vs log. Concentration of Pyr (inverted Δ, n = 6), Tbd (▴, n = 6), ACh (•, n = 6) and Lev (▪, n = 6). (I) Representation of a possible arrangement of the four O. dentatum subunits injected into Xenopus oocytes. (J) Representative traces of inward currents elicited by the different agonists on the Ode(29–63–38–8) or Lev-nAChR. (K) Bar chart (mean ± se) of normalized currents elicited by the different agonists on the Lev-nAChR subtype. Comparisons were made with 100 µM ACh currents, which was used for the normalization (paired t-test, ***p<0.001). (L) Dose-response plot of normalized currents against log of Tbd (▴, n = 6), ACh (•, n = 18) and Lev (○, n = 5) concentrations. Expression of Ode(29–63–8), the ACh-nAChR

When we added Ode-acr-8 and injected Ode-unc-29∶Ode-unc-63∶Ode-acr-8 cRNA in the ratio 1∶1∶1 along with the three H. contortus ancillary factors into the oocytes, we observed even bigger receptor responses to 100 µM acetylcholine. We also observed responses to all the agonists we tested, including bephenium and thenium (Fig. 3E–H), which suggests that Ode-acr-8 introduces bephenium and thenium binding sites. 100 µM acetylcholine produced the largest current responses, always greater than 800 nA and sometimes greater than 1 µA. We termed this receptor type: Ode(29–63–8), or the ACh-nAChR.

For the Ode(29–63–8) receptor, the potency series of the agonists (anthelmintics) based on the normalized currents, was 100 µM acetylcholine >30 µM tribendimidine ≈100 µM levamisole ≈30 µM pyrantel >30 µM nicotine ≈30 µM thenium ≈30 µM bephenium (Fig. 3G). Here, the least potent agonists were nicotine, bephenium and thenium with average currents <20% of the acetylcholine currents. The dose-response curves (Fig. 3H) show that at the highest concentrations tested, levamisole and tribendimidine current responses were less than that of acetylcholine. Despite this, the EC50 values of both tribendimidine and levamisole were lower than acetylcholine on this receptor type. The EC50 values are summarized in Table 2. The levels of co-operativity (slope) were similar for these three agonists, but Imax for acetylcholine (100.0%) was bigger than Imax for tribendimidine (75.0±6.2%) and levamisole (73.0±2.4%).

Two characteristic features of the response of the Ode(29–63–8) receptor to pyrantel suggest the presence of open-channel block which is more pronounced with Ode(29–63–8) than with the other types. Firstly, the maintained application of 30 µM pyrantel produced a response that declined rapidly despite the concentration being maintained, and secondly, on wash-out of pyrantel the response ‘rebounded’ or increased temporally before declining. Pronounced open-channel block with pyrantel has been observed at the single-channel level [30]. Altogether, these results highlight for the first time the reconstitution of a new functional receptor with distinct pharmacological profile made of the UNC-29, UNC-63 and ACR-8 subunits.

Expression of Ode(29–63–8–38), the Lev-nAChR

Finally, we injected all our subunits in a mix of Ode-unc-29∶Ode-unc-63∶Ode-acr-8∶Ode-unc-38 cRNA in the ratio 1∶1∶1∶1 along with the three H. contortus ancillary factors. These subunits reconstituted a receptor type on which 100 µM levamisole produced the biggest responses of >1.5 µA, sometimes reaching >4.5 µA, Fig. 3I–L. We termed this receptor type: Ode(29–63–8–38) or the Lev-nAChR. The potency series of the agonists based on the normalized currents, was 100 µM levamisole >100 µM acetylcholine >30 µM tribendimidine >30 µM thenium ≈30 µM bephenium ≈30 µM pyrantel >30 µM nicotine (Fig. 3K). Here, the least potent agonists were thenium, bephenium, pyrantel and nicotine with average currents <25% of the acetylcholine currents. The EC50 for tribendimidine was less than the EC50 for levamisole and acetylcholine (Table 2). The dose-response curves were rather shallow with Hill slopes less than one for acetylcholine, levamisole and tribendimidine (Table 2). We have shown that expression of Ode-UNC-29, Ode-UNC-63 Ode-ACR-8 and Ode-UNC-38 produced large currents, and that the receptor, Ode(29–63–8–38), was most sensitive to levamisole. It is clear from the observations above that each of the four subunits: Ode-UNC-29, Ode-UNC-63 Ode-ACR-8, and Ode-UNC-38 may combine and be adjacent to different subunits as they form different pentameric nAChRs.

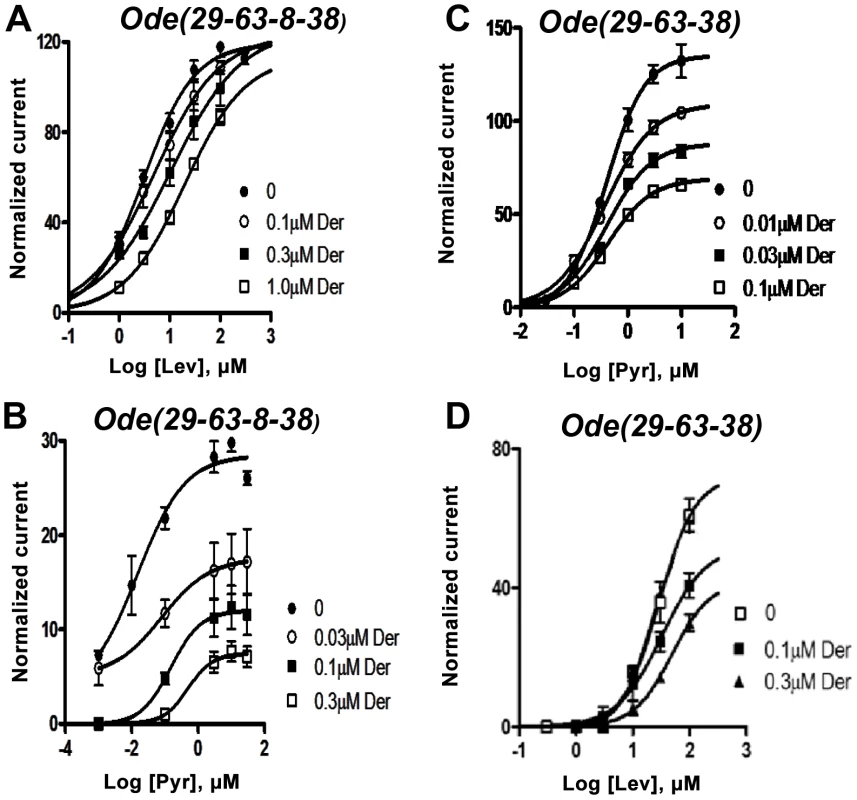

Antagonistic effects of derquantel

We tested the antagonist effects of derquantel on the levamisole and pyrantel concentration-response plots of Ode (29-63-38-8) and Ode (39-63-38), Fig. 4A–D. Recall that levamisole is more potent as an agonist on Ode(29–63–8–38) and pyrantel is more potent on Ode(39-63-38). Fig. 4A shows that derquantel behaves like a potent competitive antagonist of levamisole, with 0.1 µM producing a right shift in EC50 dose-ratio of 1.7 (the antagonist negative log dissociation constant from the Schild equation, pKB, was 6.8±0.1). When we tested the antagonist effects of derquantel on Ode(29–63–8–38) using pyrantel as the agonist, we saw mixed non-competitive and competitive antagonism: there was a right-shift in the EC50 and a reduction to 41% of the maximum response by 0.1 µM derquantel, Fig. 4 B. One explanation for these mixed effects of derquantel is that co-expression of UNC-29, UNC-63, UNC-38, ACR-8 subunits produces a mixture of receptors: mostly Ode(39-63-38-8) receptors that are preferentially activated by levamisole and which are competitively antagonized by derquantel and; a smaller number of receptors like Ode(39-63-38) that are preferentially activated by pyrantel and antagonized non-competitively by derquantel. To test this further we examined the antagonist effects of derquantel on pyrantel and levamisole activation of Ode (39-63-38). Derquantel antagonized both agonists non-competitively, Fig. 4 C & D. We interpret these observations to suggest that expression of Ode(39-63-38-8) receptors can give rise to expression of a smaller number of other receptors including Ode(39-63-38). We comment further on these observations in our discussion. Nonetheless, the competitive and non-competitive antagonism of derquantel when levamisole is used on the two different receptor subtypes, Fig. 4 A & D, illustrates that derquantel effects are subtype selective.

Fig. 4. Effects of derquantel on levamisole-activated and pyrantel-activated expressed Ode(29-63-8-38), the Lev-nAChR, and on pyrantel-activated and levamisole-activated Ode(29-63-38), the PyR/Trbd-nAChR subtypes.

Der: derquantel; Lev: levamisole; Pyr: pyrantel. (A) Antagonistic effects of varying derquantel concentrations on levamisole currents of Ode(29-63-8-38). Levamisole evokes supramaximal normalized currents and derquantel competitively inhibited levamisole currents. (B) Derquantel antagonism of pyrantel currents of Ode(29-63-8-38). Here, derquantel produced mixed non-competitively competitive antagonism. Pyrantel did not activate supramaximal currents. (C) Antagonism of pyrantel by derquantel on the Ode(29-63-38), Pyr/Tbd-nAChR. Derquantel is a potent non-competitive antagonist. (D) Derquantel non-competitively antagonized levamisole responses on the Ode(29-63-38) receptor. The receptor types have different calcium permeabilities

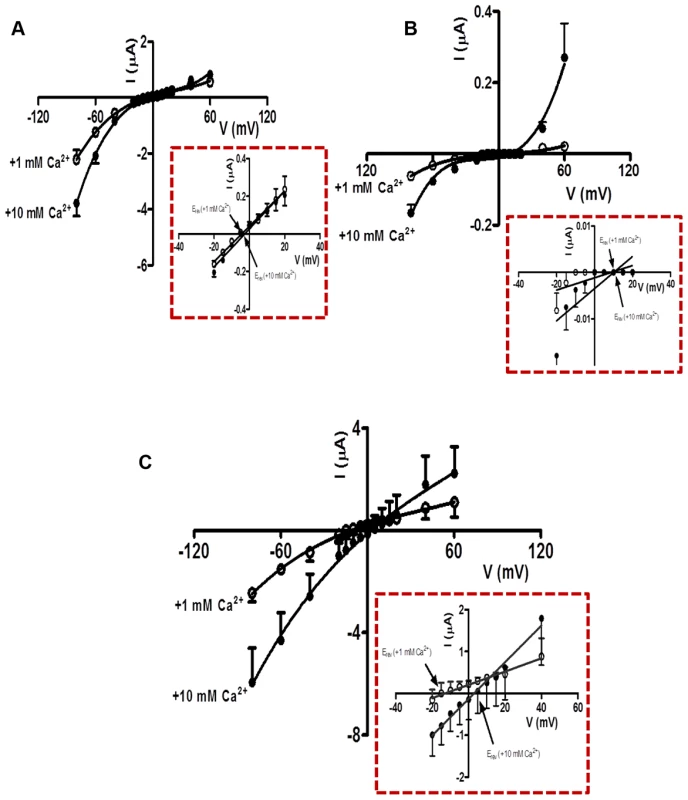

The EC50 concentrations of acetylcholine for the different expressed receptors varied (Table 2), suggesting that there are different physiological functions for the different nAChR types. One physiological difference may be the permeability to the second messenger, calcium. To examine this we measured the relative permeability of calcium in Ode(29–63–38), Ode(29–63–8) and Ode(29–63–8–38), receptors which produced large enough currents to determine reversal potentials.

We observed two different effects of increasing calcium from 1 mM to 10 mM on the acetylcholine currents. One effect was potentiation of the current amplitudes, an effect that was voltage-dependent (Fig. 5A, B & C). The voltage-dependent increases in acetylcholine currents was prominent in Ode(29–63–8–38), and less in the other two receptor types. The potentiating effect of calcium on the acetylcholine currents indicates the presence of positive allosteric binding sites on one or more subunits of the pentameric nAChR [31]. The second effect was a positive shift to the right of the current-voltage plot indicating that the channels are permeable to calcium [32]. A shift in reversal potential of 1.7 mV was recorded for the Ode(29–63–8) (Fig. 5A). Using the Goldman Hodgkin Katz constant field equation (Text S1 Legend), we calculated this change in reversal potential corresponds to a relative calcium permeability ratio, PCa/PNa of 0.5. The reversal potential shift for Ode(29–63–38) was similar, 1.3 mV, also giving a permeability ratio PCa/PNa of 0.4 (Fig. 5B). For Ode(29–63–8–38), the shift was 16.0 mV (Fig. 5C), corresponding to a calcium permeability ratio, PCa/PNa, of 10.3. The Ode(29–63–8–38) receptor, was therefore much more permeable to extracellular calcium and positively allosterically [31] modulated by extracellular calcium than the other two receptor types, a physiologically significant observation.

Fig. 5. Ca2+ permeability of the O. dentatum receptor subtypes with large ACh currents.

(A) Current-Voltage plot for oocytes injected with Ode(29–63–8), showing the change in current with voltage in 1 mM and 10 mM Ca2+ recording solutions. Insert: Magnified view of current-voltage plot from −20 mV to +40 mV showing the Erev in 1 mM and 10 mM extracellular Ca2+. (B) Current-Voltage plot for oocytes injected with Ode(29–63–38) showing the current changes in 1 mM and 10 mM Ca2+ recording solution under different voltages. Insert: Magnified view of current-voltage plot from −20 mV to +40 mV showing the Erev in 1 mM and 10 mM extracellular Ca2+. (C) Current-Voltage plot for oocytes injected with Ode(29–63–38–8) in 1 mM and 10 mM Ca2+ recording solutions. Insert: Magnified view of current-voltage plot from −20 mV to +40 mV showing the Erev in 1 mM and 10 mM extracellular Ca2+. The calcium permeability was calculated using the GHK equation (Text S1 Legend). Ode(29–63–8–38), the Lev-nAChR channels have a mean conductance of 35 pS

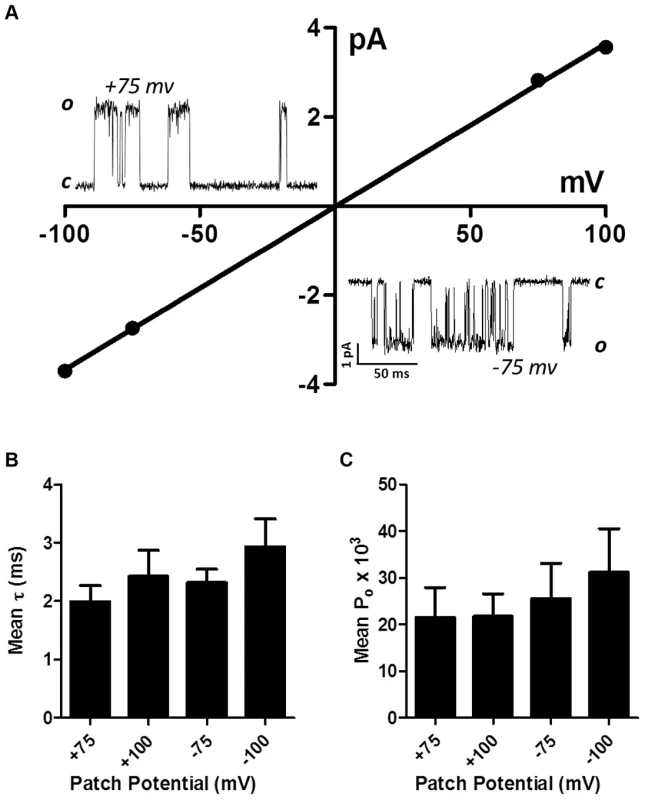

Single-channel studies in Oesophagostomum dentatum body muscle have demonstrated the presence of different nAChR types with conductances of 25, 35, 40 and 45 pS, showing the presence of four or more receptor types. We have shown in experiments here, that combinations of four nAChR subunits from this parasite can produce four pharmacologically different receptor types. We found that the expressed Ode(29–63–38–8) Lev-nAChR type was most sensitive to levamisole and had a high permeability to calcium and hypothesized that this type may be the G35 type. Accordingly we investigated the single-channel properties of this type under patch-clamp using 10 µM levamisole as the agonist. In control oocytes injected with only the ancillary proteins, we recorded no nAChR-like channel currents in 4 oocytes. We found however, that in patches from oocytes expressing the Ode(29–63–8–38) type, that more than 90% of patches contained active, recognizable nAChR channels with one main conductance level. Fig. 6A shows representative channel currents from one of these patches and its current-voltage plots which had a conductance of 36.6±0.5 pS (mean ± SE). The mean conductance of channel from patches made from five different oocytes was 35.1±2.4 pS. We did not test the effects of different cholinergic anthelmintics on channel conductance. The reversal potentials of all plots were close to 0 mV, an indication that the channel was nonselective and permeable to Cs+ (reversal potential of 0 mV).

Fig. 6. Single-channel properties of the Lev-nAChR subtype.

(A) Representative current-voltage plot from oocyte-attached patch with 10 µM levamisole. Inserts are representative channel openings at +75 mV and −75 mV membrane potentials. Even with 10 µM levamisole, we sometimes observed ‘flickering’ channel block events; note the ‘flickering’ channel block shown by openings at −75 mV. (B) Bar chart (mean ± se) of the mean open times (τ) at the different patch potentials. (C) Bar chart (mean ± se) of the probability of channel opening, Po, at the different patch potentials. We measured the mean open times, τ, at the different potentials and observed values of 2.4±0.4 ms at +100 mV and 2.9±0.5 ms at −100 mV (Fig. 6B). The mean open times are comparable to the mean open times recorded in vivo in O. dentatum with the same concentration of levamisole.

The three ancillary proteins affect expression levels

We tested the requirements for the ancillary proteins, RIC-3, UNC-50 and UNC-74, by removing each of the ancillary proteins in turn when expressing the Ode(29–63–8–38) receptor. We found that the requirement for all the ancillary proteins was not essential and that each protein, when absent reduced currents produced by the expressed receptors (Fig. S3). When all the ancillary factors were removed, we observed no measurable currents in response to acetylcholine. Here, we have observed that unlike in C. elegans, robust functional O. dentatum receptors can be reconstituted when one of these three ancillary factors is omitted and that the ancillary proteins can affect the balance of the pharmacology of the receptors expressed (Fig. S3)

Discussion

The origin of diverse nAChR types in parasitic nematodes

We have shown previously in the parasitic nematodes, O. dentatum [24] and A. suum [13], that there are diverse types of nAChR on body muscle of parasitic nematodes which may be activated by cholinergic anthelmintics. In A. suum we found that these types have different sensitivities to different cholinergic anthelmintics like levamisole and derquantel. In O. dentatum there are four types that can be distinguished by their single-channel conductance, with reduced numbers of the G 35 pS type in levamisole resistant isolates. Here we explored and tested the hypothesis that the receptor subtypes may be due to different combinations of subunits. We found that four main pharmacology types could be produced and separated by expressing in Xenopus oocytes different combinations of the α-subunits Ode-UNC-38, Ode-UNC-63 and Ode-ACR-8 together with the non-α subunit Ode-UNC-29. The types could be separated on the basis of their EC50 and amplitude of response to the natural ligand acetylcholine, permeability to calcium and anthelmintic profiles (rank order potency and/or concentration-response relationships). We have not tested the possibility that post-translational modification may serve as an additional mechanism to produce different receptor types.

The different AChR types have different functional properties

Ode(29–63–38–8), Ode(29–63–8) and Ode(29–63–38) produce the largest current responses to acetylcholine. On the basis of the larger size of the currents responses to acetylcholine and the smaller currents of Ode(29–63) mixture, we speculate that the other three receptor types have more important physiological roles in the worm. Ode(29–63–38) was the most sensitive type to acetylcholine with an EC50 of 3.5±0.2 µM but it had a lower calcium permeability, PCa/PNa of 0.5, than Ode(29–63–38–8) that had an acetylcholine EC50 of 4.2±0.2 µM. However, Ode(29–63–38–8) had greater responses to levamisole and a calcium permeability, PCa/PNa of 10.4. Thus the addition of ACR-8 is responsible for increasing the calcium permeability and the response to levamisole. Since the Ode(29–63–38–8) receptor produced the biggest current to levamisole and had a single-channel conductance of 35.1±2.4 pS, close to the in vivo G 35 pS type that is reduced with levamisole resistance, we suggest that Ode(29–63–38–8) subunit combinations give rise to the in vivo G 35 pS channel in O. dentatum. There may also be pH regulatory effects on channel activity of Ode(29–63–38–8). The presence of histidine (pKa 6.0) in the ACR-8 (Fig. S1D, position 282) channel pore entrance on TM2 region is predicted to produce a pH sensitive channel that is less permeable to cations and calcium at pH 6.0 than 7.5. ACR-8 may provide a functional mechanism of reducing depolarization and muscle contraction at low pHs that can occur in an anaerobic environment. It would also have been of interest to look at the single-channel properties of the other receptor types when activated with levamisole to compare with the in vivo channel properties. Unfortunately, the smaller size of the levamisole currents due to the presence of fewer receptors on the oocytes, made single-channel recording less tractable than for Ode(29–63–38–8).

Different nAChR types and sensitivities to levamisole, pyrantel, tribendimine and derquantel

The different nAChR types have different sensitivities to cholinergic anthelmintics: for example Ode(29–63–38–8) produces the biggest response to levamisole, while Ode(29–63–38) produces the biggest response to pyrantel. If these two types of receptors exist together in the nematode parasite, our observations suggest that combinations of levamisole and pyrantel will produce a bigger therapeutic response than either of the two anthelmintics given alone and that combination therapy may be advantageous. However, very few reports of combining levamisole and pyrantel for treatment are available. In one report [33] using T. muris infected mice, combination of levamisole and pyrantel treatment produced antagonism but these authors did not determine the EC50 dose for pyrantel pamoate and used a very high dose of 300 mg/Kg dose, above the normal therapeutic dose. At this level we anticipate the presence of open-channel block limiting the effects of the therapeutic combination [32].

We tested the effects of derquantel on the Ode(29–63–38–8), the Lev-nAChR, and on Ode(29-63-38), the Pyr/Trbd-nAChR. Interestingly, the mode of action of derquantel varied (competitive or non-competitive) with the receptor subtypes when activated by the same agonist, levamisole. The difference in the mode of action will relate to the preferred non-equivalent binding sites of derquantel, of levamisole and of pyrantel on the receptor subtypes. The competitive antagonism of levamisole suggests a common binding site for derquantel on the Ode(29–63–38–8) receptor; the non-competitive antagonism of pyrantel and levamisole by derquantel on Ode(29–63–38) suggests negative allosteric modulation and different non-equivalent binding sites for derquantel and the agonists, levamisole and derquantel, on this receptor. Interestingly the loss of the ACR-8 subunit, which reduces the levamisole sensitivity of the Ode(29-63-38) receptor, changes the antagonism of levamisole from competitive to non-competitive. Thus ACR-8 may contribute to a high affinity binding site of levamisole and a competitive site of derquantel. When ACR-8 was not present derquantel behaved non-competitively. We have interpreted the mixed non-competitive competitive antagonism of pyrantel by derquantel on Ode(29–63–38–8) to be due to a mixed expression of receptor subtypes with mostly the levamisole sensitive Ode(29–63–38–8) receptors being present and a smaller proportion of other receptors like Ode(29-63-38) being present. This is certainly possible because, as we have shown, the subunits can and do combine in different ways to form 4 types of receptor. Although less likely, it may be that: 1) expression of Ode(29-63-38-8) produces only one receptor type, 2) levamisole and pyrantel bind to separate sites on this receptor, 3) derquantel acts competitively, binding at the levamisole site but; 4) derquantel acts as a negative allosteric modulator when pyrantel binds to its receptor. Further study is required to elucidate details of binding sites on the different receptor types. Despite these possibilities we have seen potent antagonist effects of derquantel on both the Ode(29–63–38-8) and the Ode(29–63–38) subtypes suggesting that derquantel could still be active against levamisole resistance associated with reduced ACR-8 expression.

We were also interested in the effects of the novel cholinergic anthelmintics tribendimidine [6] and to compare their effect with the other anthelmintics. We found that tribendimidine was a potent cholinergic anthelmintic on the Ode(29–63–38), Ode(29–63–8) and Ode(29–63–38–8) types. Thus tribendimidine could remain an effective anthelmintic if levamisole resistance in parasites were associated with null mutants or decreased expression of acr-8 and/or unc-38.

Regulation of AChR type expression

The different functional properties of the nAChR types indicate that each type may have different physiological roles to play in the parasite and the proportion of the different types present at the membrane surface is likely to be regulated. This regulation could allow changes in calcium permeability, desensitization, receptor location, receptor number and anthelmintic sensitivity. The control is expected to include dynamic physiological processes and developmental process that take place over different time scales. An adaptable and diverse receptor population may allow changes, even during exposure to cholinergic anthelmintics. We know little about these processes, their time-scales and how they may be involved in anthelmintic resistance in parasitic nematodes but some information is available from C. elegans.

In C. elegans there are a number of genes involved in processing and assembly of the subunits of AChR; specific examples include Cel-ric-3, Cel-unc-74 and Cel-unc-50 [34], [35], [36]. Cel-RIC-3 is a small transmembrane protein, which is a chaperone promoting nAChR folding in the endoplasmic reticulum [37]. The gene Cel-unc-74 encodes a thioredoxin-related protein required for the expression of levamisole AChR subunits [38]. The gene Cel-unc-50 encodes a transmembrane protein in the Golgi apparatus [35]. In Cel-unc-50 mutants, levamisole nAChR subunits are directed to lysosomes for degradation. We found that acetylcholine currents and pharmacological profile of the receptors were sensitive to the presence of the accessory proteins, RIC-3, UNC-74 & UNC-50, suggesting the possibility that the expression level of these proteins could contribute to anthelmintic resistance in parasitic nematodes.

Species differences

We show here that four O. dentatum receptor subunits can be used to reconstitute different functional levamisole receptor types and that levamisole is a full agonist in one of the main types. All of the four main O. dentatum receptor types responded to nicotine, which supports our use of the term nAChR. In contrast, in the expressed levamisole-sensitive AChRs of C. elegans, levamisole is a partial agonist, requires five subunits (Cel-UNC-38:Cel-UNC-29:Cel-UNC-63:Cel-LEV-1:Cel-LEV-8) and does not respond to nicotine. The C. elegans nicotine-sensitive muscle receptor is a separate homopentamer of ACR-16 [39]. We also saw differences between the expressed receptors of O. dentatum and the expressed AChR of H. contortus [16]: only two types of AChRs were produced in Xenopus oocytes expressing H. contortus subunits. Furthermore, we saw differences and similarities between the expressed O. dentatum receptors and the expressed A. suum receptors [14]. Only two subunits were used to reconstitute the A. suum AChR, such that varying the amounts of the subunit cRNAs injected changed the pharmacology of the expressed receptors. This is similar to the Ode(29–63), in that only two subunits were used to reconstitute a Pyr-nAChR and varying the amount of injected subunit cRNAs affected the pharmacology of the receptor. Whereas no ancillary factors were used to reconstitute the A. suum nAChRs, we observed that the three ancillary factors were required to reconstitute the O. dentatum receptors. Another observation is that the amounts of cRNA we injected to reconstitute the O. dentatum receptors were far less than what was injected to reconstitute the A. suum receptors. These demonstrate differences between the expressed receptors of nematodes in the same clade (O. dentatum, C. elegans and H. contortus) and/or in different clades (O. dentatum and A. suum). In addition we have also demonstrated tribendimidine's effect on all four O. dentatum receptor types and in two of the receptor types, the EC50 values show tribendimidine was more potent than the other agonists across the types. We found that pyrantel was the most potent agonist of two types of O. dentatum receptors but it is only most potent in one of the types of H. contortus. The real and significant differences between the effects of pharmacological agents on the model nematode C. elegans and on the parasitic nematode O. dentatum, both Clade V nematodes, shows that species variation requires that effects of anthelmintics on the relevant nematode parasite are tested as a vital reality check.

Materials and Methods

Ethical concerns

All animal care and experimental procedures in this study were in strict accordance with guidelines of good animal practice defined by the Center France-Limousin ethical committee (France). The vertebrate animals (pig) studies were performed under the specific national (French) guidelines set out in the Charte Nationle portant sur l'ethique de l'experimentation animal of the Ministere De Lensiengnement Superieur et de la Recherch and Ministere De L'Agriculture et de la Peche experimental agreement 6623 approved by the Veterinary Services (Direction des Services Vétérinaires) of Indre et Loire (France).

Nematode isolates

These studies were carried out on the levamisole-sensitive (SENS) isolate of O. dentatum as previously described [40]. Large pigs were experimentally infected with 1000 infective larvae (L3s) and infection was monitored 40 days later by fecal egg counts every 3 days. The pigs were slaughtered after 80 days at the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (Nouzilly) abattoir and adult nematodes (males and females) were collected from the large intestine and stored in RNA later (Qiagen®) at −80°C.

Molecular biology

Ten adult males from O. dentatum SENS isolate were used for total RNA preparation using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA synthesis on resuspended and DNase-treated total RNA was carried out with the oligo (dT) RACER primer and superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as previously described [16]. To identify full-length cDNA sequences of O. dentatum unc-29, unc-63 and acr-8 homologues, 5′ - and 3′ - rapid amplification of complementary ends (RACE) polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were performed using the splice leader sequence primer (SL1) with internal reverse primers and internal forward specific primers with reverse transcription 3′-site adapter primers, respectively. PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). Positive identifications were made by BLAST analysis against all Haemonchus contortus entries in the H. contortus information resource data base. Primers designed on unc-29 sequence from H. contortus and C. elegans (unc-29-F0 GGACGAGAAAGATCAAGTTATGCA, unc-29-XR2 TCATCAAATGGGAAGAAYTCGACG) allowed PCR amplification of a 288 bp fragment corresponding to partial O. dentatum unc-29 homologue. New gene specific primer sets were designed on this sequence for the 5′ - and 3′-RACE-PCR providing the full-length cDNA sequence of Ode-unc-29. To identify the unc-63 homologue from O. dentatum, degenerate primers were designed based on the Ode-unc-38 mRNA sequence (accession number GU256648) and the unc-63 and unc-38 sequences of cDNAs available from multiple nematode species (Ode-unc-63-F1 GCGAATCGCGAYGCGAATCGKCT, F2 AARAGYATGTGYCAAATWGAYGT, R3 ATATCCCAYTCGACRCTGGGATA, R4 TAYTTCCAATCYTCRATSACCTG). An 861 bp partial coding sequence of Ode-acr-8 cDNA was amplified using a sense primer (Hco-acr-8-FT1 TATGGTTAGAGATGCAATGGTT) and an antisense primer (Hco-acr-8-RE8 GTGTTTCGATGAAGACAGCTT) from H. contortus Hco-acr-8. The product of this reaction was cloned and sequenced, and the data were used to design primers to get the 5′ and the 3′ ends of the target transcript. To amplify the full-length coding sequence of Ode-unc-38, Ode-unc-63, Ode-unc-29 and Ode-acr-8, we used the Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) and gene specific primer pairs containing HindIII or XhoI and ApaI restriction enzyme sites (Table S1 in Text S1) to facilitate directional cloning into the pTB-207 expression vector that is suitable for in vitro transcription. PCR products were then digested with XhoI and ApaI restriction enzymes (except Ode-unc-29, digested with HindIII and ApaI), purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel), ligated into the respective corresponding sites of the pTB-207 expression vector with T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs), and resulting constructs were transformed into E. coli DG1 cells (Eurogentec) [26]. Three clones of each gene were sequenced using the standard primers T7 and polyT-V. Each of the reported sequences in supplementary figures S1A–D is from one of the nearly identical clones. The mMessage mMachine T7 transcription kit (Ambion) was used for in vitro cRNA synthesis from linearized plasmid DNA templates. The cRNAs were precipitated by lithium chloride, resuspended in RNAse-free water and stored at −80°C.

Sequence analysis and accession numbers

Database searches, prediction of conserved motifs and phylogenetic analyses for the cDNAs were carried out as already described [16]. Maximum likelihood analysis was performed on full-length AChR subunit cDNA sequences as follows: sequences were aligned with Geneious 6.1.6 (Biomatters Ltd) using the translation align MAFFT plugin [41] that aligns the nucleotide sequences as codons based on amino acid sequences. The resulting nucleotide alignment was used to generate phylogenetic trees with the PhyML plugin for Geneious [42]. The HK85 substitution matrix was selected in order to optimize the tree topology and branch lengths. Branch support was evaluated using the chi2 option of PhyML. The accession numbers for cDNA and protein sequences mentioned in this article are C. elegans: UNC-29 NM_059998, UNC-38 NM_059071, UNC-63 NM_059132, ACR-8 JF416644; H. contortus: Hco-unc-29.1 GU060980, Hco-unc-38 GU060984, Hco-unc-63a GU060985, Hco-acr-8 EU006785, Hco-unc-50 HQ116822, Hco-unc-74 HQ116821, Hco-ric-3.1 HQ116823; O. dentatum: Ode-unc-29 JX429919, Ode-unc-38 JX429920, Ode-unc-63 HQ162136, Ode-acr-8 JX429921.

Voltage-clamp studies in oocytes

Xenopus laevis ovaries were obtained from NASCO (Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, USA) and defolliculated using 1–2 mg/ml collagenase type II and Ca2+-free OR2 (mM: NaCl 100, KCl 2.5, HEPES 5, pH 7.5 with NaOH). Alternatively, defolliculated oocytes were purchased from Ecocyte Bioscience (Austin, Texas, USA). Oocytes (animal pole) were microinjected with ∼36 nL of a cRNA injection mix containing 50 ng/µL of each subunit cRNA, as described in [26]. Equal amounts of the H. contortus ancillary factors ric-3, unc-50 and unc-74 were added to each mix. Microinjected oocytes were incubated at 19°C for 2–5 days. The oocytes were incubated in 200 µL of 100 µM BAPTA-AM for ∼3 hours prior to recordings, unless stated otherwise. In control experiments, we recorded from un-injected oocytes. Recording and incubation solutions used are reported in [26]. Incubation solution was supplemented with Na pyruvate 2.5 mM, penicillin 100 U/mL and streptomycin 100 µg/ml. All drugs applied, except tribendimidine and derquantel, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Oocytes were voltage-clamped at −60 mV with an Axoclamp 2B amplifier; all data were acquired on a desktop computer with Clampex 9.2.

Single-channel studies

Oocyte-attached (outside-out) patch-clamp procedure was used to obtain all recordings at room temperature (20°C–25°C). Oocytes were prepared for the recordings by removal of the vitelline membrane with forceps after placing in hypertonic solution, as already described [43]. The oocytes were transferred to the recording chamber and bathed in a high Cs solution with no added Ca2+ (composition in mM: CsCl 140, MgCl2 2, HEPES 10, EGTA 1, pH 7.3) to reduce K+ currents and lower opening of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. Patch electrodes were pulled from thin-walled capillary glass tubing (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT), coated close to the tip with sylgard and fire-polished. The electrodes were filled with a high pipette solution {composition in mM: CsCl 35, CsAc 105, CaCl2 1, HEPES 10} containing 10 µM levamisole. Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) was used to amplify currents which were sampled at 25 kHz with Digidata 1320A (Axon Instruments) and filtered at 1.5 kHz (3-pole Bessel). The linear least squares regression was used to estimate the conductances of the channels since the slopes were linear and did not show rectification.

Data analysis

Acquired data were analyzed with Clampfit 9.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and Graphpad Prism 5.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). The peak of currents in BAPTA-soaked oocytes was measured. The response to 100 µM ACh was normalized to 100% and the responses to the other agonists normalized to that of ACh. For all dose-response relationships, the mean ± s.e of the responses is plotted. Dose-response data points were fitted with the Hill equation as described previously [26]. To calculate the pKB values, the graphs were fitted with the Gaddum/Schild EC50 shift and the bottom of the curves were set to zero.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HotezPJ, BrindleyPJ, BethonyJM, KingCH, PearceEJ, et al. (2008) Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical diseases. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 118 : 1311–1321.

2. HotezPJ, MolyneuxDH, FenwickA, KumaresanJ, SachsSE, et al. (2007) Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases. The New England Journal of Medicine 357 : 1018–1027.

3. BrownLA, JonesAK, BuckinghamSD, MeeCJ, SattelleDB (2006) Contributions from Caenorhabditis elegans functional genetics to antiparasitic drug target identification and validation: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, a case study. International Journal for Parasitology 36 : 617–624.

4. WolstenholmeAJ, FairweatherI, PrichardR, von Samson-HimmelstjernaG, SangsterNC (2004) Drug resistance in veterinary helminths. Trends in Parasitology 20 (10) 469–476.

5. MartinRJ, RobertsonAP (2007) Mode of action of Levamisole and pyrantel, anthelmintic resistance, E153 and Q57. Parasitology 134 : 1093–1104.

6. XiaoS, Hui-MingW, TannerM, UtzingerJ, ChongW (2005) Tribendimidine: a promising, safe and broad-spectrum anthelmintic agent from China. Acta Trop 94 (1) 1–14.

7. KaminskyR, GauvryN, Schorderet WeberS, SkripskyT, BouvierJ, et al. (2008) Identification of the amino-acetonitrile derivative monepantel (AAD 1566) as a new anthelmintic drug development candidate. Parasitol Res 103 (4) 931–939.

8. KaminskyR, DucrayP, JungM, CloverR, RufenerL, et al. (2008) A new class of anthelmintics effective against drug-resistant nematodes. Nature 452 : 176–180.

9. RobertsonAP, ClarkCL, BurnsTA, ThompsonDP, GearyTG, et al. (2002) Paraherquamide and 2-Deoxy-paraherquamide Distinguish Cholinergic Receptor Subtypes in Ascaris suum. The Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics 302 : 853–860.

10. XiaoS-H, UtzingerJ, TannerM, KeiserJ, XueJ (2013) Advances with the Chinese anthelmintic drug tribendimidine in clinical trials and laboratory investigations. Acta Trop 126 (2) 115–126.

11. HuY, XiaoS-H, AroianRV (2009) The new anthelmintic tribendimidine is an L-type (Levamisole and Pyrantel) nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3 (8) e499.

12. LeeB, ClothierM, DuttonF, NelsonS, JohnsonS, et al. (2002) Marcfortine and paraherquamide class of anthelmintics: discovery of PNU-141962. Curr Top Med Chem 2 (7) 779–793.

13. QianH, MartinRJ, RobertsonAP (2006) Pharmacology of N-, L-, and B-subtypes of nematode nAChR resolved at the single-channel level in Ascaris suum. The FASEB Journal 20: E2108–E2116.

14. WilliamsonSM, RobertsonAP, BrownL, WilliamsT, WoodsDJ, et al. (2009) The Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors of the Parasitic Nematode Ascaris suum: Formation of Two Distinct Drug Targets by Varying the Relative Expression Levels of Two Subunits. PloS PATHOGENS 5: e1000517.

15. NeveuC, CharvetCL, FauvinA, CortetJ, BeechRN, et al. (2010) Genetic diversity of levamisole receptor subunits in parasitic nematode species and abbreviated transcripts associated with resistance. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 20 : 414–425.

16. BoulinT, FauvinA, CharvetCL, CortetJ, CabaretJ, et al. (2011) Functional reconstitution of Haemonchus contortus acetylcholine receptors in Xenopus oocytes provides mechanistic insights into levamisole resistance. Br J Pharmacol 164 : 1421–1432.

17. MartinRJ (1997) Modes of action of anthelmintic drugs. Veterinary Journal 154 : 11–34.

18. RichmondJE, JorgensenEM (1999) One GABA and two acetylcholine receptors function at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. Nature Neuroscience 2 : 791–797.

19. CulettoE, BaylisHA, RichmondJE, JonesAK, FlemingJT, et al. (2004) The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-63 Gene Encodes a Levamisole-sensitive Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor alpha Subunit. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 : 42476–42483.

20. FlemingJT, SquireMD, BarnesTM, TornoeC, MatsudaK, et al. (1997) Caenorhabditis elegans levamisole resistance genes lev-1, unc-29 and unc-38 encode functional nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits. J Neurosci 17 : 5843–5857.

21. TowersPR, EdwardsB, RichmondJE, SattelleDB (2005) The Caenorhabditis elegans lev-8 gene encodes a novel type of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit. J Neurochem 93 : 1–9.

22. LewisJA, WuC-H, BergH, LevineJH (1980) The genetics of levamisole resistance in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuroscience 5 : 967–989.

23. TouroutineD, FoxR, Von StetinaS, AB, MillerDr, et al. (2005) ACR-16 encodes an essential subunit of the levamisole-resistant nicotinic receptor at the Caenorhabditis elegans neuromuscular junction. J Biol Chem 280 (29) 27013–27021.

24. RobertsonAP, BjornHE, MartinRJ (1999) Resistance to levamisole resolved at the single-channel level. The FASEB Journal 13 : 749–760.

25. RobertsonAP, BjornHE, MartinRJ (2000) Pyrantel resistance alters nematode nicotinic acetylcholine receptor single-channel properties. European Journal of Pharmacology 394 : 1–8.

26. BoulinT, GielenM, RichmondJE, WilliamsDC, PaolettiP, et al. (2008) Eight genes are required for functional reconstitution of the Caenorhabditis elegans levamisole-sensitive acetylcholine receptor. PNAS 105 : 18590–18595.

27. QianH, RobertsonAP, Powell-CoffmanJ, MartinRJ (2008) Levamisole resistance resolved at the single-channel level in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J 22 : 3247–3254.

28. JonesAK, DavisP, HodgkinJ, SattelleDB (2007) The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene family of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: an update on nomenclature. Invert Neurosci 7 (2) 129–131.

29. BlaxterML, De LeyP, GareyJ, LiuL, ScheldemanP, et al. (1998) A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature 392 (6671) 71–75.

30. RobertsonSJ, PenningtonAJ, EvansAM, MartinRJ (1994) The action of pyrantel as an agonist and an open channel blocker at acetylcholine receptors in isolated Ascaris suum muscle vesicles. Eur J Pharmacol 271 (2–3) 273–282.

31. ChangY, HuangY, WhiteakerP (2010) Mechanism of allosteric modulation of the cys-loop receptors. Pharmaceuticals 3 : 2592–2609.

32. VerninoS, AmadorM, LuetjeCW, PatrickJ, DaniJA (1992) Calcium modulation and high calcium permeability of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron 8 : 127–134.

33. KeiserJ, TrittenL, AdelfioR, vargasM (2012) Effect of combinations of marketed human anthelmintic drugs against Trichuris muris in vitro and in vivo. Parasites & Vectors 5 : 292.

34. AlmedomRB, LiewaldJF, HernandoG, SchultheisC, RayesD, et al. (2009) An ER-resident membrane protein complex regulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit composition at the synapse. EMBO J 28 : 2636–2649.

35. EimerS, GottschalkA, HengartnerM, HorvitzHR, RichmondJ, et al. (2007) Regulation of nicotinic receptor trafficking by the transmembrane Golgi protein UNC-50. EMBO J 26 : 4313–4323.

36. GottschalkA, AlmedomRB, SchedletzkyT, AndersonSD, YatesJRIII, et al. (2005) Identification and characterization of novel nicotinic receptor-associated proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J 24 : 2566–2578.

37. HaleviS, McKayJ, PalfreymanM, YassinL, EshelM, et al. (2002) The C. elegans ric-3 gene is required for maturation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. EMBO J 21 : 1012–1020.

38. HaugstetterJ, BlicherT, EllgaardL (2005) Identification and characterization of a novel thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 280 : 8371–8380.

39. TouroutineD, FoxRM, Von StetinaSE, BurdinaA, MillerDMIII, et al. (2005) ACR-16 encodes an essential subunit of the levamisole-resistant nicotinic receptor at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. J Biol Chem 280 (29) 27013–27021.

40. VaradyM, BjornH, CravenJ, NansenP (1997) In vitro characterization of lines of Oesophagostomum dentatum selected or not selected for resistance to pyrantel, levamisole and ivermectin. International Journal for Parasitology 27 : 77–81.

41. KatohK, MisawaK, KumaK, MiyataT (2002) MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res 30 : 3059–3066.

42. GuindonS, GascuelO (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52 : 696–704.

43. BrownLA, JohnsonBA, GoodmanMB (2008) Patch clamp recording of ion channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Vis Exp 20: e936 910.3791/3936.

44. EdgarRC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32 : 1792–1797.

45. ImotoK, BuschC, SakmannB, MishinaM, KonnoT, et al. (1988) Rings of negatively charged amino acids determine the acetylcholine receptor channel conductance. Nature 335 (13) 645–648.

46. ImotoK, MethfesselC, SakmannB, MishinaM, MoriY, et al. (1986) Location of a δ-subunit region determining ion transport through the acetylcholine receptor channel. Nature 324 (6098) 670–674.

47. EdgarR (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32 : 1792–1797.

48. SaitouN, NeiM (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4 : 406–425.

49. Ben-AmiHC, BialaY, FarahH, ElishevitzE, BattatE, et al. (2009) Receptor and subunit specific interactions of RIC-3 with Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Biochemistry 48 : 12329–12336.

50. MillarNS (2008) RIC-3: a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor chaperone. British Journal of Pharmacology 153: S177–S183.

51. LansdellSJ, GeeVJ, HarknessPC, DowardAI, BakerER, et al. (2005) RIC-3 enhances functional expressioin of multiple nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in mammalian cells. Mol Pharmacol 68 : 1431–1438.

52. Ben-AmiHC, YassinL, FarahH, MichaeliA, EshelM, et al. (2005) RIC-3 affects properties and quantity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors via a mechanism that does not require the coiled-coil domains. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 : 28053–28060.

53. EimerS, GottschalkA, HengartnerM, HorvitzHR, RichmondJ, et al. (2007) Regulation of nicotinic receptor trafficking by the transmembrane Golgi protein UNC-50. EMBO J 26 : 4313–4323.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Serotonin Signaling in : A Serotonin–Activated G Protein-Coupled Receptor Controls Parasite MovementČlánek Regulators of Cell Cycle Progression and Differentiation Identified Using a Kinome-Wide RNAi ScreenČlánek IFNγ/IL-10 Co-producing Cells Dominate the CD4 Response to Malaria in Highly Exposed ChildrenČlánek Functions of CPSF6 for HIV-1 as Revealed by HIV-1 Capsid Evolution in HLA-B27-Positive SubjectsČlánek Decreases in Colonic and Systemic Inflammation in Chronic HIV Infection after IL-7 Administration

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 1- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- HIV-1 Accessory Proteins Adapt Cellular Adaptors to Facilitate Immune Evasion

- Ranaviruses: Not Just for Frogs

- Effectors and Effector Delivery in

- Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Dynamics Tune Interferon-Alfa Production in SIV-Infected Cynomolgus Macaques

- Lu/BCAM Adhesion Glycoprotein Is a Receptor for Cytotoxic Necrotizing Factor 1 (CNF1)

- A Substrate-Fusion Protein Is Trapped inside the Type III Secretion System Channel in

- Parvovirus-Induced Depletion of Cyclin B1 Prevents Mitotic Entry of Infected Cells

- Red Blood Cell Invasion by : Structural Basis for DBP Engagement of DARC

- NsrR, GadE, and GadX Interplay in Repressing Expression of the O157:H7 LEE Pathogenicity Island in Response to Nitric Oxide

- Loss of Circulating CD4 T Cells with B Cell Helper Function during Chronic HIV Infection

- TREM-1 Deficiency Can Attenuate Disease Severity without Affecting Pathogen Clearance

- Origin, Migration Routes and Worldwide Population Genetic Structure of the Wheat Yellow Rust Pathogen f.sp.

- Glutamate Utilization Couples Oxidative Stress Defense and the Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle in Phagosomal Escape

- Serotonin Signaling in : A Serotonin–Activated G Protein-Coupled Receptor Controls Parasite Movement

- Recovery of an Antiviral Antibody Response following Attrition Caused by Unrelated Infection

- Regulators of Cell Cycle Progression and Differentiation Identified Using a Kinome-Wide RNAi Screen

- Absence of Intestinal PPARγ Aggravates Acute Infectious Colitis in Mice through a Lipocalin-2–Dependent Pathway

- Induction of a Stringent Metabolic Response in Intracellular Stages of Leads to Increased Dependence on Mitochondrial Metabolism

- CTCF and Rad21 Act as Host Cell Restriction Factors for Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus (KSHV) Lytic Replication by Modulating Viral Gene Transcription

- Gammaherpesviral Gene Expression and Virion Composition Are Broadly Controlled by Accelerated mRNA Degradation

- The Arabidopsis Silencing Pathway Modulates PAMP- and Effector-Triggered Immunity through the Post-transcriptional Control of Disease Resistance Genes

- Inflammatory Stimuli Reprogram Macrophage Phagocytosis to Macropinocytosis for the Rapid Elimination of Pathogens

- Alphavirus Mutator Variants Present Host-Specific Defects and Attenuation in Mammalian and Insect Models

- Phosphopyruvate Carboxylase Identified as a Key Enzyme in Erythrocytic Carbon Metabolism

- IFNγ/IL-10 Co-producing Cells Dominate the CD4 Response to Malaria in Highly Exposed Children

- Electron Tomography of HIV-1 Infection in Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue

- Characterisation of a Multi-ligand Binding Chemoreceptor CcmL (Tlp3) of

- Single Cell Stochastic Regulation of Pilus Phase Variation by an Attenuation-like Mechanism

- Cell Tropism Predicts Long-term Nucleotide Substitution Rates of Mammalian RNA Viruses

- Functions of CPSF6 for HIV-1 as Revealed by HIV-1 Capsid Evolution in HLA-B27-Positive Subjects

- RNA-seq Analysis of Host and Viral Gene Expression Highlights Interaction between Varicella Zoster Virus and Keratinocyte Differentiation

- Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated Herpesvirus Tegument Protein ORF75 Is Essential for Viral Lytic Replication and Plays a Critical Role in the Antagonization of ND10-Instituted Intrinsic Immunity

- DAMP Molecule S100A9 Acts as a Molecular Pattern to Enhance Inflammation during Influenza A Virus Infection: Role of DDX21-TRIF-TLR4-MyD88 Pathway

- Variable Suites of Non-effector Genes Are Co-regulated in the Type III Secretion Virulence Regulon across the Phylogeny

- Reengineering Redox Sensitive GFP to Measure Mycothiol Redox Potential of during Infection

- Preservation of Tetherin and CD4 Counter-Activities in Circulating Alleles despite Extensive Sequence Variation within HIV-1 Infected Individuals

- KSHV 2.0: A Comprehensive Annotation of the Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Genome Using Next-Generation Sequencing Reveals Novel Genomic and Functional Features

- Nutrient Limitation Governs Metabolism and Niche Adaptation in the Human Nose

- Decreases in Colonic and Systemic Inflammation in Chronic HIV Infection after IL-7 Administration

- Investigation of Acetylcholine Receptor Diversity in a Nematode Parasite Leads to Characterization of Tribendimidine- and Derquantel-Sensitive nAChRs

- Intranasal Vaccination Promotes Detrimental Th17-Mediated Immunity against Influenza Infection

- -Mediated Inhibition of Iron Export Promotes Parasite Replication in Macrophages

- Variation in RNA Virus Mutation Rates across Host Cells

- A Single Amino Acid in the Stalk Region of the H1N1pdm Influenza Virus HA Protein Affects Viral Fusion, Stability and Infectivity

- Group B Engages an Inhibitory Siglec through Sialic Acid Mimicry to Blunt Innate Immune and Inflammatory Responses

- Synthesis and Biological Properties of Fungal Glucosylceramide

- HIV Protective KIR3DL1/S1-HLA-B Genotypes Influence NK Cell-Mediated Inhibition of HIV Replication in Autologous CD4 Targets

- Recruitment of PfSET2 by RNA Polymerase II to Variant Antigen Encoding Loci Contributes to Antigenic Variation in

- Human and Plant Fungal Pathogens: The Role of Secondary Metabolites

- Lyme Disease: Call for a “Manhattan Project” to Combat the Epidemic

- Enhancing Virus-Specific Immunity by Combining Therapeutic Vaccination and PD-L1 Blockade in Chronic Hepadnaviral Infection

- Suppression of Interferon Lambda Signaling by SOCS-1 Results in Their Excessive Production during Influenza Virus Infection

- Inflammation Fuels Colicin Ib-Dependent Competition of Serovar Typhimurium and in Blooms

- Host-Specific Enzyme-Substrate Interactions in SPM-1 Metallo-β-Lactamase Are Modulated by Second Sphere Residues

- STING-Dependent Type I IFN Production Inhibits Cell-Mediated Immunity to

- From Scourge to Cure: Tumour-Selective Viral Pathogenesis as a New Strategy against Cancer

- Lysine Acetyltransferase GCN5b Interacts with AP2 Factors and Is Required for Proliferation

- Narrow Bottlenecks Affect Populations during Vertical Seed Transmission but not during Leaf Colonization

- Targeted Cytotoxic Therapy Kills Persisting HIV Infected Cells During ART

- Murine Gammaherpesvirus M2 Protein Induction of IRF4 via the NFAT Pathway Leads to IL-10 Expression in B Cells

- iNKT Cell Production of GM-CSF Controls

- Malaria-Induced NLRP12/NLRP3-Dependent Caspase-1 Activation Mediates Inflammation and Hypersensitivity to Bacterial Superinfection

- Detection of Host-Derived Sphingosine by Is Important for Survival in the Murine Lung

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Lyme Disease: Call for a “Manhattan Project” to Combat the Epidemic

- Origin, Migration Routes and Worldwide Population Genetic Structure of the Wheat Yellow Rust Pathogen f.sp.

- IFNγ/IL-10 Co-producing Cells Dominate the CD4 Response to Malaria in Highly Exposed Children

- Human and Plant Fungal Pathogens: The Role of Secondary Metabolites

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání